The public clash between Hachette and Amazon has been making headlines for a while now, most recently around J K Rowling’s latest novel. Amazon bowed to consumer pressure after complaints that the book was being offered by the site as “usually ship[ping] within 1 to 2 months” – on the first day of its publication.

At the heart of the dispute is the question of who controls the prices of e-books: should it be the retailer (Amazon) or the publisher (Hachette)? Many ask if it’s healthy for Amazon to use its formidable power to leverage huge discounts from publishers in order to increase its market share in book retailing. Restricting the right of publishers to set their own prices perhaps threatens an already fragile industry even further, stifling innovation and risk-taking in the book market.

On the face of it, the greater the discount Amazon receives, the cheaper the book costs readers. And this is precisely the position that Amazon is adopting, arguing that the primary beneficiaries of its victories over the publishers are us, the consumers.

At the same time, Amazon stands accused of obstructing customers’ access to Hachette titles (both print and digital) on its website, thereby limiting our own freedom to access the books we want to read. Industry pundits are debating the implications of vesting so much control in a single global entity, which can pick and choose whose products it makes available to whom.

Only slightly less vocally, Apple has itself been counting the cost of moving into e-book publishing. In July 2013, the US Department of Justice won an anti-trust suit against Apple and five publishing giants for collusion in fixing prices to undermine Amazon’s 90% share in the e-book market. Two years’ of legal wrangling with the DoJ recently resulted in an undisclosed out-of-court settlement between the firm and all 50 states, avoiding a trial in which Apple could have faced as much as $840m in claims.

And if publishing new books weren’t enough trouble, another tech giant has been in hot water over making old books available online. A long-running conflict between Google’s digital Library Project and the Association of American Publishers and the Author’s Guild was finally settled after eight years’ litigation, ruled in Google’s favour last November.

These clashes between the old publishing Titans and the new tech Olympians strongly demonstrate that the market, while healthy, is nevertheless undergoing a fundamental reorientation. And this will force us to rethink the role of books in society: as conduits to learning, as objects of entertainment and as economic products.

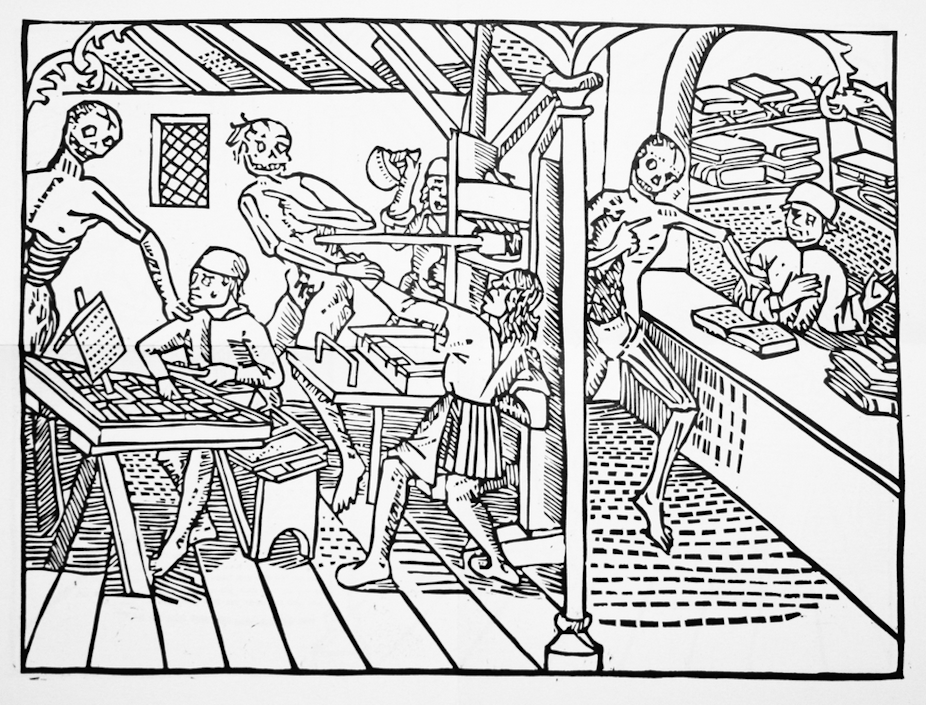

The birth and death of print

When Johannes Gutenberg pioneered the moveable-type printing press in Western Europe in the 1450s, his intention wasn’t to revolutionise the practice of book production. In fact, Gutenberg’s early printed works, such as his famous Bible, deliberately mimicked the appearance of the manuscripts that they were destined ultimately to displace. The shift in Europe from a manuscript to a print culture was a relatively slow one, taking nearly a century to accomplish.

Living through our own period of transformation, from the age of print to a new digital era, it’s easy to feel caught in the grip of a revolution that has changed the last half-millennium of textual communication almost overnight. Today’s major platforms for textual communication: emails, the internet, smartphones, tablets, e-readers, were the stuff of science fiction just a few decades ago.

And nowhere have the implications of this shift from print to digital formats been more vocally expressed than in the ongoing debate about the future of the book.

As early as 1994 the death knell of print was being sounded in Sven Birkerts’s The Gutenberg Elegies, while back in 2007 Jeff Gomez told us unambiguously that Print is Dead. And yet, the printed book remains a ubiquitous presence in our supermarkets, our libraries and our bookshelves, healthily outliving its predicted demise.

Print is maintaining its tenacious hold on our reading practises. A recent survey by the Pew Research Center found that 52% of Americans are reading only printed books, while just 4% read e-books exclusively.

Nonetheless, the recent high-profile events surrounding Amazon, Apple and Google have demonstrated just how fragile the world of publishing is. Traditional safeguards that regulated print publishing seem more vulnerable in the wake of the take-up of e-book readers by consumers.

Shifting sands

In such uncertain times, publishers are responding in intriguing, radical ways – most evident in the £2.4 billion merger of Penguin and Random House last summer. This will deliver the joint venture 27% of the UK market, and is itself no doubt being scrutinised by competition authorities.

As John B Thompson notes in his thorough study of the modern Anglo-American publishing industry, Merchants of Culture (2012):

The delivery of content in digital formats could, at least in principle, enable the creative industries to eliminate or reduce some of the long-standing inefficiencies associated with traditional supply chains. But at the same time, it carries the risk – by no means hypothetical, as the music industry shows – that content becomes cannon fodder for large and powerful technology companies and retailers.

So in fact, the picture is far from gloomy. The digital revolution has unlocked an entire new field of production to self-publishing authors and independent publishers. All of them would have been unable to enter the literary marketplace were it not for the internet and new platforms available for consuming books. The most (in)famous example of this is that of E L James’s Fifty Shades of Grey trilogy, which became the fastest-selling paperback in history, transcending its origins as Twilight fan-fiction and building on the series’s phenomenal early success in e-book format.

While James’s success is hardly representative, it points to a much more complex set of dynamics in the publishing world. E-books have not yet made printed ones obsolete: as in James’s case, they can actually stimulate demand for them. But what’s happening is that modes of consuming media are converging, rendering boundaries increasingly elastic – as pioneering studies by scholars such as Henry Jenkins have shown. I can now purchase a book from Amazon over the internet, start reading it on my Kindle, pick up where I left off on my iPhone on the bus and share my thoughts about it with other readers on social sites like Goodreads when I get home.

And this convergent, interactive world of reading is mirrored by creative approaches to the future of the book that bring together the intimate experience of reading with new digital technologies. This is leading to radical ways of re-conceiving the concept of the book.

This bridging of the print and digital worlds suggests that the future of the book may not merely involve replacing the page with the screen. It will almost certainly reshape our understanding of what “books” and “readers” mean, let alone what role publishers might play. In light of these transformations, the stakes involved in the clash between Amazon and Hachette may be higher than we realise.