A couple of summers ago, John Cusack was at a baseball game, watching the Chicago White Sox play.

“In the next box over there was a gorgeous girl – young, but she was looking right at me,” he says. I went to go to the bathroom and I saw her get up. I thought: ‘Ohhhh … she’s going to come and meet me and I’m gonna … you know …’ I was going to be really flattered. And she was, like: ‘I have to take a picture of you! You’re my mom’s favourite actor.”

And so it goes. The twentysomethings crushing on Cusack in 1989 have become mothers. Their daughters weren’t raised on Say Anything’s boombox scene. They knew him from the iffy rom-coms, corny psychological thrillers – or simply because Mom was a big fan.

The baseball scene is one that could have been plucked from Maps to the Stars, featuring Cusack as a millionaire self-help guru. David Cronenberg’s first film shot in the US, Maps is a fever dream of modern celebrity. A savage Hollywood takedown that riles the studio system for its absurdity, then vilifies those obsessed with fame. It’s also an ensemble drama parading some of the biggest names in Hollywood: Cusack, Robert Pattinson, Julianne Moore, Mia Wasikowska. They promote the film as every other: by walking the carpet, smiling into flashbulbs and holing up in hotel suites to tell journalists about the real, fake Hollywood behind the fake, fake one. Sometimes the parallels become so close the lines start to blur.

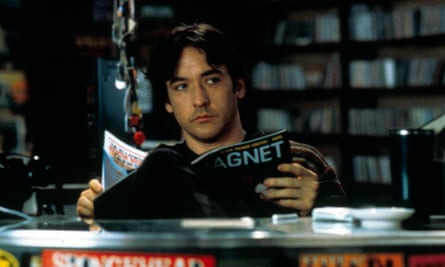

At 48, Cusack looks pretty much as he did onscreen in the 80s, or 90s, or any time since. He’s hangdog but amiable, folded into the sofa with one leg propped on the coffee table. He wears a long black overcoat and black jeans with a rip in the knee. There’s an air of benign tolerance, just like in the movies. He sporadically breaks into a smile, which seems to surprise him as much as me. The only anomaly – the detail the screenwriter would snip for being too out of character – is the e-cigarette. I had read Cusack liked a cigar, which would seem more fitting. Instead this blue pipe waves around the eyeline, letting out tiny guffs of odour-free smoke.

In Maps, Cusack plays Stafford Weiss, a therapist who got rich off a cocktail therapy (one part Freudian psychoanalysis, one part deep-tissue massage, a generous measure of bullshit) that’s guzzled by the showbiz elite. They want a quick fix for their deep insecurities. Stafford lays his hands on his followers and kneads out emotional pain. “You saw heavy combat as a child,” he tells Havana Segrand (Moore), a faded fortysomething star who weeps her mommy issues into a yoga mat. “If we can name it, we can shame it.”

“LA seems to be a place where a guy can say he’s a ‘life-coach-channeller-masseur’,” says Cusack. “It just seems to be ripe with all these frontier crazies. People are looking to turn their pain into beautiful art, but they also want to be famous. And there’s so much money – so of course all the predators come in.”

Age is currency in the Hollywood of Maps. Stafford’s 13-year-old actor son, Benji, holds a studio to ransom over the pay deal for the next instalment of his “Bad Babysitter” franchise. A 26-year-old actress is “menopausal” according to her teenage co-stars. Havana Segrand is losing her mind because her credit’s running out. The film’s writer, Bruce Wagner, has dismissed the idea that Maps is satire. He has, he claims, heard every line of the script said in earnest.

Which bits of the film reflect Cusack’s own experience? “Almost everything,” he says.

“I got another 15, 20 years before they say I’m old. For women it’s brutal. Bruce’s thing about if you’re 26, you’re menopausal? It’s only absurd because it’s a little bit further than the truth.”

“I have actress friends who are being put out to pasture at 29. They just want to open up another can of hot 22. It’s becoming almost like kiddie porn. It’s fucking weird.”

Cusack, born and raised in Evanston, Illinois, made his film debut at 16, was recognisable by 18 and a star by 22. He cut his teeth at the Piven Theatre Workshop, founded by theatre directors Joyce and Byrne Piven, the parents of Entourage star Jeremy (a childhood friend and regular co-star). He found a role in film as a teen idol when John Hughes and Rob Reiner required his puppyish charm for a bit-part in Sixteen Candles and the lead in The Sure Thing respectively. It was luck, he’s said: “I was 16 when they wanted to make films about 16-year-olds in Chicago.”

He became iconic thanks to Say Anything, Cameron Crowe’s first film. Cusack played Lloyd Dobler, the high-school slacker determined to romance Diane Court, the cosseted class valedictorian. Lloyd – long overcoat, benign demeanour, lovely smile – shepherded Diane through her first house party, was sweet to the clients at her dad’s retirement home. Diane fell for Lloyd. The public fell for Lloyd. And Cusack.

“People would look after you when I was a kid,” he says. “There were good people in the business. When I came to LA Rob Reiner said: ‘Come stay at my house.’ He taught me. I worked with Pacino [in 1996 crime drama City Hall]. Pacino would talk to you and mentor you. Now it’s different. The culture just eats young actors up and spits them out. It’s a hard thing to survive without finding safe harbour.”

Maps to the Stars broods on how celebrity corrupts the fallible. It’s also something of a bitchfest; a blood-letting that Cusack enjoys having a stake in. Hollywood today is closer to Wagner’s vision than we realise, he says. It’s no longer a place, it’s a nostalgic idea. The mega-corporations have stepped in, bringing with them the era of the 50-producer movie. In modern Hollywood the franchise is king, the star is used as leverage. “You can’t make it up,” says Cusack. “It’s a whorehouse and people go mad.”

Young stars should seek shelter wherever they can, he says. His Maps co-star Robert Pattinson is going about it the right way. The film is Pattinson’s second collaboration with Cronenberg after the Don DeLillo adaptation Cosmopolis, which helped R-Patz break from Twilight.

“I think it’s very wise – and speaks highly of Robert [Pattinson] that he’s formed a thing with David. He can try to be good and have a space where he’s not just this product that’s going to be followed around by TMZ. That speaks to the healthier instincts of the guy. I don’t know if there’s that space for other people.”

There’s no place for the jaded in Maps to the Stars. Everyone’s too hungry for fame to question it, too desperate to take stock. Cusack isn’t bothered by his own celebrity (“It’s a blessed life”), but he’s vocal about privacy. He’s a founding member of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, a not-for-profit group that uses crowdfunding to help news organisations retain their confidentiality and independence. His fellow board members include legendary Vietnam whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, former Guardian journalist Glenn Greenwald and Edward Snowden.

“We could argue now that we don’t have a functioning democracy,” he says. “I would. That’s why I picked that thing to fight. I know that this [he grimaces at my iPhone] can be turned into a microphone and they can be taping our conversations right now. It’s not that I’m paranoid. I know it.”

He writes for the Huffington Post on politics and takes up the cause on Twitter when he can. But the modern mentality is to pigeonhole, he says.

“There’s a slicing and dicing of what people should think about,” he says. “Why can’t you make larger connections? I made a couple of films – Max [Cusack plays a fictional Munich art dealer conflicted over exhibiting work by the young Adolf Hitler] and War Inc [a satire about US economic expansionism] that were radical, political films. War Inc was interesting because it was a reaction to the opening up of new markets at the point of a gun in Iraq.

“We’re seeing that happen now. War Inc was savaged by regular movie critics. But then there was a whole realm of people who don’t write about entertainment who were writing about it totally differently.”

Not that he blames film critics entirely: “Why wouldn’t you have contempt for the movie business?” he says. “It sucks most of the time.”

The quality of Cusack’s films has always been scattershot. He follows a pattern – the occasional great film, a few fair, a couple of terrible. Among the great is Stephen Frears’s The Grifters, the 1990 neo-noir that saw him break up with the teen genre by playing a con artist fighting Oedipal urges. His stocked bubbled up again thanks to Woody Allen’s Bullets over Broadway, in which he plays an idealistic playwright forced to cast a talentless gangster’s moll to get his play produced. A lucky run between 1999-2000 (Pushing Tin, Being John Malkovich, High Fidelity) was squelched by Serendipity, a soggy rom-com with Kate Beckinsale.

He works a lot (he’s up to 76 credited roles), fielding triumphs (Grosse Point Blank, co-written by Cusack, about a disillusioned hitman attending his school’s 10-year reunion) and slumps (Must Love Dogs). He recognises the turkeys, thinks the audience are savvy enough to clock them too. He makes the best of the bad so he can make something else. At least, that’s how it used to work.

“My friend Joe Roth ran Disney [until 2000],” he says. “He made things like The Rock and Con Air to make shareholders happy, but then he also gave six or seven slots to people he liked. I got to make High Fidelity and Grosse Point Blank. Spike Lee got to make Summer of Sam. Wes Anderson got to make Rushmore. I had that memory of film and that’s gone.”

The whole “one for you, one for them” system has broken down, he says: “Now it’s six for them – with a committee cutting the film who weren’t part of making it – and maybe one for you. If I could do something like sell watches in China, then I would do that and just make movies like Maps.”

He doesn’t sound depressed, just defeated. His eyes keep drifting to a poster for Maps to the Stars that has been propped up behind me – the film being sold to the leverage. The poster shows a walk of fame star on fire. The flames lick at the cast and crew list above. After Cronenberg and Pattinson, Cusack’s name would be next to burn. I’m not sure he’d mind that much.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion