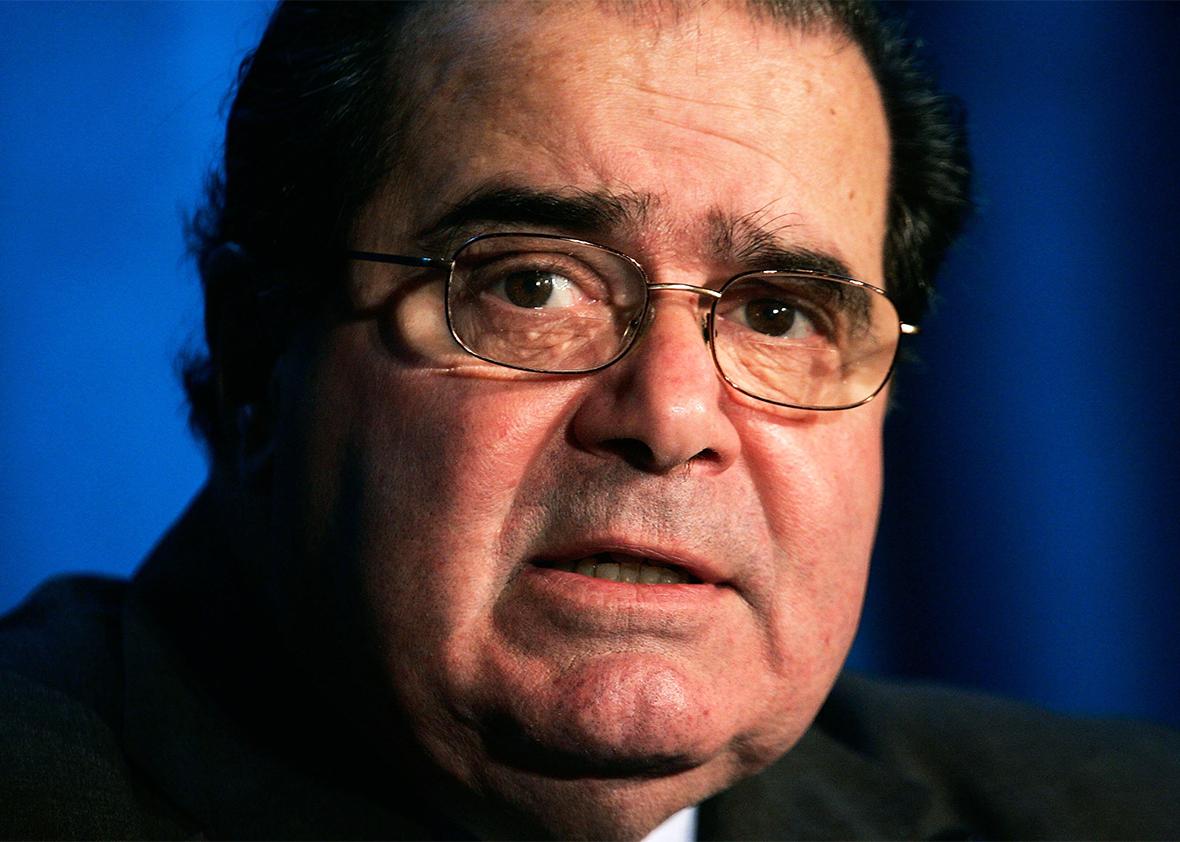

One of the things that makes legal scholars and legal geeks tick is the challenge of separating out what the law actually allows—or what it prohibits—from how we wish the world to look. This is especially true of constitutional law, since the point of a constitution is to place firmer limits on the whims of the people than ordinary laws create. This is one reason why those of us affected by, or following, LGBTQ equality in the courts regarded Justice Antonin Scalia as presenting a peculiarly inspiring challenge. As Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick noted, he said the worst things in the most intriguing ways. Like many legal minds—but particularly conservative ones—Scalia sometimes seemed to delight in pointing out the terrible things the law permitted people to do to one another, even if ethics, kindness, or pragmatism constrained them from actually doing them. That often raised the question of whether he actually found those things to be so terrible after all.

When it came to LGBTQ equality, Scalia’s rhetoric could be venomous—though the poison generally worked by implication. And so part of the challenge with Scalia was divining whether and how much he despised homosexuality by reading between the lines of his opinions—and then deciding if it even mattered if he was anti-gay. Did his views inevitably affect his judicial opinions? And did his stinging rhetoric have an impact beyond the court?

The Supreme Court has now issued four landmark rulings protecting gay rights across two decades—all written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, and all spurring bitter dissents from Scalia. In the first, Romer v. Evans, decided in 1996, Scalia defended a Colorado law that stripped gay people of anti-discrimination protections. He called the measure a “modest attempt by seemingly tolerant Coloradans to preserve traditional sexual mores against the efforts of a politically powerful minority”—the same year Congress voted overwhelmingly to define marriage as a club gays and lesbians could not join. Scalia not only called the law constitutionally “unimpeachable” and “an appropriate means” to a “legitimate end”; he took particular umbrage that the court would place the “prestige of this institution behind the proposition that opposition to homosexuality is as reprehensible as racial or religious bias.”

In slamming the court for imposing on the nation the view that “animosity” against gay people was “evil,” Scalia was, on the surface, simply saying that the justices, and the Constitution they were sworn to uphold, had no authority to make such a judgment. He said nothing about whether or not the judgment was correct, and that was precisely his point: He believed it wasn’t his or any justice’s place to do so. And since the Constitution remained silent on the matter, in his view, Colorado was perfectly free to target gay people, if that’s what its citizens wanted.

Of course, while Scalia declined to issue a moral judgment about homosexuality—or homophobia—in his text, it’s not hard to read between the lines. It is tough to imagine the expression of anger about the court putting its imprimatur on gay rights coming from someone who was not, personally, affronted by the prospect that his own anti-gay sentiment might now be considered “evil.” And elsewhere in his dissent, he spoke of homosexual conduct alongside murder, polygamy, and animal cruelty—all as legitimate targets of moral disapproval.

Still, if animosity toward homosexuality (not to be confused, he would point out, with animosity toward gay people) was perfectly acceptable to Scalia, that doesn’t, in itself, prove that he let such views cloud his judgment as a jurist. However, his dissent in Lawrence v. Texas was even more strident—and revealing. The 2003 case overturned sodomy bans, reversing the court’s decision to uphold such laws in Bowers v. Hardwick just 17 years earlier—mere months before Scalia joined the court.

Again, Scalia viewed moral disapproval as a wholly legitimate rationale to target gay people in law, and he railed against the court’s imposition of judgments he believed should be left to the “democratic process” (which has come, somehow, to exclude the court’s role entirely). The law has long relied, he wrote, “on the ancient proposition that a governing majority’s belief that certain sexual behavior is ‘immoral and unacceptable’ constitutes a rational basis for regulation.” Yet now the court has “taken sides in the culture war” and signed onto the “so-called homosexual agenda,” which includes not only eliminating moral disapproval as a basis for law, but—gasp—“eliminating the moral opprobrium that has traditionally attached to homosexual conduct.”

The fact is, he wrote bluntly, “Many Americans do not want persons who openly engage in homosexual conduct as partners in their business, as scoutmasters for their children, as teachers in their children’s schools, or as boarders in their home.” Not only do they not want to associate with gay people, he went on, they view avoiding gay people as a way of “protecting themselves and their families from a lifestyle that they believe to be immoral and destructive.”

Although such a statement was rendered as an empirical assertion about what “many Americans” felt, rather than an expression of Scalia’s own wish to exclude and avoid gay people, it is, once again, exceedingly difficult to imagine someone offering this description—without qualification—if he did not share its sentiment.

Could he simply have been interpreting the Constitution and not expressing his own animosity toward homosexuality? As a champion of originalism, this is what Scalia wanted us to believe—that he was truly neutral. And yet the job description of being a Supreme Court justice requires imposing more than just legal judgments. In order to do their jobs, justices must also sometimes determine what is “rational” or “irrational,” “legitimate” or illegitimate”—highly subjective terms (as are terms like “immoral and unacceptable”). In the Lawrence case, the question as Scalia himself framed it was whether the freedoms being denied to gay people were “rationally related to a legitimate state interest.” Scalia, agreeing with the Bowers decision, answered that they were, that what’s known as the “rational basis test” was satisfied by the state’s interest in the “enforcement of traditional notions of sexual morality.”

Of course, Scalia could not simply declare, out of whole cloth, that enforcing moral views was a “legitimate” state interest; he had to make a case for it. And here, while he tried to embed his argument in precedent and history, he revealed his biggest intellectual blind spots. The law, he argued, is routinely based on moral sentiment. He meant the statement to apply broadly to all morals, but his fixation was sexual morality. In addition to sodomy bans, “state laws against bigamy, same-sex marriage, adult incest, prostitution, masturbation, adultery, fornication, bestiality, and obscenity,” he fretted, can only be justified if laws based on “moral choices” are permissible. “Every single one of these laws is called into question by today’s decision,” he wrote of the Lawrence majority.

The trouble was that, as Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote in a concurring opinion in Lawrence, the court had “never held that moral disapproval, without any other asserted state interest, is a sufficient rationale” for trumping a group’s constitutional freedoms. That “other asserted state interest” is key to justifying challenged laws, especially when they conflict with individual rights. That Scalia believed that so many laws could be sustained only by relying on the moral sentiments of the populace reveals a stunningly constricted view of both morality and the law.

Moral judgment is not reducible to mere taste or preference; it is a considered opinion about what actions are harmful or helpful to others. Hence lumping homosexuality in with bigamy, incest, prostitution, and adultery is imprecise at best, since they arguably cause harm, while homosexuality—along with masturbation, fornication, and same-sex marriage—do not. Scalia’s constrained understanding of morality seemed blindly inherited not only from his Catholic upbringing but from the hostile takeover of the very concept of morality by the Christian right, which beginning in the 1970s, turned moral judgment into little more than sexual restraint.

Scalia’s blind spot on morality was his own moral—and judicial—weakness, spurring alarmist “slippery slope” thinking and increasingly bitter resignation to modernity. In some cases, of course, he was right. The majority’s Lawrence opinion, he assured us, “leaves on pretty shaky grounds state laws limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples.” Ten years later, Scalia found himself angrily dissenting in U.S. v. Windsor. By then he had almost moved on from his fixation on morality as the basis of law. He still insisted that, despite Romer and Lawrence, it was perfectly constitutional for the government “to enforce traditional moral and sexual norms.” Yet “even setting aside traditional moral disapproval” of homosexuality, he wrote, there were “many perfectly valid—indeed, downright boring—justifying rationales” for the Defense of Marriage Act beyond anti-gay animosity, yet he made little effort to explain what those could be.

By the time of his 2015 dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges, which ended same-sex marriage bans nationwide, he took an almost ho-hum tone that was oddly personal, claiming that “it is not of special importance to me what the law says about marriage.” But then, summoning back his righteous anger, he wrote that “it is of overwhelming importance, however, who it is that rules me.” He then launched into yet another tirade against the court issuing judgments that he believed thwarted the democratic process, which meant letting the people decide if their animus should stop gay people from sharing equal rights.

Yet if Scalia was right that same-sex marriage was next, his continued commitment to allowing moral disapproval to make homosexuality, fornication—even masturbation—illegal ended up making him seem not only narrow-minded, but also fixated on a constricted view of sexual morality and blinded by his own anti-gay bias. Outside of his written opinions, Scalia gave a few hints to what he believed, at least consciously. He conceded that his Catholic beliefs viewed homosexuality as “wrong,” while he also insisted he was “not a hater of homosexuals” as people—the all too-familiar “hate the sin, love the sinner.” A devout Catholic, he told a biographer that he long ago learned not to “separate your religious life from your intellectual life,” essentially acknowledging that his anti-gay Christian worldview infused his thinking and his work. By his own account, he had no openly gay friends and seemed never to have absorbed what most of the rest of America has come to understand: that homosexuality is a profound, enduring, unchosen and harmless identity, not a mere sexual proclivity or fetish that could or should be snuffed out.

So if Scalia was ultimately unable to view LGBTQ people as true equals, does it matter? Does it make his anti-gay legacy any more influential or important than that of any other public figure with similar views? I’ve posited that his personal views affected his judgment as a jurist, given the reality that, in determining what is rational or legitimate, a justice must draw on all that he or she knows and believes. It is also true that, even though his anti-gay opinions were usually in the minority, those opinions were often cited by lower courts. And beyond that, their particular vehemence had an impact. “His intemperate tone has seemed intended to inspire anger and alarm among those working for reactionary causes,” Lambda Legal’s Jenny Pizer recently observed.

Justice Scalia said harmful, hurtful things about LGBTQ people, things that reflect ugly, stubborn, unevolved beliefs. But there is another side to this. In his brilliance and boldness, he asked sharp, hard questions that made the rest of us grapple with the real, strong justifications for advancing LGBTQ equality. Even when revealing his blind spots—on the nature and role of morality in the law—he helped advance the nation’s understanding of the relationship between homosexuality and morality by focusing so relentlessly on the subject in his opinions. It may not be the legacy he wanted to leave, but it was something the country needed to go through, and in that sense, we’ll be better off for it in the end.

See more of Slate’s coverage of Antonin Scalia.