Some people associate crosswords with respectability: the suburbanite knocking off the Times on the 7.22 from Twyford, or the major's wife tidying away her coffee morning and settling in to the Telegraph.

It wasn't like that when they first appeared. Imagine a new video game called Benefit Cheat which comes in a box with a week's supply of meow meow, picture the likely response from the mid-market tabloids, and you'll have a sense of how crosswords were welcomed in Britain.

The British Library's new online newspaper archive lets solvers have a look at the 1920s, and feel that if they'd been around then, they'd have been considered a little bad-ass.

Part of the concern seemed to be the speed at which crosswords were catching on. How speedy are we talking? "The cross-word puzzle mania is becoming more hectic even than craze for 'put and take'," notes the Nottingham Evening Post in 1925. (Yes, you do. Sort of a dice shaped like a little spinning top.) And for the effects of this hectic craze, we only need to look to America.

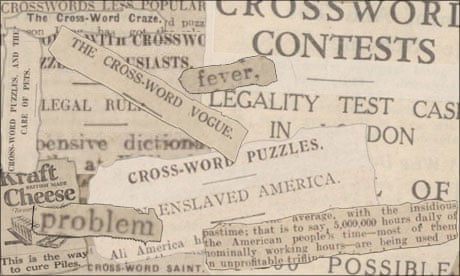

The papers had for a while been terrifying readers with tales of the mayhem wreaked by crosswords across the Atlantic. "CROSS-WORD PUZZLES. AN ENSLAVED AMERICA", howls the Tamworth Herald in 1924. The crossword, the piece explains, "has grown from the pastime of a few ingenious idlers into a national institution: a menace because it is making devastating inroads on the working hours of every rank of society."

Everywhere, at any hour of the day, people can be seen quite shamelessly poring over the checker-board diagrams, cudgelling their brains for a four-letter word meaning "molten rock" or a six-letter word meaning "idler," or what not: in trains and trams, or omnibuses, in subways, in private offices and counting-rooms, in factories and homes, and even - although as yet rarely - with hymnals for camouflage, in church.

These pernicious puzzles, the Herald goes on, "have dealt the final blow to the art of conversation, and have been known to break up homes." This family-wrecking comes about when husbands spend time solving a clue rather than earning a crust:

Twice within the past week or so there have been reports of police magistrates sternly rationing addicts to three puzzles a day, with an alternative of ten days in the workhouse.

A 1924 Reuters report contains a further warning from Canada - "Cross-word puzzles and the radio have been given as the reason for a marked decline during recent months in the demand for books at the Ottawa public library" - but this is nothing compared to what's to come to the UK. "The damage caused to dictionaries in the library at Wimbledon by people doing cross-word puzzle," we read in 1925, "has been so great that the committee has withdrawn all the volumes." In Willesden, it's the same sad story. Dulwich Library, meanwhile, starts blacking out crosswords' white squares "with a heavy pencil, to prevent any one person from keeping a newspaper for more than a reasonable length of time." Selfish paper-hogging solvers.

Meanwhile, booksellers bemoan falling sales of the novel - no longer itself considered a menace to society - in favour of "dictionaries, glossaries, dictionaries of synonyms, &c.". The Nottingham Evening Post goes on:

The picture theatres are also complaining that cross-words keep people at home. They get immersed in a problem and forget all about Gloria Swanson, Lilian Gish, and the other stars of the film constellation.

It gets worse. Also in Nottingham, the zookeeper is getting swamped in correspondence. The reason? Crosswords, of course.

Correspondents [are] unabashed over requests for aid in solving "cross-word" puzzles, and the Zoo at least will be relieved when a new hobby takes the place of the current one. What is a word three letters meaning a female swan? What is a female kangaroo, or a fragile creature in six letters ending in TO?

Across town at the theatre, the stage is bare:

Mr. Matheson Lang... missed his entrance in the Inquisition scene through becoming absorbed in a puzzle. This caused him much chagrin, for he is extremely conscientious as regards his stage work.

All the "Wandering Jew" company at the New Theatre are, like their chief, interested in cross-word puzzles.

Who is safe from this funk? Surely the world of grocery is unblighted? Sadly not:

A girl asked a busy grocer to name the different brands of flour he kept.

When he had done so, expecting a sale, she said she didn't want to buy any. She just thought one of the names might fit into a cross-word puzzle she was doing.

The cross-word craze has been described as a disease. For which the scientific name might be "cluemonia."

If you find "cluemonia" comical, wait until you read the whimsical the Village Philosophy column in the Western Times, a kind of 1920s Karl Pilkington:

This week us 'ad a bit of talk about those yer crossword puzzles as they calls 'm. I duunaw that I knaws rightly what they is, 'cause seems to me they'm mostly for the bettermost people what got time to spare...

I got a [daughter] only her don't ask me no questions. Her's fiddling about most all the week about what don't seem to be no use to nobody. Her send in to the competitions [but] her never won nothing yet, and I don't s'pose her's ever likely to."

And this aspect of "cross-words" - the competition - adds to the alarm. A 1925 Western Times think piece begins:

One of the most marked characteristics of this present century is the competition fever, which holds a big proportion of the population under its allurement. The root of the whole problem can be found in mankind's instinctive desire "to get something for nothing." It is not surprising, therefore, to find that many ingenious devices have been used to attract the attention of the public in this respect, and the latest method is known as the cross-word puzzle.

The time and energy spent on crosswords, the Times explains, would be more profitable "devoted to reading an instructive book, or intellectual conversation" - or, again, working. By the 1930s, the prizes offered for puzzles find crosswords in the courts with judges having to decide whether skill is involved or whether, as a lawyer for the police argues at Bow Street in 1935, "the words are ridiculously easy, and a child of 12 should have no difficulty in solving them". This would apparently mean that crosswords contravene the Betting and Lotteries Bill: literally, as well as morally criminal.

Judges, to the chagrin of police and moralisers, tend to find in favour of crosswords, putting them on a path to respectability also marked by an important announcement:

Eating our own words is a familiar phrase. Eating cross-words is a new pastime, but a pleasant one since Messrs. Huntley and Palmers, Ltd. have put on the market their "Cross-word" Cream Biscuit, so named because of its design. Simultaneously with arrival of the new biscuit Messrs. Huntley and Palmers have inaugurated a cross-word competition in which prizes are offered to the extent of £1,000.

Of course, the newspapers themselves had by now got in on the act, publishing crosswords and by some accounts relying on the puzzles for newsstand sales. Hypocrisy, following scaremongering and berating the British public for not toiling every hour God sends. Who'd have thought it from the press?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion