As tomorrow's FCC net neutrality vote looms, Ars has been sharing as much of our reporting on the topic as possible. And this week, a longtime reader nudged us about this classic on the FCC's Carterfone decision from nearly 50 years ago. "This story is extremely relevant to the current Net Neutrality debate in that it provides a historical precedent to debunk arguments about regulation stifling innovation," the reader writes. "It shows that this battle is not a recent development, but goes back decades. Might you consider republishing it so that this story can get new exposure?"

Ask nicely (and offer a great suggestion), and you shall receive. This story originally ran in June 2008. Below, it appears unchanged except for updates to the time frame (the piece originally ran on the decision's 40th anniversary).

Nearly 50 years ago, the Federal Communications Commission issued one of the most important Orders in its history, a ruling that went unnoticed by most news sources at the time. It involved an application manufactured and distributed by one Mr. Thomas Carter of Texas. The "Carterfone" allowed users to attach a two-way radio transmitter/receiver to their telephone, extending its reach across sprawling Texas oil fields where managers and supervisors needed to stay in touch. Between 1955 and 1966, Carter's company sold about 3,500 of these apps around the United States and well beyond.

In the end, however, Carterfone's significance extends far beyond the convenience that Thomas Carter's machine provided its users over a decade. It is no exaggeration to say that the world that Ars Technica writes about was created, in good part, by the legal battle between Carter, AT&T, and the FCC's resolution of that fight—its Carterfone decision. The Carterfone saga starts as the appealing tale of one developer's willingness to stick to his guns. But it is really about the victory of two indispensable values: creativity and sharing.

Neither just nor reasonable

The dominant telephone company in the United States fiercely opposed Carterfone. AT&T and the last surviving independent telco, the southwest's General Telephone, told their customers that they should not use the attachment because it was a "prohibited interconnecting device." To be fair, that was true, legally speaking. Americans bought the vast majority of telephone equipment from AT&T's Western Electric company because they had to, specifically because of FCC Tariff Number 132: "No equipment, apparatus, circuit or device not furnished by the telephone company shall be attached to or connected with the facilities furnished by the telephone company, whether physically, by induction or otherwise."

Thomas Carter thought that this was bunk. He took AT&T and General Telephone to federal court, arguing that their warnings to consumers represented a violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. In 1966 the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit agreed that they would decide the suit —but not before the FCC reconsidered Tariff Number 132. The agency then appointed an investigator to look into the matter.

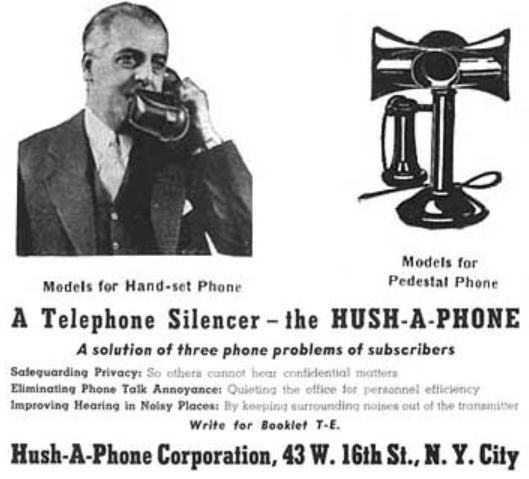

AT&T may have thought it had an ally in the FCC circa 1966, but that was no longer the case. The Commission had been chastened by an earlier controversy over a device called the Hush-A-Phone. This ridiculous proceeding involved AT&T's objection to a small plastic receiver snap-on which allowed business phone talkers to chat more quietly. The FCC took an astounding seven years to thoughtlessly back Ma Bell on the issue, only to see its decision slapped silly by an appellate court. "To say that a telephone subscriber may produce the result in question by cupping his hand and speaking into it, but may not do so by using a device which leaves his hand free to write or do whatever else he wishes, is neither just nor reasonable," the bemused judges observed in 1956.

Now the best that AT&T's clever lawyers could do was convince the FCC to let them write a new policy with a codicil allowing for non-electric applications like Hush-A-Phone. But the phone giant still insisted that Carterfone posed a danger.

It was June 26, 1968 when the FCC acted on Carterfone. Robert F. Kennedy had been buried two weeks earlier. In Czechoslovakia, followers of the "Prague Spring" fought against Communist rule. Students revolted against mindless bureaucracies at Columbia University, in Paris, in Seoul, in Mexico City. In these stormy times almost no one noticed as the FCC's Commissioners quietly rebelled against the world's biggest telco, unleashing the future.

reader comments

70