Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler today stated what is obvious to US Internet users: for broadband speeds fast enough to serve modern homes, competition simply does not exist in most of the country.

The numbers are OK if you use the FCC’s outdated broadband definition of 4Mbps downstream and 1Mbps upstream. But the FCC is proposing to boost the download portion of the definition to 10Mbps and considering whether to raise the upstream portion. Even 10Mbps doesn’t cut it in homes where numerous devices connect to the Internet, however, Wheeler said.

“A 25Mbps connection is fast becoming ‘table stakes’ in 21st century communications,” Wheeler said in a speech this morning at 1776, a self-styled "hub for startups" in Washington, DC (transcript).

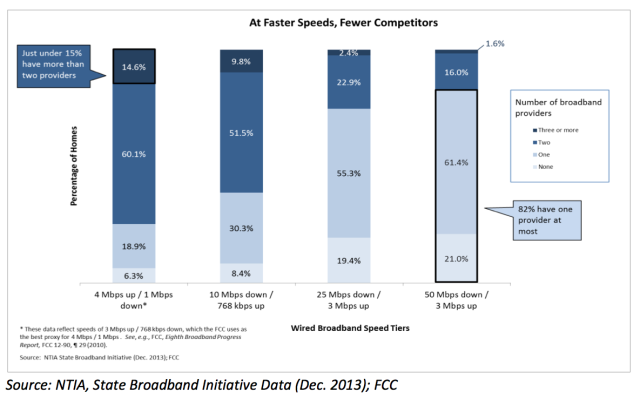

About 80 percent of Americans homes could buy 25Mbps broadband, but generally from only one provider, he said. “At 25Mbps, there is simply no competitive choice for most Americans,” Wheeler said. “Stop and let that sink in... three-quarters of American homes have no competitive choice for the essential infrastructure for 21st century economics and democracy. Included in that is almost 20 percent who have no service at all! Things only get worse as you move to 50Mbps where 82 percent of consumers lack a choice.”

At 4Mbps and 10Mbps download speeds, “the majority of Americans have a choice of only two providers,” Wheeler said. “That is what economists call a ‘duopoly,' a marketplace that is typically characterized by less than vibrant competition.” The situation is especially bad in rural areas, he said.

Even where consumers have options, it’s hard to switch providers, Wheeler said.

“But even two ‘competitors’ overstates the case,” he said. “Counting the number of choices the consumer has on the day before their Internet service is installed does not measure their competitive alternatives the day after. Once consumers choose a broadband provider, they face high switching costs that include early-termination fees, and equipment rental fees. And, if those disincentives to competition weren’t enough, the media is full of stories of consumers’ struggles to get ISPs to allow them to drop service."

That statement was a reference to the notorious phone calls with Comcast customer service representatives.

Wheeler did not directly address one Comcast-related question on the minds of those paying attention to the speech: whether he will oppose the company's proposed acquisition of Time Warner Cable (TWC). But he made it clear that he doesn't buy one of Comcast's arguments, that it should be allowed to buy TWC because it faces such robust competition from DSL and cellular networks.

Wheeler dismissed DSL as a viable competitor to cable, at least today, saying that “traditional DSL is just not keeping up, and new DSL technologies, while helpful, are limited to short distances.”

Wheeler said that wireless is an important part of building competition, but he doesn’t buy the argument that it’s already a substitute for home Internet service.

“We have great hopes for wireless as a potential substitute for fixed broadband connections. But today it seems clear that mobile broadband is just not a full substitute for fixed broadband, especially given mobile pricing levels and limited data allowances,” Wheeler said. “In the end, at this moment, only fiber gives the local cable company a competitive run for its money. Once fiber is in place, its beauty is that throughput increases are largely a matter of upgrading the electronics at both ends, something that costs much less than laying new connections. While LTE and LTE-A offer new potential, consumers have yet to see how these technologies will be used to offer fixed wireless service.”

Google Fiber has proven that competition works in the few parts of the country that Google has built or is considered building networks, Wheeler said.

“We’ve seen what happens when companies like Google bring new competition in the form of gigabit service to cities like Kansas City and Austin,” he said. “In Kansas City, the cable company responded with its own upgrade to gigabit service; in Austin, it was the telephone company that upgraded competitively with its own ultra-high-speed service. In fact, AT&T has announced plans to deploy gigabit fiber to 21 major metropolitan markets. Many of these are in same markets where Google has announced plans to lay fiber.”

Nothing drastic in Wheeler's four-part plan

So what will the FCC do? Wheeler laid out four priorities, though none of them seem likely to bring a major overhaul to US broadband.

“First, where competition exists, the Commission will protect it,” he said. “Our effort opposing shrinking the number of nationwide wireless providers from four to three is an example. As applied to fixed networks, the Commission’s Order on tech transition experiments similarly starts with the belief that changes in network technology should not be a license to limit competition.”

The FCC has helped prevent T-Mobile from being acquired by competitors AT&T and Sprint, as Wheeler noted. The “tech transition” order greenlighted AT&T trials that will help plan for the eventual replacement of the Public Switched Telephone Network with an all-Internet Protocol network.

Second on Wheeler’s list, “where greater competition can exist, we will encourage it. Again, a good example comes from wireless broadband. The ‘reserve’ spectrum in the Broadcast Incentive Auction will provide opportunities for wireless providers to gain access to important low-band spectrum that could enhance their ability to compete. Similarly, the entire Open Internet proceeding is about ensuring that the Internet remains free from barriers erected by last-mile providers.”

The FCC’s Open Internet proposal has been criticized by consumer advocates for allowing ISPs to create “fast lanes” in which Web services could pay for prioritized access to consumers. Still, Wheeler believes that his proposal of minimum service requirements will prevent harm to consumers.

“Communications policy has always agreed on one important concept: the exercise of uncontrolled last-mile power is not in the public interest,” he said. “This has not changed as a result of new technology. When network operators have unrestrained last-mile power, public policy can step in to protect consumers and innovators. When cable companies, for instance, were accused of using their control over the last-mile distribution of video programing to harm competition by keeping content from others, Congress stopped that practice in the 1992 Cable Act. There are two important lessons from this: First, last-mile power cannot be a lever for gaining an unfair advantage. Second, rules of the road can provide guidance to all players and, by restraining future actions that would harm the public interest, incent more investment and more innovation.”

The third of Wheeler’s four priorities is that “where meaningful competition is not available, the Commission will work to create it. For instance, our efforts to expand the amount of unlicensed spectrum create alternative competitive pathways. And we understand the petitions from two communities asking us to pre-empt state laws against citizen-driven broadband expansion to be in the same category, which is why we are looking at that question so closely.”

Here, Wheeler noted Google’s effort to get detailed maps of city infrastructure and easy access to permits. This “highlights the importance of timely and accurate information about and access to infrastructure, such as poles and conduit. Working together, we can implement policies at the federal, state, and local level that serve consumers by facilitating construction and encouraging competition in the broadband marketplace,” he said.

The fourth and final item on Wheeler’s list was that “where competition cannot be expected to exist, we must shoulder the responsibility of promoting the deployment of broadband. One thing we already know is the fact that something works in New York City doesn’t mean it works in rural South Dakota. We cannot allow rural America to be behind the broadband curve. Our universal service efforts are focused on bringing better broadband to rural America by whomever steps up to the challenge—not the highest speeds all at once, but steadily to prevent the creation of a new digital divide.”

What of Comcast/TWC?

All of that sounds pretty good, but Wheeler, a former lobbyist for the cable and wireless industries, didn’t propose more dramatic options that would anger incumbent Internet service providers. He did not call for treating broadband as a utility, nor for requiring network operators to lease access to last-mile infrastructure, a method that has promoted competition outside the US.

The transcript of Wheeler's speech also says nothing about the Comcast/TWC and AT&T/DirecTV mergers pending before the commission.

Consumer advocates praised Wheeler for acknowledging that the US broadband market isn’t competitive enough, but they called on him to take stronger action. “The real proof will be in the agency's actions and not just its speeches,” Free Press Policy Director Matt Wood said in a statement. “Beyond blocking the disastrous merger proposals in front of it, the FCC needs to take concrete steps to promote competition. It must understand that bedrock principles like nondiscrimination apply even in competitive and deregulated telecom markets. And it should start by actually collecting and better analyzing data on broadband competition and pricing—information the big ISPs have been so reluctant to turn over to the agency and to independent researchers studying this issue."

reader comments

87