Buy

Resources

Entertainment

Magazine

Community

In This Article

Category:

Car Culture

Camille Jenatzy, with his wife, driving La Jamais Contente in a victory parade.

Land-speed record racing was not exclusively a 20th century phenomenon. At the close of the 19th century, the quest for the fastest documented motorized speed was viewed by horseless carriage manufacturers as a way to demonstrate the superiority of their wares. Though his name is all but lost to history today, Camille Jenatzy was the first human being to crack the 100 kilometer-per-hour (62 MPH) barrier, as well as the first to drive a car built specifically to set a new land-speed record.

Born to an affluent family in Schaerbeek, Belgium, in 1865, Jenatzy studied civil engineering in school, but found that his real passion lay elsewhere. Fascinated by the newly emerging automotive industry of the late 1890s, Jenatzy followed his father's footsteps into manufacturing, but instead of producing rubber goods, the younger Jenatzy focused on building battery-powered automobiles. Only the wealthiest individuals of the day could afford such mechanized conveyances, and Jenatzy was hardly the first to market with an electric car in Europe. Motor racing, a sport that was exploding in popularity, seemed a logical way to demonstrate the capabilities of an automobile, so Jenatzy entered his first race, a hill climb, in November of 1898. Driving an electric car of his own manufacture, Jenatzy set the fastest time of the day, averaging 17 MPH over the muddy 1.8 kilometer course. Racing glory, Jenatzy believed, would soon translate into sales success.

A Jenatzy-built phaeton, circa 1900.

His fame would be fleeting. Just three weeks later, Count Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat would set an official land-speed record of 39.2 MPH behind the wheel of an electric automobile built by rival manufacturer Jeantaud. Jenatzy had been invited to participate in the contest of speed, but a prior engagement prevented his attendance; determined to claim a speed record of his own, Jenatzy challenged Chasseloup-Laubat to a rematch, to take place in early 1899 on a deserted and level stretch of road just west of Paris.

On the 17th of January, both men arrived in Acheres, determined to go home victorious. Jenatzy drove first, establishing a new land-speed record of 41.4 MPH and easily besting the previous record. Chasseloup-Laubat was not to be outdone on that day, and his run was clocked at 43.7 MPH, despite the fact that his motor was destroyed 200 yards from the finish. Defeated but not dismayed, Jenatzy demanded another rematch, to take place in just 10 days' time. This time, luck would be on his side; Jenatzy posted a new record speed of 49.9 MPH, but Chasseloup-Laubat suffered another burned motor and was unable to complete his run.

Jenatzy celebrating his win in the 1903 Gordon Bennett Cup race. Remaining photos courtesy of Daimler AG.

Chasseloup-Laubat made his responding run on March 4, 1899, driving his Jeataud touring car (rebodied for the record attempt) to a maximum speed of 57.6 MPH. Nearly two months would pass before Jenatzy would challenge for a new record, but the time was spent wisely; instead of running a modified production car in the attempt, Jenatzy constructed the very first vehicle built specifically for land speed record racing. Dubbed La Jamais Contente, or "The Never Satisfied," the strange craft resembled a bullet perched atop an exposed automobile chassis. Though the lightweight partinium (an alloy made of aluminum, tungsten and magnesium) body was streamlined, the driver sat upright, with his torso in the slipstream; coupled with the exposed chassis components, any advantages gained by the aerodynamic shape of the body were all but negated by these design choices.

Using a pair of 25-kilowatt electric motors fed by batteries delivering 200 volts and 124 amps, La Jamais Contente produced approximately 68 horsepower. That was enough to propel Jenatzy to a top speed of 65.8 miles per hour, or 105.9 kilometers per hour, and on April 29, 1899, Jenatzy entered the record books as the fastest man automobile driver in the world, as well as the first to break the 100 KPH barrier in an automobile. Seduced by speed, Jenatzy would turn his attention to racing automobiles as well designing and building them, and in 1899 began his professional driving career behind the wheel of a Mors gasoline-electric automobile. Convinced he could build a better racer, Jenatzy entered the 1900 Gordon Bennett Cup race driving a Bolide, a gasoline-electric automobile of his own design. Not particularly competitive, Jenatzy gave up on the race when he lost his way en route, which may have contributed to his decision to walk away from racing in 1901.

The 1904 Mercedes 90hp racer. Jenatzy is shown second from left.

Neither his electric nor his gasoline-electric cars proved to be a success, and other Jenatzy designs (such as a patented magnetic clutch) only received limited exposure. By 1902, he was back in the driver's seat, but his season started off with a crash at the Circuit des Ardennes. A year later, he was driving for the Mercedes team, piloting a 90-horsepower racer in the Paris-Madrid; after overtaking 20 competitors, Jenatzy found himself in third position, a legitimate challenger for the win. As the car topped one of the course's final hills, however, his engine stumbled and he struggled to keep the car running. Driving with a bad misfire, Jenatzy limped the Mercedes across the day's finish line in 11th position. The cause of his engine trouble turned out to be nothing more than a fly sucked into the carburetor.

Know as "Le Diable Rouge" (the Red Devil) for his red beard and his exuberant driving style, Jenatzy would realize another significant victory in 1903. Prior to the start of the Gordon Bennett Cup race in Athy, Ireland, a fire at the Mercedes factory had destroyed the team's 90-hp racers. Scrambling to find cars to drive, Mercedes reached out to private owners in an effort to "borrow" 60-hp touring cars. Despite the horsepower deficit, Jenatzy drove his loaner Mercedes (owned by American Clarence Gray Dinsmore), stripped of most bodywork to save weight, to a commanding 12-minute margin of victory, returning the Gordon Bennett Cup to Germany with his win.

Jenatzy driving a 120-hp Mercedes racer at the 1906 French Grand Prix.

Jenatzy would continue in his role as a gentleman driver through 1908, when he drove his last international race at the Circuit des Ardennes behind the wheel of a Mors, finishing in 16th place. Though he raced a number of cars in his final years as a driver (including the Mors and a Pipe), his main automotive passion continued to be Mercedes, and he revealed a premonition to close friends that he would one day die in a Mercedes automobile. While he kept a 180-hp Mercedes racer for the odd sprint race or hill climb, by 1910 his attention had turned primarily to running the family's tire manufacturing business in Brussels. The odds of dying in a Mercedes grew more distant with each passing year.

Except that fate sometimes has a wicked sense of humor. While on a hunting trip with friends in the Ardennes in 1913, Jenatzy believed it would be humorous to hide behind a stand of bushes and mimic the grunts of a wild boar. So convincing was his act that a friend, Alfred Madoux, responded with a shotgun blast in the direction of the sounds (ignoring a primary rule of firearm safety: Know your target and what lies beyond). Despite the best effort of those in his party, Jenatzy succumbed to his injuries en route to the nearest hospital, while being transported, of course, in a Mercedes.

Recent

Photo: American Muscle Car Restorations

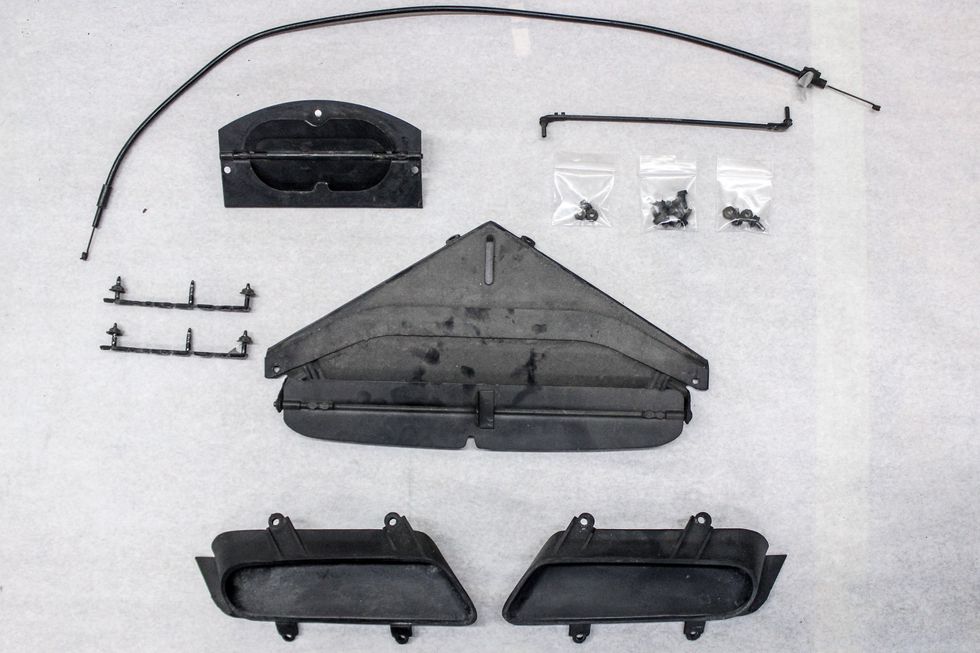

During the muscle car era of the 1960s and early 1970s manufacturers came up with some clever ideas to enhance their vehicles. Horsepower was king, but the stylistic solutions employed to separate the base models from their bigger cubic-inch performance-oriented models on the salesroom floor came to life in design departments. Those designs were then pushed by advertising agencies. Much of that differentiation employed the use of bright colors, stripes, wheels, and scoops. Arguably one of the most creative companies was Chrysler, with their Plymouth and Dodge line of performance cars. While some of the solutions employed were purely visual, others had a practical performance application baked into their design. We’re going to focus on one of Chrysler’s most iconic fresh air scoops, the Shaker, which was available on Plymouth ‘Cuda and Dodge Challenger R/T models in 1970 and 1971. If your E-body had option code N96 stamped on the data plate, or noted on the vehicle’s broadcast sheet, then it was equipped with what was initially called in some early sales brochures as the “Incredible Quivering Exposed Cold Air Grabber” before being changed later on to just “Shaker.”

For the individual that has one of these Shaker packages installed on their vehicle and is looking to do a full restoration on the various components utilized, there are different paths that can be taken. Some may opt for a simple sand and respray, while those looking to do a concours level restoration where the initial factory build process is replicated requires much more effort to pull off. As we focus on the complete makeover of the most visible component, the Shaker bubble, we turn to one of the premier shops that has mastered this technique, Mike Mancini’s American Muscle Car Restorations (AMCR), to show us how they tackle this complex process. Over the years they’ve done numerous OE Gold Certified restorations on Shaker-equipped cars, which has given them a wealth of information. Their approach has been to collect and document the information that has been gathered from a broad range of original vehicles to duplicate that initial build process. We will look at the steps in their process, but before we dive in, we’re going to give you some information on how these parts were manufactured for Chrysler because there is a direct correlation on how they are correctly restored.

Photo: Chrysler Corporation/Stellantis

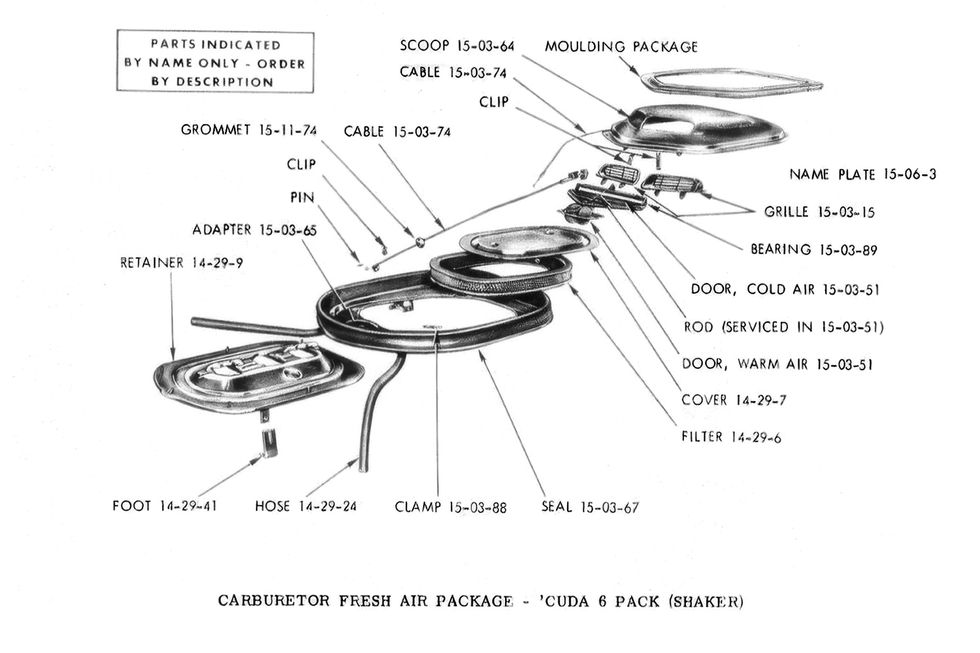

The first misconception that some individuals have on items like this is that they were fabricated or assembled in house by Chrysler. The reality is that the Shaker fresh air package was farmed out to Fram in Chatham, Ontario for final assembly. As shown in the parts manual, the illustration shows the complexity of the entire assembly which Fram was responsible for delivering to the Hamtramck and Los Angeles assembly plants. The parts that made up this package were sourced from several vendors. Fram in Stratford, Ontario, a subsidiary of the parent company, was responsible for the fabrication of the various base plates, which were designed to be mounted on a variety of different engine and carburetion options, and an outer adapter ring. They also manufactured the various air cleaner lids, filters, and the air doors fitted to the bubble, however, the rest of the parts were sourced from several US and Canadian suppliers. These assemblies, when shipped to both plants, were turnkey - right down to the emblems, ready to be installed. They were shipped on bedsteads that held sixty units each.

Photo: Chrysler Corporation/Stellantis

Chrysler’s early promotional material for the 1970 Barracuda line, which included a Hemi-equipped 'Cuda on the cover of the sales brochure showed the Rallye Red bubble prominently featured. In 1971, the sales brochure had a 340-equipped 'Cuda on the cover with a black Shaker bubble. During the two-year production of Shakers only the black, silver, and red finishes were approved by Chrysler and showed up in internal Fram literature. Part of the overall assembly process required them to paint the bubbles and the first batch sprayed in 1970 were done in Argent Silver. This was a task that Fram was not equipped to perform due to the requirements needed to spray the textured paint, and the adhesion problems encountered because of the bubble’s material composition. Chrysler executives also asked for a few bubbles to be painted Rallye Red for use in their print materials and television ads, and there were very few installed and sold on cars early in the production run. It is rumored that Chrysler opted to discontinue the Rallye Red option because of sun glare issues due to the bubble’s curvature.

Photo: Chrysler Corporation/Stellantis

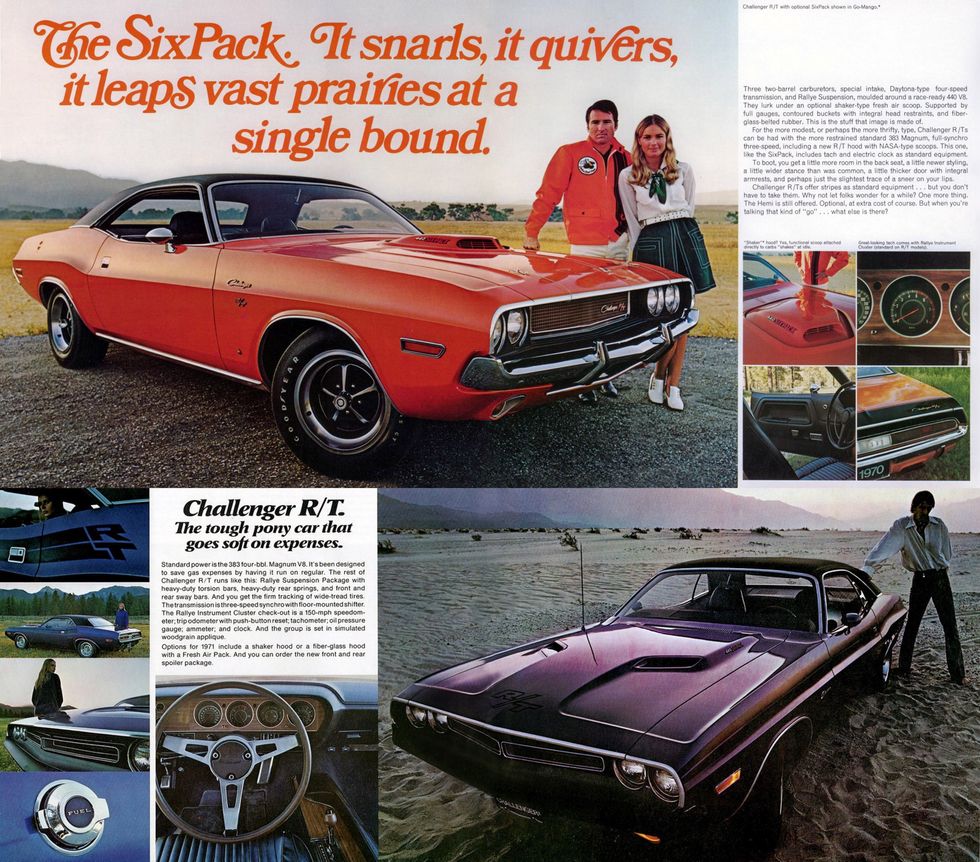

<p>The Shaker assemblies for the Dodge Challenger were identical to the ones fitted on the ‘Cuda (except for the emblems) and covered the same engine and carburetion options for both years. The sales brochure for the 1970 Challenger showed a Go-Mango 440 Six Pack-equipped car with a bubble that was color-matched to the body. There was also a TV commercial with a Plum Crazy 1970 Challenger 440 Six Pack convertible with a color-matched bubble. Fram was asked to paint a few bubbles in Go-Mango for their print materials, but no information is available on the Plum Crazy bubble. Neither of these colors show up in internal Fram documentation as being available for production. Unlike the 'Cuda, the Challenger Shaker option was fraught with issues due to what is believed to be a design flaw in the hood, which forced Chrysler to suspend its production. A completed batch of Argent Silver Shaker assemblies that were sent to the assembly plants were shipped back to Fram due to the halt on hood availability. Once the design issues were resolved and the Shaker option was once again on the table late in the 1970 model year, the Argent Silver Challenger bubbles that Fram was sitting on were shipped back to the assembly plants and used until they ran out, at which point the Organosol Black was phased in during the 1971 production run.</p>

Mopar Shaker Scoop Restoration - Process

Photo: John Machaqueiro

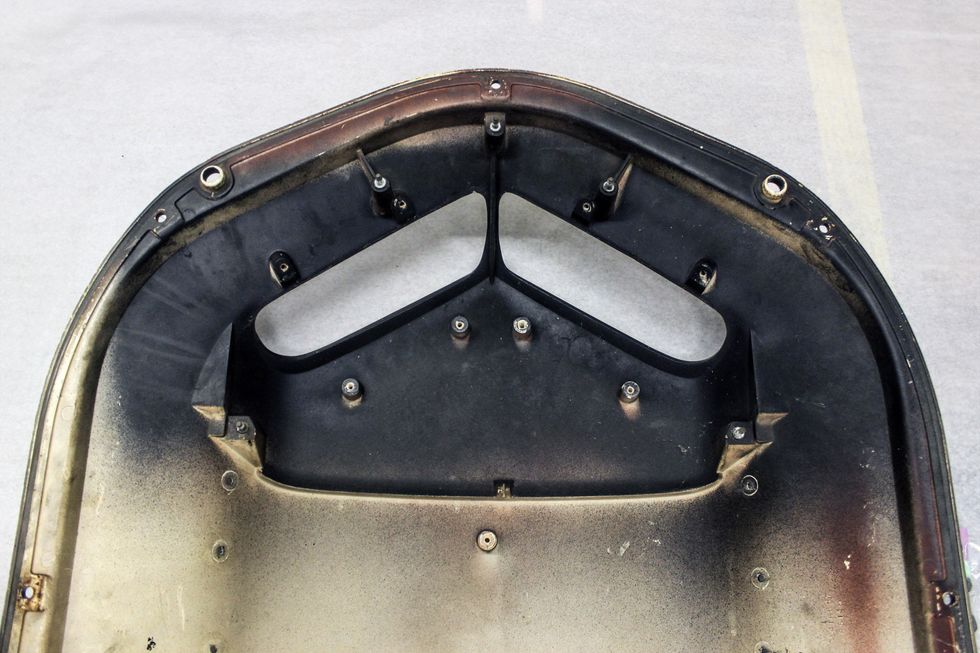

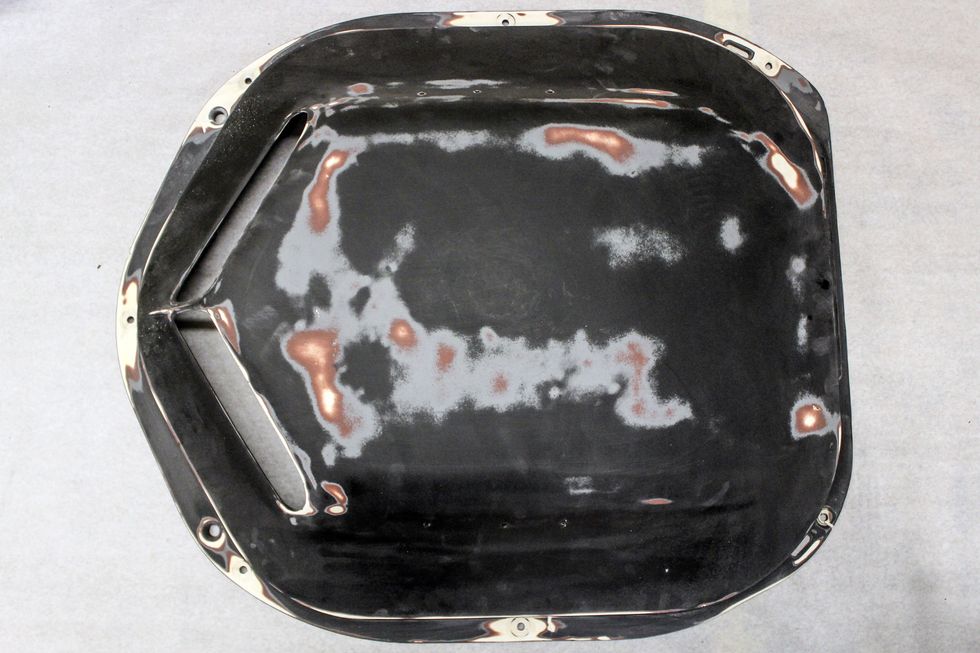

<p>The bubble that we will be using to illustrate the AMCR process is from a <a href="https://www.hemmings.com/classifieds/cars-for-sale/plymouth/cuda/1971" target="_blank">1971 Plymouth 'Cuda</a> equipped with a 340. This bubble was for the most part complete and in excellent condition. It’s from an original Shaker car that was built on October 12, 1970, and was painted in PPG Organosol Black lacquer, which was the only color available for a bubble on 'Cudas built for the 1971 model year. When AMCR restores a Shaker bubble, they will have the correct black or silver finish applied in the original PPG lacquer.</p>

Photo: John Machaqueiro

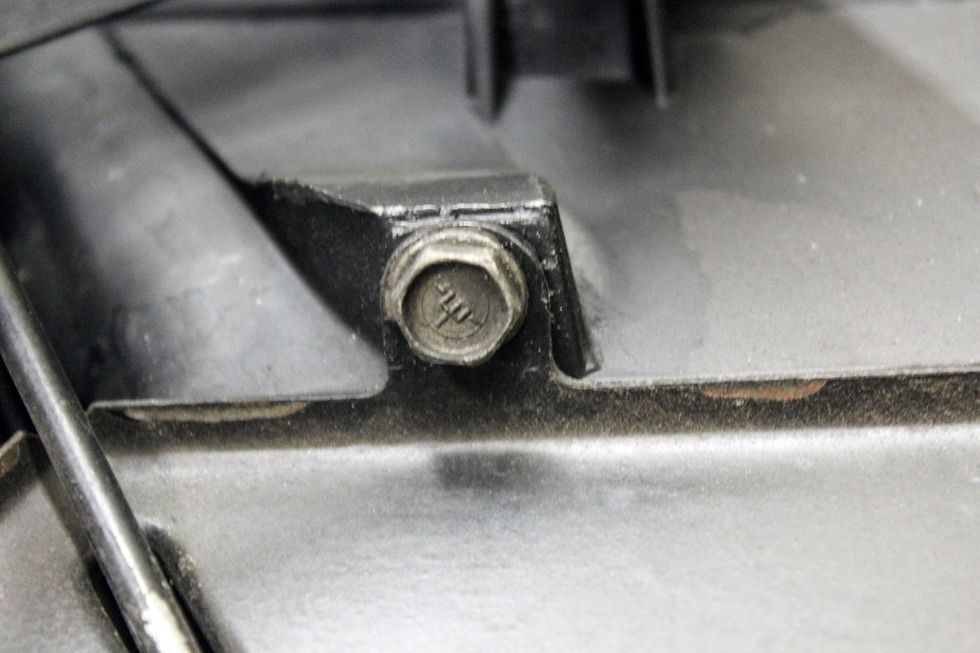

The finished assembly brings this Shaker bubble back to its original look as it rolled out of the Hamtramck assembly plant. Worth pointing out on these assemblies are the emblems. While they look identical to what would have come on the standard Rallye hood, they are in fact different. Shaker bubble emblems used a longer three pin emblem that is retained using speed nuts, while the emblems used on the Rallye hood were a shorter two-pin design that used plastic expansion sleeves to hold them in place.

Keep reading...Show Less

Using generational reference points, if you fall between the later "Gen X" and the early "Millennial" generations, a 1980s Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme is likely to be involved in your history at some point. For many, this was the hand-me-down car from Mom and Dad or the from the grandparents as they moved on to Chevrolet Tahoes, Ford Explorers, Northstar-powered Cadillacs or whatever else that was catching their attention. For others, this was an easy-to-find used car bargain that was most likely to be reliable and comfortable, with a bit of a kick under the hood and a bit of class for the outside world. For a long time, a Cutlass Supreme was a common sight on the roads, even as front-wheel-drive V-6 powered sedans became the normal for families, because a great new car made for a great used car.

Mechanically, what wasn’t to like? The Cutlass nameplate had been one GM’s best-selling for years at that point, and the G-body platform was a robust rear-drive body-on-frame design that offered everything from safe-and-sane V6 offerings to the Oldsmobile 307 V-8. Automatic transmissions meant an easier learning curve for young drivers, and young and older both could agree that the two-door body was both sporty-looking with just the right touches of Oldsmobile formality. Similarly, there weren’t any complaints about a Cutlass’s interior appointments. It was an easy sell for both ends of the argument.

This 1986 Cutlass Supreme Brougham currently available on Hemmings' Marketplace is a great visualization of what you could expect to see in high school parking lots through the mid-to-late 1990s. There’s minor wear, like some cracking paint and the faded “Cutlass” branding on the mud flaps, but it still presents beautifully. There’s a set of custom wheels attached (a tasteful set of Cragar S/S wheels, in this case) and that’s about it, because car parts are expensive for a high school junior’s budget. The suspension will still be Oldsmobile-level soft and cushy; the exhaust will just be a low, mellow tone that came with the car from factory (because Dad warned you about cutting off the muffler to make it louder) and the sound system was still stock (again, because stereo equipment wasn't cheap). The parents were happy because it started every time, the fuel economy was tolerable and there was a good chance that you would walk away from a crash in something with a frame underneath it. You were happy because it had a V-8, only had two doors, wasn't the size of Aunt Judy's Delta 88, and could spin a tire if you hit the throttle hard enough.

With twenty years having passed since the end of grunge rock and the dawn of the Internet age, how many readers immediately think back to the Cutlass of their past? Your author has had owned four of them, plus the cars of friends, of co-workers, or the cars that he looked at as possible projects throughout the years. With values still very approachable and plenty of support in the aftermarket, there is no reason you can’t turn the clock back every time you twist the key.

Keep reading...Show Less

Interested in a new or late model used car?