Antarctic ice floes extended further than ever recorded this southern winter, confounding the world’s most-trusted climate models.

“It’s not expected,” says Professor John Turner, a climate expert at the British Antarctic Survey. “The world’s best 50 models were run and 95% of them have Antarctic sea ice decreasing over the past 30 years.”

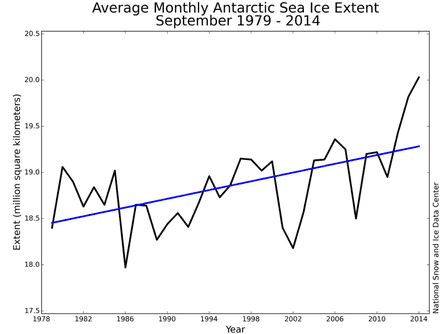

The winter ice around the southern continent has been growing relatively constantly since records began in 1979. The US National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC), which monitors sea ice using satellite data, said this week that the year’s maximum was 1.54m sq km (595,000 sq miles) above the 1981-2010 average. The past three winters have all produced record levels of ice.

This contrasts sharply with the continuing decline of sea ice in the Arctic, which again recorded below average levels of ice during the summer. The 10 lowest recorded sea ice minimums – i.e. the lowest extent of sea ice in the summer – have all occurred in the past 10 years. This decline is consistent with climate models, every one of which predicts that continued man-made greenhouse gas emissions will eventually cause Arctic summer ice to disappear completely.

But Dr Claire Parkinson, a senior scientist at Nasa’s Goddard Space Flight Centre, says increasing Antarctic ice does not contradict the general warming trend. Overall the Earth is losing sea ice at a rate of 35,000 sq km per year (13,514 sq miles).

“Not every location on the Earth is having the same responses to climate changes. The fact that ice in one part of the world is doing one thing and in another part ice is doing another is not surprising. The Earth is large and as the climate changes it is normal to see different things going on,” says Parkinson.

In a video made by Eco Audit reader and journalist Fraser Johnston, Dr Guy Williams, a sea ice scientist at the Tasmanian Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (Imas), says that even though it had fooled climate models the increasing sea ice was well understood by scientists.

“In some ways it’s a bit counterintuitive for people trying to understand how global warming is affecting our polar regions, but in fact it’s actually completely in line with how climate scientists expect Antarctica and the Southern Ocean to respond. Particularly in respect to increased winds and increased melt water,” said Williams.

To explain why Antarctic sea ice fails to fit comfortably with a simple ‘warmer world, less ice’ narrative, it is necessary to understand that the climate system has many layers of competing effects. Often only the largest of these will be obvious or detectable.

Currently, the effect of greenhouse gases is being overshadowed by other local climate phenomena, says Turner. “By far the biggest impact has been the ozone hole. The signal of increasing greenhouse gases is buried beneath all the other signals.”

The depletion of the ozone layer above Antarctica during last century by emissions of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) has caused an overall cooling trend on the continent.

Ozone itself is a greenhouse gas and its reduction has seen more heat reflecting back into space. Although the ozone hole has begun to show the first signs of recovery, levels are still significantly reduced. Parkinson says the loss of ozone is probably the second largest human impact on global climate after carbon dioxide.

One of the effects of ozone loss on the Antarctic has been the increasing frequency and ferocity of winds and storms around the continent. According to Turner, ozone depletion has caused winds in the Southern Ocean to increase by 15-20%. In particular, the cooling trend may have caused a low pressure system in the Amundsen sea to increase in intensity or frequency.

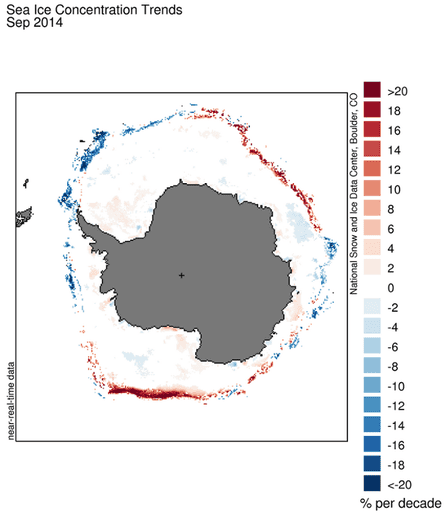

This vortex sucks air from the frozen inside of the continent and it rushes out over the Ross Sea to the west. This is where 80% of Antarctica’s ice expansion has occurred.

The effect of the intensifying winds is coupled with a massive dump of cold, fresh water into the Ross Sea from the Pine Island glacier. This water, which floats on the surface, is less dense, colder and freezes more easily than the sea water below, and when it is struck by storm winds from the continent it forms ice floes.

It is estimated that the Pine Island glacier alone loses so much water that it is responsible for 10% of global annual sea level rise (which is about 3mm per year). Warm currents come from deep water and heat the underside of the ice sheet, causing it to melt. Turner says this process probably has little to do with global warming. “Pine Island seems to be an ongoing retreat that could have been going on for 10,000 years,” he says.

Further complicating the picture is the El Niño Southern Oscillation (Enso), which Turner believes is a factor in both the increase of storms and the warm currents that melt the ice.

Sea ice in Antarctica is very different to its northern counterpart. In the south, ice melts away almost completely every year. The new ice produced each year is thinner and more volatile than the older more stable ice in the Arctic. These large fluctuations, said Turner, meant the “input” of greenhouse gases was not yet the dominant force in the region’s climate.

Parkinson says that it is likely that global warming will eventually overtake these other factors.

“A few decades from now it might turn out that Antarctic ice decreases. I don’t think that would be a surprise at all. If warming reaches the level people think it might in the next few decades then its going to eventually reach the Antarctic and the sea ice will start to decrease.”

Have your say

The Eco Audit relies on input from you. Follow Karl Mathiesen’s Facebook page for upcoming topics, suggest issues you want to see interrogated and read commentary from this piece.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion