The events of the last several months have proven that all existing mechanisms and arrangements to provide for Ukraine’s security have been ineffective. The country has found itself in limbo, desperately trying (and often failing) to provide for its own security while defending against Russian aggression.

There is no doubt that corruption, incompetence, and negligence have prevailed in Ukraine across many domains, including national security and defence. Military reform has been ineffective. Military appropriations have been inadequate, with funds often simply not reaching the intended parties. Public oversight has been non-existent, while the social status of the military, and the level of public appreciation for it have been low (if rising in recent months). Such circumstances have not encouraged the best and brightest to join the ranks.

Ukraine has a number of security options to consider. Photo (c): Ilya Vasyunin

Ukraine was basically a ‘disarmed’ state.

Viktor Yanukovych’s rule, in particular, was damaging for the Ukrainian military as with most sectors in the country. For whatever reason, Ukraine was basically a ‘disarmed’ state.

What lessons can we draw from Ukraine’s state of affairs in the current conflict with Russia, not just for the Ukrainian military but also in terms of broader security arrangements for Ukraine? What options exist?

Maintaining the status quo

This is a well-travelled path for Ukraine, which for years has avoided any comprehensive risk assessments of the status quo. That Russia would directly intervene was a scenario that Kyiv believed was extreme and unrealistic. There is no doubt that even with better preparation, it would have been a daunting task to withstand Russian intervention. Nonetheless, preparing contingency plans coupled with appropriate diplomatic activity is a core part of a government’s mandate, and may have better prepared Ukraine for its current circumstances.

That Russia would directly intervene was a scenario that Kyiv believed was extreme and unrealistic.

Ukrainian decision-makers, always preoccupied with their petty political and financial struggles, neglected existential threats and worst-case forecasting. They have always viewed the ‘Ukrainian independence project’ as a way to personally enrich themselves and advance the interests of their own networks, rather than take care of national interests, nurture the nation-state, and prepare for possible threats.

Diplomatically, Kyiv has rested comfortably, believing that certain international agreements would provide for Ukraine’s protection. The 1994 Budapest Memorandum is a perfect example of this. Ukraine did not receive clear and concrete security guarantees when the memorandum was signed but only muted security assurances. For years, Ukrainian security experts have tried to draw attention to the fact that the assurances in the memorandum are vague and unreliable, underlining that only by actually joining the Euro-Atlantic security system could Ukraine receive adequate protection against potential threats.

It should not have come as a complete surprise then that the Russian Federation blatantly violated the Budapest Memorandum. Ukraine’s dealings with Russia have always been a difficult business. Time and again, Moscow’s words and even signatures have amounted to nothing. The other two signatories to the Budapest Memorandum – the United States and United Kingdom – look to have fulfilled their limited obligations. They have repeatedly highlighted Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in the international community (including the UN Security Council), and engaged in intensive consultations on the subject. Unfortunately, this is all that those ‘security assurances’ called on them to do.

The option of doing nothing should be discarded. It will doom Ukraine to more of the same troubles in the future. It will leave Ukraine fully defenceless and vulnerable, at the mercy of an aggressor.

Neutrality

‘Permanent neutrality’ or the ‘Finlandisation’ of Ukraine is often suggested today by the Kremlin, and even by some sincere well-wishers for Ukraine, who see it as the only way to save the country. To impose this ‘solution’ on Ukraine, instead of helping it withstand Russian aggression, is self-evidently bad policy.

First, even if an agreement on neutrality were concluded, Russia’s record on security guarantees for Ukraine suggests Russia would simply violate the agreement when it saw fit. Second, there would be no mechanism to enforce it – the logistics of such an arrangement are impossible to conceive. Third, it would be a final blow to international law and order, a win for the Kremlin (encouraging it again to act according to its current playbook); and a loss for the West, quite possibly leading toward the crash of meaningful Euro-Atlantic security cooperation. Finally, this would bring an end to the concept of state sovereignty. With Ukraine’s sovereignty violated and then limited, such a solution would not lead to greater stability. Ukraine would cease to be a subject of the international arena, and at the mercy of its more aggressive neighbour. Both its ‘autonomy’ and its ‘security’ would be gone.

What some proponents of ‘permanent neutrality’ tend to forget, or ignore, is that today’s context and circumstances are entirely different from those of Austria in the post-Second World War period or Finland throughout the Cold War; and Ukraine is not Switzerland. To advocate such an approach now would mean to doom both Ukraine’s security and the future regional and international order to failure.

Ukraine is not Switzerland.

Going it alone

Can Ukraine provide for its own security by drawing solely on its own resources and potential, without any international assistance or specific bilateral or multilateral arrangements? This is an idea that nationalists in various states often advocate. Ukrainian nationalists, while small in number and politically marginal, are not much different.

Such an arrangement might have a better chance of working against smaller-scale threats, but Ukraine’s conflict with Russia will always be asymmetrical, leaving it with a minimal chance to succeed against full-scale invasion. This option would also require the massive and permanent militarisation of Ukraine, which would be detrimental to democracy, human rights, the economy, and the social sector. The country is hardly capable of supporting such an effort at present, and it would not be a welcome scenario even in the distant future.

The nuclear option

Some consider the nuclear re-arming of Ukraine as an option. Given the circumstances, it is not surprising that this idea is floating around the country, and has gained some popularity, less among experts than in the public domain. Ukrainian nationalists, specifically within the Svoboda party, also invoke this idea. Svoboda performed poorly in the May 2014 presidential election, but there remains a chance that it can do better in upcoming parliamentary elections. In any event, the fact that the public likes the idea will probably lead to the issue remaining – at least rhetorically – on the political agenda.

But this is not a viable option, for Ukraine has already rid itself of nuclear weapons, and re-arming is both not feasible, and would in any case be ineffective. It would lead to greater instability for Ukraine and the entire region. It would not help against Russia for a variety of reasons, including its geographic proximity and Russia’s own vast nuclear arsenal.

Euro-Atlantic security integration

This option is for Ukraine to become part of the Euro-Atlantic security zone. It is considered by many to be the optimal and, in fact, only effective solution. Both theoretically and technically, it remains on the table. It is obvious, however, that the best time for a decisive move in this direction is in the past. Current circumstances are not conducive to reanimating efforts to bring Ukraine into NATO. Russian antagonism toward the idea has grown tremendously, and there is a clear lack of willingness to proceed on the part of many NATO members. The Ukrainian public remains divided on the subject, even though polls have revealed sizeable growth in support of the idea since Russia’s invasion. In the coming months, Ukrainian political elites might very well align themselves with this perspective.

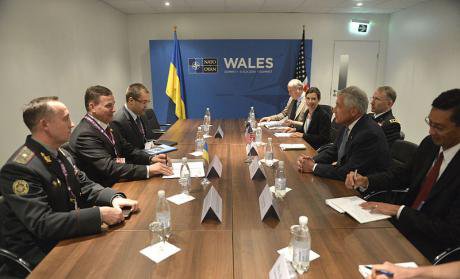

US Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel meets with Ukrainian military personnel at the NATO summit in Wales. Photo CC: Glenn Fawcet

The best time for a decisive move in this direction is in the past.

That said, apart from the issue of membership (which is still possible in accordance with the decision made at NATO’s 2008 Bucharest summit, its strategic concept, and other guiding documents), more cooperation between Ukraine and NATO ought to exist. The Alliance should realise that Ukraine is fighting for exactly the values and principles on which the Euro-Atlantic process is based – a stable international order, territorial integrity, human rights, and a more democratic political system. NATO should be capable of learning from this crisis, and more ably adjust itself to face similar current and future threats and challenges. There is a chance for NATO to be a stronger regional actor. If it does so, Ukraine will be a natural ally.

US-Ukraine partnership

Finally, a bilateral security partnership with a willing United States is another option. For this to be successful it would require a long-term American readiness to devote resources and energy to Ukraine, which would include a clear understanding of why this is in the interests of the United States. If the Ukraine crisis continues to escalate, this scenario could become less a matter of choice for Washington than one of necessity. But on Ukraine’s part, such an arrangement would also require much. Kyiv would have to eradicate corruption and bad governance, and stay on a democratic path. Unlike ‘permanent neutrality,’ this would not entail undermining Ukraine’s sovereignty, however, as it is an option that would not be imposed upon Ukraine. It is an option that would make Ukraine stronger and more capable of handling military aggression with confidence. The ‘Russian Aggression Prevention Act of 2014’ which was introduced to Congress earlier this year, that proposed non-NATO ally status be granted to Ukraine (and Georgia and Moldova) can be seen as a step towards that very option.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.