Backstage at the V&A Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green, east London, Jacqueline Wilson is peering at a photograph. "Ah, yes," she says, politely feigning a click of recognition. "This is my childhood bedroom – or at least, a copy of it. Of course, if a girl's lucky enough to have her own room nowadays, she's likely to decorate it her own way. But mine was brown, and there isn't a little girl in the whole world who would have chosen that. I had a hand-me-down ottoman from my grandmother that was brown, and my mother bought me an eiderdown to match, and a second-hand chest of drawers that wouldn't open and close properly." She brightens. "It wasn't all bad, though. I had my dolls, and my Margaret Tarrant fairy pictures on the wall and, as you can see, my books, and it meant a great deal to me. It was a place to be private, to play my own games, to mutter at my imaginary friends without one of my parents telling me to be quiet."

This 1950s room, so austere that just looking at it could bring on a bad case of chilblains, will take centre stage at the museum's forthcoming exhibition about Wilson and her world – a reconstruction achieved by curators thanks largely to eBay. Wilson, whose idea this installation was, felt that while adult visitors would be perfectly happy to gaze on manuscripts of her books, children would require a more hands-on experience. How, though, does looking at the result make her feel? "It's very odd. They've gone to such pains to get it to look exactly as it did." A childhood friend who saw the room when the exhibition was first staged at Seven Stories National Centre for Children's Books in Newcastle insisted the curators had got some details quite wrong. But I doubt she was right about this, and Wilson looks equally sceptical. One has only to read a few pages of Jacky Daydream, the autobiography she published in 2007, to know that she has peculiar recall when it comes to the past. I can think of no other writer – no other person – who's able to remember their primary school days in such Technicolor detail; every doll, every book, every ill-fated trip to Clacton with her parents (they "hissed" insults at each other over breakfast; she felt "bilious"; the hotel's talent night, at which she performed a poem by AA Milne and promptly wet her knickers, was an event to be dreaded).

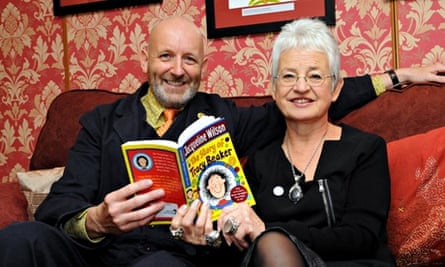

On this damp morning, the former children's laureate is wearing witchy shoes – they're heeled, black lace-ups, and the leather has a brocade pattern on it that pleases her mightily – and a tufty coat; she rocks a kind of punk-granny look. Technically, Wilson is in poor health – she was fitted with a heart defibrillator some years ago and is now on the list for a kidney transplant – but you would never know this to be the case from her manner (she says her thrice-weekly dialysis sessions have increased her energy, if anything). Friendly and professional, her answers to questions are extremely long and detailed; she's one of those precise people who dislikes leaving anything out.

"I do enjoy my job," she tells me more than once, a statement with which no child who has ever encountered her would be inclined to disagree. Wilson is adept at spreading herself around, but this, you soon realise, is a skill born of the fact that Britain's biggest-selling children's author – 30m copies and rising – would meet every single one of her fans in person if only it were possible.

"I used to be so proud of saying I answered every letter myself. I used to do drawings, and it was all quite elaborate. But it became too difficult, a full-time job in itself. I still read them all, but I only answer the ones that are particularly touching, or which are from children who are worried or ill."

We look at more material from the exhibition: a first draft of Tracy Beaker, the character that made her name; a picture of Mandy Miller, the child star with whom, as a girl, Wilson was obsessed ("I had my photograph taken with her in Battersea Park when I was 11; I was trembling, and that makes me so understanding now when girls go all shy and their mums have to prod them"); some drawings by Nick Sharratt, her long-time illustrator and close friend (they holiday together every year, visiting Landmark Trust properties where they wonder how lavishly to decorate the visitors' book).

And then, finally, the item I have most been looking forward to discussing: a page from Jackie magazine, on which Wilson once worked. "That's me pretending to be Patricia somebody-or-other," she says, pointing at a photograph which illustrates an article entitled: "Going Steady: is it the Same as Being Engaged?" I tell her that my mother once banned me from reading Jackie, with the result that even now – I'm 44, and it is long defunct – it has a powerful allure for me.

She frowns. "It was very moral so far as I remember," she says. "It suggested waiting. They took Cathy and Claire [the magazine's agony aunts] very seriously. A qualified team had to answer those, and we were never allowed to see the letters."

But we're getting ahead of ourselves. The Jacqueline Wilson story does not begin in the offices of DC Thomson (the owner of Jackie) in Dundee, but in Kingston, Surrey, where she grew up and still lives to this day. Her father, Harry, was a draughtsman and later a civil servant, and her mother, Biddy, was a clerical worker; Wilson was an only child, which meant she had to cope with their rows alone. "They married three months after they met. Nowadays, they would just have had a brief fling and that would have been it, but things were different then; it was a mad time, during the war. I don't think either of them wanted to stay in the marriage, but divorce was quite scandalous, and my mother wouldn't have had the means to support me even if she had left. So they stuck it out. They weren't cruel, but it wasn't a happy, cosy family."

In Jacky Daydream, Wilson is strikingly cool towards her parents, often chiding them for their lack of patience and only rarely making the effort to see things from their side (her sympathy is always with the child, and that includes, in this book, herself). But today, she is a little more generous, damning them only with faint praise. "It was a wonderful environment for the writer who wants to write the sort of books I do."

A bright, bookish child, she passed her 11-plus on her second go. But university was never a prospect, and she left school at 16. "I wasn't from the kind of background where you automatically went on to university, and, in any case, I didn't particularly like school. My parents told me I had to be able to earn a living, so they sent me to a technical college where I learned shorthand and typing, which I found a bit grim."

When the course finished, she began looking for jobs in the small ads of the London Evening Standard, and it was there that she saw the three words that would change her life: WANTED – TEENAGE WRITERS. "With extraordinary confidence," she says, "I wrote a humorous article about what it's like to go to your first dance, and how embarrassing it is if no one is interested in you, and all the little ploys you could use to pretend you were enjoying yourself, and sent it off to DC Thomson. I remember exactly how much I was paid for it: three guineas. I didn't have a bank account, and my father had to cash the cheque for me." Encouraged, she now began to bombard the company with more articles, and eventually was asked if she wouldn't like to come up to Scotland to work for it. "I thought this would be my one opportunity, so off I went. I was going to be working on an as-yet-unnamed teenage magazine, but I'd also get experience on other titles: Red Letter, Annabel. On Thomson's part, it was a shrewd move. I was paid a weekly salary; they no longer had to pay for all the articles I wrote."

She arrived on the sleeper from London, and headed to the Church of Scotland Girls' Hostel that would be her new home, only to discover there had been a misunderstanding over her booking. "It was completely full: bedrooms, cubicles, dormitories. But when I looked as though I was about to burst into tears, the matron took pity on me and gave me the linen cupboard. There was a camp bed, and she moved some of the sheets and towels so I had a place to put my things. I was there for three months, and it was wonderful. It was the only warm room in the hostel, which meant that the other girls wanted to be my friend whether they liked me or not; we would all squeeze up together."

At the weekends, however, most of these girls returned to their parents in the country, leaving Wilson alone. "Even cook went home. She would leave sandwiches in the fridge for me. When I was really homesick, I wandered round Woolworth's, which looked and smelled exactly the same as the one at home."

Is it true that DC Thomson named Jackie after her? "The men in charge were Mr Cuthbert and Mr Tate, and on Friday mornings I had to take them their coffee and give them a report of what I'd been doing. On one of these mornings they told me they'd named it after me, and I was charmed. But later on, someone else said it had been nothing to do with me: the name was in the air, thanks to Jackie O."

Still, it's a good story, and one she likes to bring out at events. "The mums always go: 'Oh my God.' Every girl read Jackie, or wanted to, and that went across the board, class-wise."

Back at the hostel, Wilson made sure she bagged herself a boyfriend as quickly as possible – at least she'd have somewhere to go for Sunday lunch – and it wasn't too long before she was engaged to Miller, a DC Thomson printer. Together, they moved south. But printing was then still heavily unionised and Thomson was a non-union company, with the result that he could get no work. "So he became a policeman, which he enjoyed. He rose to be a chief superintendent."

Did she enjoy being a policeman's wife? "No, I hated it. We lived in police flats for a while, and I didn't like being part of that community. I felt out of my element." She sighs. "My husband was very sporty and I hate sport, and he'd never read a book in his life and, for me, reading is everything. I suppose you could say I repeated my parents' marriage. I suppose you could say I was lonely, and here was this chap who made a bit of a fuss of me."

Nevertheless, the marriage lasted for almost 40 years (they were divorced in 2004). "A lot of the time, we got on OK, and we had our gorgeous daughter, Emma, who is so special. When it ended, it took me very much by surprise. It was classic: he'd been having an affair, and I didn't know. But it also came at the right time. Our daughter had grown up and by then I was earning a reasonable amount. I knew I could support myself. So I threw myself into my job, trudging all over the country and keeping busy. Getting older doesn't have much going for it, but you do think: 'Well, this is me now,' and you can surprise yourself."

Down the years, Wilson had never stopped writing; when her daughter was small, she wrote three anonymous "confessions" stories a week for Loving and True Romance (she used to make them as long as possible because the owners paid per 1,000 words, and it's thanks to this, she believes, that she never suffers from writers' block). Her first three books were crime stories for adults, but each of them had among its more prominent characters a child, and she soon knew that it was for children that she really wanted to write. She remembers very well the thrill of her first advance for a children's book – and she remembers, too, the satisfaction she felt when her novels finally began to "earn out" (in other words, when she began to be paid royalties on top of her advance), a change that came about largely thanks to Tracy Beaker. But what a wait she had: The Story of Tracy Beaker wasn't published until 1991, by which time she'd been publishing for two decades, and its heroine didn't become a household name until the BBC made a series based on her in 2002.

Wilson got the idea for Tracy Beaker after seeing ads for foster carers in local news-papers, most of which were accompanied by a photograph of a child. "I thought: how must it feel to be advertised like this? What if no one notices you, or someone else in your children's home gets lots of people coming forward and you don't? A close friend worked in social services and she told me that children in care get given a scrapbook to fill in, and then I had it: this was how I would start the book. Tracy is a difficult girl, and she messes around, and she writes things in the margin, and she doesn't always tell the truth. I found it lovely to write Tracy once I had her voice; she introduces children to the idea of the unreliable narrator."

Tracy used to be Wilson's most popular character by a mile, but, lately, Hetty Feather, a Victorian foundling, has begun to nose ahead (at the Museum of Childhood, a whole room will be devoted to her). Next up will be a new character, Opal Plumstead, an Edwardian heroine who ends up working in a sweet factory, and who will provide Wilson with an opportunity to touch on suffrage. How many books has she written by now? Oh, only about 100.

It's not just writing to which she's addicted, though. At her Victorian house in Kingston, the books are slowly taking over, in spite of the fact that she has a small library at the bottom of her garden (it used to be a dentist's consulting room). "I find it very difficult to get rid of books," she says. "Once or twice, when I've been very poor, I've sold a few, but as soon as I had the money I went back to the second-hand bookshop and bought them again." At least dialysis provides an opportunity for reading, and she has just devoured for the second time all of Elizabeth Jane Howard's Cazalet Chronicles.

As you would expect, Wilson regards the closure of so many of our libraries as "sad and terrible"; she couldn't have got by without the library as a child and, later, as a young mother (these days, of course, she is the decade's most borrowed author). But this doesn't mean that she worries about reading itself, at least not among younger children. The schools she visits seem be to full of book-loving girls and boys – and she's adept at working out whether they've been primed beforehand. What about teenagers? This is more difficult. She doesn't write for them because she lacks confidence. "Social networking, girls being so intensely interested in the way they look… I struggle to get into that mindset. When they're at primary school I'm there with them. But then they go off into this world where adults aren't welcome anyway."

I can't pretend to be able to explain Wilson's deep and abiding connection with younger children, particularly girls, and it's slightly baffling to hear that some send her photographs of themselves dressed up as "Jacqueline Wilson". Clearly, she understands their concerns, which are always the same wherever in the world they happen to be. She also, unlike certain other famous children's authors of the past, seems actually to like children. But I think, too, that some small part of her will always be there in her childhood bedroom, getting lost in a favourite book – probably a tale of two orphans called Nancy and Plum – or weaving stories around her beloved dolls; according to Jacky Daydream, there are some she misses even now. And perhaps it's this that is the key to her success. For all her warmth, she talks to me slightly at a distance. I half wonder if I shouldn't have sent my eldest niece along to interview her – a girl every bit as nosy as me, and many, many years my junior.

Daydreams and Diaries: The Story of Jacqueline Wilson is at the V&A Museum of Childhood from 5 April to 2 November (museumofchildhood.org.uk)

The UK tour of Hetty Feather opens at the Kingston Rose Theatre on 5 April. For further tour information, visit hettyfeatherlive.com

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion