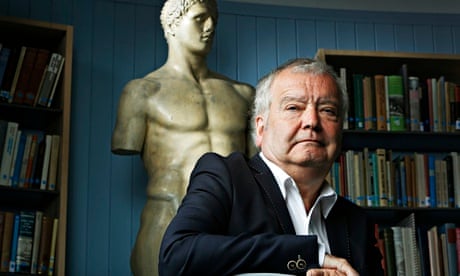

Scotland's leading historian has delivered a major boost to the campaign for Scottish independence with the announcement that he will be voting yes in the forthcoming referendum.

The eagerly awaited announcement by Sir Tom Devine, made in an interview with the Observer, will provide much-needed support to the pro-independence campaign, which has seen support for a yes vote stall in recent weeks.

Neither side in the campaign has openly courted Devine, but each has been eager to receive the endorsement of a man who is considered to be Scotland's foremost academic and intellectual.

The professor of Scottish history counts several senior figures on both sides among his friends, including Gordon Brown, the former Labour prime minister and now a driving force of the no campaign. Last week he also shared a platform at the Edinburgh book festival with the Scottish first minister, Alex Salmond. The latest news will be welcomed by Salmond, who was perceived to have performed below par in the recent televised head-to-head debate with Alistair Darling, leader of the no campaign.

In an exclusive interview, Devine said that at the outset of the campaign he had been a firm no supporter, though he had favoured a "devo-max" arrangement with extra powers devolved to Holyrood. He had been persuaded by what he believes has been a flowering of the Scottish economy in a more confident political and cultural landscape. "This has been quite a long journey for me and I've only come to a yes conclusion over the last fortnight," he said.

"The Scottish parliament has demonstrated competent government and it represents a Scottish people who are wedded to a social democratic agenda and the kind of political values which sustained and were embedded in the welfare state of the late 1940s and 1950s.

"It is the Scots who have succeeded most in preserving the British idea of fairness and compassion in terms of state support and intervention. Ironically, it is England, since the 1980s, which has embarked on a separate journey."

He also analysed the progress of the Union since its birth in 1707 and the reasons why it had worked for both countries, but why he believes it is coming to a natural end. "The union of England and Scotland was not a marriage based on love. It was a marriage of convenience. It was pragmatic. From the 1750s down to the 1980s there was stability in the relationship. Now, all the primary foundations of that stability have gone or been massively diluted."

Devine received a knighthood in this year's birthday honours list for "services to the study of Scottish history". One newspaper wrote: "He is as close to a national bard as the nation has."

Devine is the author of 34 books and holder of all three of Scotland's most coveted prizes for Scottish historical research. His analysis of the issues at play in the independence campaign is forensic. "We now have a proper modern history of Scotland which we didn't have until as late as the 1980s. We have a clear national narrative underpinned by objective and rigorous academic research. This wasn't always the case."

Devine also points to what he calls the "silent transformation of the Scottish economy", based on the metamorphosis in manufacturing from heavy industry through de-industrialisation to a more diversified model. "Our economy is now based on some heavy industry, light manufacturing, electronics, tourism, financial services and a vibrant public sector which provides sustainable jobs.

"We have a resilient economic system and reserves of one of the most important things for an independent estate: power, power through the assets of oil and also through the potential of wind energy. In this, Scotland is disproportionately endowed compared to almost all other European countries."

Devine, who is from a working-class family of Irish immigrants, is fiercely proud of his ethnicity. It is a theme that informs much of his research and figures prominently in his writing. He believes the emancipation of the Catholic Irish in Scotland has also contributed greatly to a more robust economic model. He is scathing about the views espoused by George Galloway and some others that Catholics in Scotland would become more vulnerable in a smaller country. "This is nonsense. George, as usual, is talking rhetoric. None of those assertions is based on any academic understanding or knowledge."

He also cites the enhanced reputation of Scottish higher education and research, with four Scottish universities among the world's top 200. "We get 16% of the UK's competitive funding despite having only 10% of its population. If we can apply this research to industry and the economy, Scotland will have a head start in the future which will all be about brain-intensive industry. That adds to the potential resilience of the economy."

He now says "devo-max" would merely prolong a running sore. "If more powers are granted, many English people will be unhappy; they're already unhappy about the Barnett formula. Only through sovereignty can we develop a truly amicable and equal relationship with our great southern neighbour."

Devine believes the union served an important purpose and has now simply run its course. He believed it united citizens on either side of the border from the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 until the dawn of Thatcherism and that the cornerstone of the union and its main pillars have either crumbled or become rotten.

He cited the loss of empire and the dilution of Protestantism as a unionist ideology and the primacy of European markets over English and imperial ones. The loss of 12 Scottish regiments since 1957 had loosened military ties," he said.

"There's also the weakening influence of the monarch and the absence of an external and potentially hostile force which once would have induced internal collective solidarity, such as fascism and the Soviet empire.

"When you put all of these together, there's very little left in the union except sentiment, history and family."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion