The Social-Network Effect That Is Helping Legalize Gay Marriage

How peer-to-peer networking tool Amicus helped activists in Minnesota and Washington win same-sex-marriage campaigns

It was no secret during past decades of ballot-box pummeling that social connections help determine where people stand on LGBT rights, say the organizers behind November 6's same-sex marriage wins in Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, and Washington. They knew the public-opinion polls. Simply having a gay family member, friend, or colleague doubles the likelihood of support.

"The meta narrative," says Michael Cole-Schwartz, director of media efforts for the Human Rights Campaign, "is that we win these fights because Americans know that LGBT people are their neighbors, their cousins, their aunts and uncles, the people they sit next to in church, and the people they shop with at the grocery store." More than that, experience told them that personal conversations on or around the significance of marriage were especially persuasive. And that stayed true when those talks happened between straight people, like the conversations with his daughters Sasha and Malia that were said to change President Obama's thinking.

But there was still a conundrum, and it had to do with amplification, explains Cole-Schwartz: "How do we get these conversations that happen naturally to happen more often?" It's a political challenge not limited to the question of LGBT issues. In their groundbreaking 2004 book Get Out the Vote!, Yale political scientists Alan S. Gerber and Donald P. Green wrote that "the more personal the interaction, the harder it is to reproduce on a large scale."

At the time, though, Facebook had barely emerged from its Harvard dorm. Eight years later, Human Rights Campaign and local coalitions like Washington United for Marriage and Minnesotans United for All Families say they're beginning to figure out is how to tap the billions of social connections that have emerged there over the last four election cycles. HRC and its allies used a tool called Amicus, a product of the New York tech scene that puts your "social graph" -- a term popularized by Mark Zuckerberg to refer to the available digital knowledge on how all of us are related -- to work in raising political awareness, asking for votes, and raising money (the tool's name, of course, comes from the Latin for "friend").

Here's how it works. Pull up Call4Equality.HRC.org, that organization's version of Amicus, and then sign onto Facebook. First, you identify yourself in the voter file from public records. After that, up pops a listing of your Facebook friends, their identities fleshed out with the data Amicus has collected about them: When they were born. Where they were born. Where they live now. Where they went to high school. Where they went to college. On the nuts-and-bolts level, it's just data matching. But the social effect is powerful. The cause now knows not only a ton about a potential new supporter but also how they fit into a current supporter's own little piece of humanity's web.

Activists say they're beginning to figure out is how to tap the billions of social connections that have emerged there over the last four election cycles.

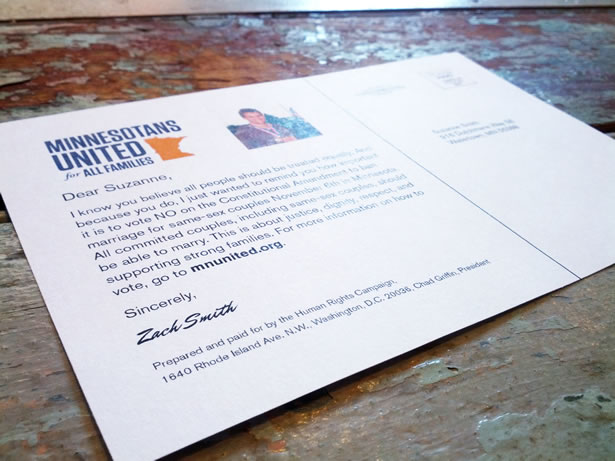

Then the organizers put that power to work. You are asked to reach out and contact those friends and friends-of-friends. The gold standard of outreach is to call them on the phone. (Suggested language: "You got married because you were in love and wanted to start a family? Me too.") But you can opt to email them instead. You can even send them an actual printed postcard, personalized with your photo from Facebook. That combination of public and semi-public data can be startling, but it works, says Seth Bannon, co-founder and CEO of Amicus. People are twice as likely to do something political if, through Amicus, they're asked by a friend to do it, he says.

"You couldn't have done this five years ago," Bannon says. "Bits and pieces of it weren't possible even a few months ago." In large part, that's because Facebook has spent the last few years steadily opening its social graph to outside developers, and the voter data being matched with the graph comes from Catalist, the progressive information outfit that's only a few years old itself. Together the tool equipped marriage-vote organizers to operationalize their accumulated wisdom about human behavior in this election.

One striking revelation from Facebook, say the LGBT-vote organizers, is that Americans are connected far and wide, even when they might not know that they are. Let's say you live in Florida or New Jersey and don't want to see Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, or Washington come down against same-sex marriage. You might have a college dormmate, cousin's best friend, or colleague from three jobs ago now living in Bangor or Glen Echo or Minneapolis or Richland. You might not remember that, but Facebook does. A pair of relevant statistics: The median "friend" count on Facebook is 190, while in "real life" Americans report having an average of two close friends. (There is, for the record, an opportunity to pull folks who aren't on Facebook into the mix using Amicus's find-a-friend feature.) That allows the HRC to target their million-and-a-half-member supporter base to whatever political geography is relevant to the battle of the moment. "It gives us a universe of persuadable people for the cohort already on our side to reach out to" says Cole-Schwartz.

Six years later, an explosion in their New Haven duplex on election night (of all nights) left Bannon's mother with lasting injuries that made engaging in politics difficult. "I realized that there were millions of people who couldn't do anything about it," Bannon says. "I dedicated myself to being their proxies." In the years since, Bannon has churned through campaigns, taking a leave of absence from Harvard in 2006 for Ned Lamont's bid to unseat Lieberman, and putting in time for Obama in 2008 and Alan Khazei's Senate campaign in 2009. Along the way, he says, "I was always frustrated with the tech." Bad systems meant wasting the efforts of volunteers, what he calls one of the more "beautiful" parts of the campaign life. He's set himself on building a solution.

But Amicus is still in its early stages. On raw numbers, "it wasn't a barnstormer" at roll-out says James Servino, an online organizer with HRC. Amicus loses a lot of potential allies who come over the transom and don't engage right away, Bannon concedes, adding that increasing the platform's stickiness tops their to-do list. Organizers say that they would have liked to have seen more people pick up the phone. HRC puts the number of direct calls through Amicus at 7,000; the vote in Washington State was won by 228,000 votes. But organizers see in this early deployment signs of success.

Funders, too, see a lot to like in Amicus. A week after the election, the company announced it had completed a round of funding worth $3.2 million. Amicus, says Bannon, is looking to increase its staff of seven, adding a data scientist as soon as possible. It would be ideal to have someone schooled in sociology, too, who might help them figure out not only who should be asked to engage in political action, but the best person in their social graph to prod them to make that leap. (Amicus is non-partisan and the platform generally open, "but if you're trying to take away rights," says Bannon, "we won't work with you.") The company is also considering taking more seriously something in which they've only been dabbling: anonymous modeling. "If you call a 32-year-old woman at 3 p.m. on a Thursday and ask her for $30 and she says 'no,'" says Bannon, "we capture that." It's valuable data that gets poured into a growing cache that could someday allow them to know that a woman of that age and job status should be called after working hours and asked for 20 bucks instead.

Also important: the psychology of volunteers themselves. The vision driving Amicus is one of creating a more robust version of the campaign experience -- more immediate, more knowing. But some things are lost in the digital conversion, like the the camaraderie that nudges volunteers towards picking up the phone at an in-person phone bank. To help solve that, volunteers who rack up participation points and thus moved up levels were rewarded with both virtual goods, like Facebook badges, and real goods, like stickers, T-shirts, and drawstring bags.

The gamification proved serious business. "People were willing to write an angry email when they didn't get their points," says Bannon, "which is a pretty good sign it works." They have been talking to Gerber, the political scientist, about adding in subtle encouragements like, perhaps, bumping an old buddy to the top of a volunteers call list after a few discouraging interactions with voters closer to the edges of their networks. And there are also more obvious affirmations on deck. As part of a planned redesign, says Bannon, "it's going to tell you when someone has just been hung up on five times in a row and needs a high five." (A virtual one, of course.)

"People were willing to write an angry email when they didn't get their points," says Bannon, "which is a pretty good sign it works."

Amicus fits comfortably into a bigger, counterintuitive trend in digital politics. In a recent post-campaign debrief, Obama campaign manager Jim Messina argued that "what campaigns are evolving into, actually, in many ways is a return to the past." Much of the advanced tech the campaign deployed, said Messina, succeeded in making the experience of door-to-door campaigning less tedious and more efficient. The ambition of a surprising amount of political technologies is to move away from the cacophony of political TV ads and tweets and Facebook wall posts -- and back to actual conversations between actual humans. Amicus connects users via social media but discourages its use in practice; political tweets and posts, says Bannon, come across as too "spammy."

Of course, this is a new kind of conversation where you have far more knowledge about your neighbor at your fingertips than you did before. Is that creepy? Is it too creepy? Logging onto Amicus and seeing even just your own name in the voter file can be unsettling. Public information is one thing, but this is public public, combined with all that social-media data that wasn't meant to mean anything. Bannon admits there is often a "whoa" moment. You pick up the phone, dial the number on the voter file, and say, "Hey, you went to college with my step-brother, and we hung out that one time at the Brickskeller your junior year. How do you feel about marriage equality?" In some ways, Amicus engineers around it, pretending to know less than it does by, for example, hiding street numbers. But organizers say they're riding a technological wave where people seem to get over their squeamishness if they judge that they're trading privacy for the chance to make a stronger social connection.

Right now, Amicus is calibrated to make the most of even the squeamish. There are low-bar asks that still manage to be powerful. The first thing Amicus users are asked to do is act as a data refiner, matching their Facebook list to their friend's correct entry in the voter file. (People's names aren't unique, of course, and it's not always clear which address is a current one.) Bannon says that 21,000 matches were made through the HRC, and about as many in Minnesota. "If someone matches friends and leaves because they're shy, they're still creating a lot of value," says Bannon. "They're enabling another volunteer to make that friend-of-a-friend call." What's more, Minnesota volunteers were also asked to tag their friends as supporters or opponents of same-sex marriage. As for who owns the resulting data, the information on whose Facebook profile matches which entry in the voter file stays with Amicus. The cause -- say, Minnesota United -- gets to keep that insight on whether or not someone is a same-sex marriage supporter.

It's a kind of in-kind contribution of your social graph, and a valuable one. "Once we let people know that it saves us time and money to let us know that your friends are voting 'no,' it's pretty convincing," says Nicholas Kor, who worked on Minnesota United's "Let Your Friends kNOw" program. In Minnesota, they assign numbers to it. A few clicks to let them know where a friend stands, the Minnesota coalition told volunteers, saved the marriage push half an hour's worth of work and about $30.

Amicus is still a fledgling technology, but the ideas on peer-to-peer organizing it's tapping into run through the age of data-infused politics. In Facebook's own early days, users were given the choice of tagging themselves with a discrete number of political identifiers ranging from very liberal to very conservative, with apathetic also included in the mix. The caused a stir when, in 2008, they switched instead to a scrolling mix of international political parties. Today, the "political affiliation" option is a jumble of adjectives and established organizations, as well as a text box for people to fill in however they wish. The acknowledgement: when you move beyond simply Republican and Democrat in America, things get messy. The Obama campaign realized that many of the voters they'd identified as possibly swinging their way watch Fox News, deputy campaign manager Stephanie Cutter said at a recent panel. On the same-sex-marriage question, state-level organizers say, you can study the data enough to know that Democrats tend to be more supportive of same-sex marriage than Republicans, women more than men, urban voters more than rural ones. But those models are rough and incomplete.

"It's not a clean partisan break," says Zach Silk, the 30-something campaign manager for Washington's same-sex-marriage campaign. The final vote breakdowns aren't in, and the state's voter records are non-partisan, but Silk explains, "we found that there were a pretty remarkable number of conservative voters that ended up supporting us." Social data, he says, helped narrow down a universe of some 3.6 million voters to figure out which of them were the few, important persuadable ones. It was a tactic borne of necessity. "We know that as much as 20 percent of Democrats weren't going to be with us," says Silk. "To get a winning majority, we needed to bring in as many libertarian-oriented Republicans as possible." It was a pattern repeated across the four battleground states.

Ari Wallach, the strategist known as one of the minds behind such work as Samuel L. Jackson's pro-Obama "Wake the F___ Up" video, Sarah Silverman's profane voter ID ads, and 2008's The Great Schlep, helped launch Friendfactor, a celebrity-celebrated political effort to make the most of the social bonds between Americans of all sexual identities.

One lesson he's picked up, Wallach says, is that "20- and 30-year-olds don't want to take political action on behalf of organizations anymore. Their brand allegiance has shifted from vertical, broadcast brands to hyperlocal" -- friends, co-workers, neighbors. Amicus makes peer-to-peer connections possible on that level, and not only is the tool not branded as Amicus when volunteers are using it, it's sometimes not even branded with the name of the organization that's providing supporters with an organizing channel. In Washington, Amicus and other tools were simply packaged as Marriage Hero. "I see in Amicus the future of political parties, more than I see the future of political parties at the DNC or the RNC," Wallach says. Maybe, maybe not, but it's not difficult to imagine that institutions now framed around partisan dichotomies might be reshaped with fuller knowledge of the likes, interests, and friendships of the American electorate.

Our politics, as practiced by real-live humans, is rarely quite as clean as our partisanship suggests. Lowell Weicker ended up ending his career as an independent. For that matter, so did Joe Lieberman. People are complicated. Just ask their friends.