The United Nations has spoken, 15 months after it was taken to court by 5,000 Haitians who blame it for bringing cholera to a country that remained unaffected by the three great cholera epidemics that raged in the Caribbean in the nineteenth century.

But nothing that the UN said pleased anyone and a protracted lawsuit and months, perhaps years of wrangling are likely over the victims’ families’ claim to a minimum of 100,000 dollars for each death.

Infection

While that plays out, Haiti cannot wait to become healthy and whole again. For Haiti’s overall well-being, it might be more useful to examine the truth of the UN’s pronouncement that “a confluence of circumstances” was responsible for the 28-month cholera epidemic, which has left nearly 8,000 people dead.

Haiti Cholera Outbreak. Demotix/ Jean Jacques Augustin. All rights reserved.

So, what is the truth? First, a recap of the arguments in an intensely sensitive matter, which pits a powerful international organization against vulnerable people in the poorest country in the Americas:

- The UN has offered equal parts of sympathy, empathy and apathy. It regrets that Haiti is infected with cholera after more than a century of being free of the disease; it points to the cholera eradication measures it is putting in place in Haiti and it flatly rejects all financial claims.

- The lawyers who took the UN to court on behalf of the Haitian people counter with scientific evidence that sourced the cholera strain to a less-than-sanitary military barracks occupied by UN peacekeepers from cholera-endemic Nepal. “If this had been a corporation and if it had been an environmental spill, there would have been liability,” says Nicole Phillips, a lawyer with the human rights firm Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI) in Port-au-Prince. Philips should know. She combines the compensation-for-cholera campaign with work on Haiti programmes at the University of San Francisco’s Centre for Law and Global Justice.

- Maximilien Saint Juste, 29, an electrician at a hospital in Saint Marc in Haiti’s worst-affected Artibonite region, says he’s been treated for cholera but still suffers "discrimination" for having once had the disease. "I think every victim should get compensation. The UN hasn't taken responsibility for the fact that they brought cholera to Haiti. Many people died from cholera and many of us suffer discrimination. A lot of (Haitian) people think that cholera cannot be treated entirely; they believe that cholera always sticks in your blood cells."

Médecins San Frontieres struggles against Cholera in Haiti. Demotix/ Jose Guzman. All rights reserved.

Leave the case to the courts; Haiti must have a different set of priorities. These must start with one self-evident truth and one salient question. It’s self-evident that Haiti had a full-blown cholera epidemic, while other countries in the region (the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Puerto Rico and Jamaica) had just a few, isolated, quickly contained cholera cases. So, here’s the salient question: Why?

“In Haiti, the cholera bacterium has fallen on fertile soil,” explains Dr Richard Cash of the Harvard School of Public Health. “If the same scenario with the UN had happened in Cuba, not Haiti, there would have been just a couple of cases.” He is referring, of course, to Cuba’s widely praised universal healthcare service and to the appalling lack of access to sanitation in Haiti (about half of its 10 million people have no bathroom at all). According to some estimates, even before the devastating January 2010 earthquake, only 12 per cent of the population received treated tap water and just 17 per cent had access to adequate sanitation.

Cash’s opinion counts for a lot. He is one of the world’s acknowledged experts on cholera and diarrhoeal disease and his leadership in the development and dissemination of Oral Rehydration Therapy as a practical treatment is estimated to have saved at least 50 million lives worldwide.

Deborah Jenson of Duke University reaches 200 years into the past to illustrate the salient truth of Cash’s point. Jenson, who co-authored a scholarly eponymous study on cholera in Haiti and other Caribbean regions in the nineteenth century, points out that in that age, “stories of cholera passing from contaminated ship laundry to laundering businesses in port cities were legion; today, something as simple as washing machines are part of the invisible barriers to the spread of epidemics.”

Jenson is, of course, making a salient point of her own. She says that “cholera is one of the diseases that medicine, sanitation systems, and technology have dealt with remarkably effectively…and the movement of UN troops, perhaps previously screened for cholera, from areas with active cholera in Nepal, to a poorly engineered barracks on the banks of a major river in Haiti in 2010, remains an example of a rare productive confluence of disease-friendly factors.”

‘Confluence’. There’s that word again. The UN would probably feel vindicated, but it’s important to note that Jenson is being professorial, not partisan. She concludes that the transmission of cholera to Haiti “should remain a significant lesson that no matter how rare, such transmissions can occur, and improved sanitary engineering and health care access remain the only firm barriers against such public health tragedies.”

Isolation

Or else, Haiti could try relative isolation, as in the nineteenth century, soon after it won independence from France? Jenson points out that one of the important reasons it remained disease-free, even as countries around it sickened with cholera, was its lack of “colonial army housing and slave barracks, since both the colonial military presence and slavery had been abolished and these were the environments in which cholera spread most effectively in the nineteenth century Caribbean.” At the time, Haiti, the world’s first independent black republic and only the second country after the United States to throw off the yoke of colonialism, was not completely isolated from the world. But it was isolated enough for reasons that had a lot to do with geo-politics and the economics of foreign policy.

This effectively meant that the Caribbean’s three cholera pandemics entirely bypassed Haiti, even though it was the largest and most densely populated country in the region and a near neighbour of the hard-hit Cuba and Jamaica. As Jenson records in her paper, “journalistic coverage in Haiti of cholera epidemics elsewhere in the official paper La Feuille du Commerce make it unlikely that epidemic cholera occurred there but went undocumented.”

Isolation has long been recognized as one of the best ways to prevent the spread of communicable disease. The very word ‘quarantine’ originates from the 40-day isolation period for ships and people in fourteenth-century Europe as it sought to prevent the further spread of the deadly Black Death. In the nineteenth century, Haiti itself was proactive in quarantine measures, right after the first reports of cholera in the region.

That was then. Isolation no longer seems to work so well in the twenty-first century, as was evident from the global effort back in 2003 to contain Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome or SARS. In the age of global travel, it suddenly seemed hopelessly mediaeval, not to mention hideously impractical, to restrain the movement of people to prevent the spread of infectious disease.

Global movement is an important concern for a country like Haiti, impoverished, tumultuous and tragedy-scarred, and now seeking to market itself anew to the world as a tourist destination.

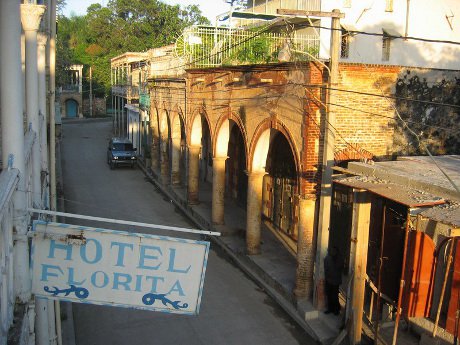

Travels in Haiti. Demotix/ Daniel Metcalfe. All rights reserved.

In the twenty-first century, Haiti cannot try isolation to prevent infection. The only frontline against diseases such as cholera, stresses Richard Cash, is water sanitation and other sanitation efforts. “The Haitians, particularly their government, must be responsible for that. Of course, they should be helped, by the UN, by the world, but primarily, it is their responsibility. And that is their defense against disease because anyone can carry cholera, but it doesn’t have to become an epidemic.”

Lawyer Nicole Phillips challenges the basis for this “Blaming the Haitian government for cholera is like blaming the wind for a forest fire in a drought after you light a match. You can blame the wind for the fire, but you lit the match.”

The blame-and-shame argument will continue but it is at least important to recognize that in an increasingly interconnected world, globalization can literally kill if the very basics – sanitation and clean water – remain a distant aspiration. And one that depends on the eventual outcome of a lawsuit in a faraway court.

For Haiti, as with everywhere else, the frontline of the fight against disease always lies at home.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.