Essay by Will Smith

. . .

(courtesy of yossi milo)

Pieter Hugo first learned of Nigeria’s Gadawan Kura, or hyena handlers, in 2003 when he received an image taken on a cell phone camera depicting several of these men with their beasts in the streets of Lagos. A newspaper in Hugo’s native South Africa published a similar image and identified the men as debt collectors, drug dealers, and thieves who enlisted hyenas as muscle in support of their criminal activities. With the help of friends in Nigeria, Hugo found the group in a shantytown outside of the capital, Abuja. They were not necessarily criminals, but rather what Hugo describes in an artist’s statement as “itinerant minstrels... a group of men, a little girl, three hyenas, four monkeys and a few rock pythons,” who subsist by staging performances and selling traditional medicine. Hugo traveled with the group for weeks at a time over the course of two years, taking a series of portraits of the men posing with their animals.

Much of Hugo’s work documents life on the peripheries of African societies, addressing the complex political realities of race and identity through the conventions of portraiture. The circumscribed scope of the genre forces an engagement on the level of the individual, an approach that skirts both sentimentality and the journalistic impulse to explain. He has photographed inhabitants of border towns and civil war zones, farm workers, and migrants, in each case rendering social flux and marginalization with reference to the human face and figure.

In Hugo’s series on the Gadawan Kura, entitled “The Hyena and Other Men,” the subjects are also animals. The titles of the photographs include the names of both the humans and animals depicted along with a reference to the various cities in Nigeria where the images where taken. These double portraits describe a trans-species relationship unfolding in a setting of poverty and uncontrolled urbanization. They constitute a stark tableau of life on the margins, but also raise questions of how and to what extent this life can be something shared by human and non-human subjects.

Hyenas are startling animals. Though they can resemble predatory cats or large feral dogs, they comprise a unique species and occupy their own back alley of the animal kingdom. Spotted hyenas can weigh up to two hundred pounds with most of the weight distributed over a torso that slopes down at an angle towards the hind legs. This odd configuration gives the impression that the animal’s girth has been compressed forward into powerful front haunches and a thick, distended neck topped with a mohawk of fur. Hyenas’ heads support a disproportionately large jaw capable of crushing the bones and hooves of zebras. They can digest every part of an animal; in the wild, their feces are often white because of the large quantities of bone matter they consume.

(courtesy of yossi milo)

Determining a hyena’s gender can be a challenge. Females of the species are not only larger and more aggressive than males, but they also have an elongated clitoris that closely resembles a penis in size, shape and erectile ability. Lacking an external vagina, females urinate, mate, and give birth through this pseudo-penis, an anatomical anomaly that has fueled the popular misconception that hyenas are hermaphrodites.

Captivation does little to mitigate the hyena’s bizarre appearance. Historically, the animals have seldom been domesticated and seem only precariously so in Hugo’s photographs. The hyenas are bound with woven muzzles attached to chains that seem better suited to anchoring medium-sized boats than to leashing an animal. Some of the men are depicted with sticks or clubs, presumably as a counter-measure if the animal were to slip, for a moment, back into the wild. At the same time, the possibility of barely suppressed animal violence erupting is what makes the hyena a compelling spectacle—or an effective partner in crime.

Hyenas have played a role in human culture since the ancient Egyptians hunted them for food, but they have also long been a source of ambivalence within anthropocentric models of the natural world. We tend to overlay our own value systems onto animal behavior, allowing us to understand black labs as loyal friends and marginalize less adorable animals such as the hyena. Because they scavenge the leftovers of “noble hunters” like lions, hyenas have been portrayed in Western literature as timid or cowardly. Medieval bestiaries commonly use images of hyenas mating to warn against homosexuality, likely because of the female’s bizarre genitalia. In Edmund Spenser’s epic poem Faerie Queene, hyenas are deceitful, lustful beasts conjured by witches. Ernest Hemingway best summarizes the historical prejudices against the hyena in a passage from Green Hills of Africa, in which he describes gleefully killing the animals: “[T]he hyena, hermaphroditic self-eating devourer of the dead, trailer of calving cows, ham-stringer, potential biter-off of your face at night while you slept, sad yowler, camp-follower, stinking, fowl, with jaws that crack the bones that the lion leaves, belly dragging, loping away on the brown plain, looking back, mongrel dog-smart in the face...” (Ernest Hemingway, Green Hills of Africa, Simon and Schuster, 1996 [Scribner, 1935], 37-8).

In fact, hyenas can be prolific, fearsome hunters in the wild and display intense loyalty to the pack. Yet, recovering an idealized image of the proud hyena may be as illusory a proposition as finding in the animal a “friend.” Through their interactions with humans, the hyenas in Hugo’s photographs have become the debased scavengers of cultural imagination. Wholly dependent upon the itinerant group, they move from town to town in an existence that guarantees little food. The hyena’s nomadic hunting and scavenging may play a central role in the ecosystem of the Serengeti, but photographed on the outskirts of Abudja, their wandering symbolically conjures the human condition of homelessness and exile. The hyenas have clearly been displaced, perhaps cruelly, into a human social framework where they function purely as a spectacle of displacement. Still, Hugo’s work complicates appeals to animal rights. These photographs present the hyena’s captivity as a double-sided relationship in which the humans may be just as displaced as their non-human counterparts.

(courtesy of yossi milo)

In the title of the exhibition, “The Hyena and Other Men,” “hyena” functions as an adjective that modifies “men,” implying a human identity constituted in relation to the animal. It is an identity that has deep roots in West Africa. Keeping hyenas has been an esoteric tradition in Nigeria, handed down from fathers to sons for hundreds of years, possibly longer. Hyenas play a central role in folktales across the continent and are frequently associated with magic; one source of income for the hyena men is the sale of special herbs thought to provide strength and protection from wild beasts. On this level, the human-hyena relationship might be described as sacred in the sense of a removal or exclusion. An identity structured in relation to the hyena sets men apart from the mundane and situates them in a world of magic, theater, and animistic tradition.

The legibility of this specific mode of setting-apart, however, depends upon a social cohesion that may no longer have traction on the outskirts of a twenty-first-century megalopolis like Abuja. The dusty roads and anonymous urban landscapes in the background of Hugo’s photographs suggest that the hyena men are not the first itinerants to have passed through. In the absence of a stable cultural framework for interpreting the Gadawan Kura’s specific relationship to the hyena, the sacred can be read as banditry and criminality, forms of exclusion more common to urban environments, forms which newspaper captions can more easily explain.

When the hyenas enter a town, they cause a spectacle that Hugo describes as overwhelming. But the photographs offer little information about the audience for a hyena performance and even less about their broader status in Nigerian society. Most of the compositions isolate individual men and animals in an otherwise depopulated landscape of shantytowns and highway overpasses. These are spaces in flux: streets and concrete houses appear to be either under construction or already in ruins. The partial infrastructure suggests an equally incomplete consolidation of the codes and conventions of urban life. The men’s fashion is partial too: they wear ankle-length gowns of decorative patchwork that suggest traditions that we may never be able to fully understand, while their faded tank tops, acid-washed muscle shirts, and vinyl flip-flops clearly signify a globalized Third World. All signs point to a stalled or miscarried process of urbanization within which anything might go.

(courtesy of yossi milo)

Displayed in New York art galleries, the images of the hyena men refer to a form of exclusion defined by the fraught history of Western representations of Africa in which proximity to animals can denote a lapse of humanity. In some circumstances, humans gain currency through relationships with animals insofar as they speak to an authentic life founded upon a mastery of nature. Cowboys, for instance, continue to play a central role in constituting and affirming an American national identity based on the conquest of a frontier. However, outside such narratives of progress, these relationships often evoke the sub-human, the enfant sauvage, the barbarian.

Haunting the photographs of the Gadawan Kura are the permeable boundaries between the human and non-human that have circulated within discourses of anthropology and natural history. Compare Hugo’s portfolio, for instance, with a photograph of a group of men and their hyenas published in a 1914 issue of the anthropology journal Man. An off-axis horizon line denotes the immediacy of a snapshot. None of the subjects acknowledge the camera; the man holding the hyena is fully turned away. The photograph’s caption simply reads, “figure 3,” reminding us that it is an illustration to an extended textual exegesis of a rite that involves hyenas. The casual composition and textual framing of the image insist upon its truth value, marking the image as transparent evidence of a close human-animal relationship.

Understanding just how close that relationship was became a defining concern of much twentieth-century anthropology. The modern discipline, dedicated to the study of “man,” assumed a definitive and measurable split between the human and the animal, but because humans and animals share a basic biological existence, identifying the precise nature of that split has not always been easy. Philosopher Giorgio Agamben describes an “anthropological machine” that produces the human by isolating and excluding the inhuman, i.e. animal life, which exists within people. He writes: “It is possible to oppose man to other living things... only because something like an animal life has been separated within man, only because his distance and proximity to the animal have been measured and recognized first of all in the closest and most intimate place” (The Open: Man and Animal, trans. Kevin Attell, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004: 16). The presence of an animal existence within all humans has generated the constant need to re-articulate the human as a space beyond the animal, i.e. a space that constitutes the foundation of human rights. However, the ambiguity as to where the animal ends and the human begins also raises the possibility of those in power warping the category of the “human” in order to deny fundamental rights. Agamben refers to the split between human and animal as a zone of indistinction. On this unsteady ground, certain rights and values have been established, while, at the same time, the greatest crimes against those designated as less than human have been justified.

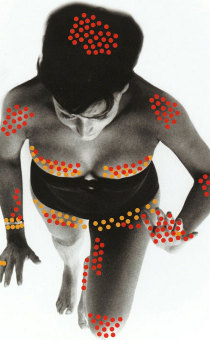

By drawing together humans and animals as the subjects of double-portraits rather than objects of anthropological study, Hugo’s photographs reveal both the distance and proximity between humans and animals that define this zone of indistinction. The photographs capture moments off-stage when the Gadawan Kura are no longer entertaining a crowd, but it is clear that at least the men are still performing in complicity with the camera. The portrait entitled Abdullahi Mohammed with Mainasara depicts Abdullahi Mohammed standing poised, staring at the camera while the hyena grasps his torso with its front legs. In Mallam Galadima Ahmadu with Jamis, Mallam Galadima addresses the camera with a calculated nonchalance as he exposes the hyena’s teeth.

(courtesy of yossi milo)

The men’s acknowledgement of the camera suggests a degree of agency in the production of the images, but it also underscores the fact that the hyenas are not performing and are not capable of doing so in the same sense. Although they share the space of the photograph and receive equal billing in the titles, a deep rift divides the two species of subject. To borrow terms from Michael Fried, the men take a theatrical stance, acknowledging the artifice of the portrait and the presence of the viewer. The hyenas, on the other hand, are completely absorbed, unaware of the camera and its functions. All of the photographs, even those that depict tender moments, such as when a young girl rests on the back of a hyena, are racked with a tension emerging from the split between absorption and theatricality and that between the animal and the human. This tension comes across most subtly, however, in the portraits of the “other men,” those who handle monkeys or snakes rather than hyenas. In Dayaba Usman with the Monkey Clear, a human and a monkey sit side by side on a narrow bench. They are dressed similarly, with the monkey in children’s clothing. A long thin chain tethers them together—a precaution that appears superfluous as Clear grasps Usman’s leg. With their heads tilted at almost exactly the same angle, both seem to address the camera. Yet while Usman stares directly at us, albeit with uncertainty, the monkey’s gaze is just off, vacant and distant. The monkey is equally the subject of the portrait, but nonetheless without subjectivity.

Although only the humans convey a glimmer of acknowledgment, they share with their non-human counterparts a basic struggle for survival on the margins of the city. While neither “elevating” the animals to human subjectivity, nor “reducing” humans to the level of the animal, Hugo’s photographs capture an existence held in common by two species. What might be disturbing about this bond is not just that it has been forged within a world of cruelty and dislocation, but that it seems inadequate to redress these conditions in terms of an anthropological machine that assigns rights according to a split between humans and animals. In his artist’s statement, Hugo describes how his thoughts about the images, and those of others, have been polarized along species-specific lines: “Europeans invariably only ask about the welfare of the animals but this question misses the point. Instead, perhaps, we could ask why these performers need to catch wild animals to make a living.” Perhaps, however, the real challenge posed by these images may not be determining whether humans or animals have it worse in twenty-first-century Nigeria. Instead, they demand an understanding of political and social marginalization that can accommodate relationships of interdependency between humans and animals, even one as improbable as that between hyenas and men.