This EU study of national programmes for mass surveillance of personal data in EU member states - the UK, Sweden, France, Germany and the Netherlands - and their compatiblity with EU law, was published in October 2013. This is the executive summary and introduction.

Surveillance of population groups is not a new phenomenon in liberal regimes and the series of scandals surrounding the surveillance programmes of the National Security Agency (NSA) in the US and the UK’s Government Communications Headquarters (GHCQ) only reminds us of the recurrence of transgressions and illegal practices carried out by intelligence services. However, the scale of surveillance revealed by Edward Snowden should not be simply understood as a routine practice of intelligence services. Several aspects emerged from this series of revelations that directly affect EU citizens’ rights and EU institutions’ credibility in safeguarding those rights.

First, these revelations uncover a reconfiguration of surveillance that enables access to a much larger scale of data than telecommunications surveillance of the past. Progress in technologies allows a much larger scope for surveillance, and platforms for data extraction have multiplied.

Second, the distinction between targeted surveillance for criminal investigation purposes, which can be legitimate if framed according to the rule of law, and large-scale surveillance with unclear objectives is increasingly blurred. It is the purpose and the scale of surveillance that are precisely at the core of what differentiates democratic regimes from police states.

Third, the intelligence services have not yet provided acceptable answers to the recent accusations directed at them. This raises the issue of accountability of intelligence services and their private-sector partners and reinforces the need for a strengthened oversight.

In light of these elements, the briefing paper starts by suggesting that an analysis of European surveillance programmes cannot be reduced to the question of a balance between data protection versus national security, but has to be framed in terms of collective freedoms and democracy. Our report underlines the fact that it is the scale of surveillance that lies at the heart of the current controversy. We also outline the main characteristics of large-scale telecommunications surveillance activities/capacities of five EU member states: the UK, Sweden, France, Germany and the Netherlands. This analysis reveals in particular the following:

- Practices of so-called ‘upstreaming’ (tapping directly into the communications infrastructure as a means to intercept data) characterise the surveillance programmes of all the selected EU member states, with the exception of the Netherlands for which there is, to date, no concrete evidence of engagement in large-scale surveillance.

- The capacities of Sweden, France and Germany (in terms of budget and human resources) are low compared to the magnitude of the operations launched by GCHQ and the NSA and cannot be considered on the same scale.

- There is a multiplicity of intelligence/security actors involved in processing and exploiting data, including several, overlapping transnational intelligence networks dominated by the US.

- Legal regulation of communications surveillance differs across the member states examined, but in general legal frameworks are characterised by ambiguity or loopholes as regards large-scale communications surveillance, while national oversight bodies lack the capacity to effectively monitor the lawfulness of intelligence services’ large scale interception of data.

This empirical analysis furthermore underlines the two key issues remaining unclear given the lack of information and the secretive attitude of the services involved in these surveillance programmes: what/who are the ultimate targets of this surveillance exercise, and how are data collected, processed, filtered and analysed?

The paper then presents modalities of action at the disposal of EU institutions to counter unlawful large-scale surveillance (section 3). This section underlines that even if intelligence activities are said to remain within the scope of member states’ exclusive competences in the EU legal system, this does not necessarily means that member states’ surveillance programmes are entirely outside the remits of the EU’s intervention.

Both the European Convention on Human Rights and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights could play a significant role here, especially given the fact that, from a legal point of view, EU surveillance programmes are incompatible with minimum democratic rule-of-law standards and compromise the security and fundamental human rights of citizens and residents in the EU. The forthcoming revision of Europol’s legal mandate appears to be a timely occasion to address the issue of EU competence and liability in sharing and exploiting data generated by national large-scale surveillance operations and to ensure greater accountability and oversight of this agency’s actions.

The briefing paper concludes that a lack of action at the EU level would profoundly undermine the trust and confidence that EU citizens have in the European institutions. A set of recommendations is outlined, suggesting potential steps to be taken by the EU and directed in particular at the European Parliament.

Introduction: scope of the problem

Following the revelations of Edward Snowden, a former contractor working for the US National Security Agency (NSA), published in The Guardian and the Washington Post on 6 June 2013, concerning the activities of the NSA and the European services working with them, it appears that:

- First, the US authorities are accessing and processing personal data of EU citizens on a large scale via, among others, the NSA’s warrantless wiretapping of cable- bound internet traffic (UPSTREAM) [1] and direct access to the personal data stored in the servers of US-based private companies such as Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Apple, Facebook and Skype - through the NSA’s programme Planning Tool for Resource Integration, Synchronisation, and Management (PRISM). This allows the US authorities to access both stored communications as well as to perform real-time collection on targeted users, through cross-database search programmes such as X-KEYSCORE. UPSTREAM, PRISM and X-KEYSCORE are only three of the most publicised programmes and represent the tip of the iceberg of the NSA’s surveillance. [2]

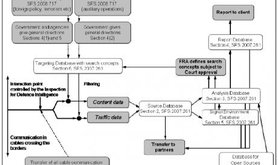

- Second, the UK intelligence agency, the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), has cooperated with the NSA and has initiated actions of interception under a programme code-named TEMPORA. Further reports have emerged implicating a handful of other EU member states (namely Sweden, France and Germany) that may be running or developing their own large-scale internet interception programmes (potentially the Netherlands), and collaborating with the NSA in the exchange of data.

- Third, EU institutions and EU member state embassies and representations have been subjected to US-UK surveillance and spying activities. The European Parliament’s Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) recently received testimony on how the UK GCHQ infiltrated the systems of Belgacom in what was codenamed ‘Operation Socialist’ to gain access to the data of the European institutions. [3] A letter from Sir Jon Cunliffe, the UK Ambassador to the EU, stated that the GCHQ chief would not appear (at the hearing) since “the activities of intelligence services are... the sole responsibility of EU member states”.

-

The questions opened by these NSA activities and the European services working with them directly affect the EU institutions and necessitate a specific inquiry by the European Parliament, given that these matters clearly affect EU affairs and interact with EU competence.

Beyond the specific case of the attacks against the EU institutions, these secret operations impact, first, the daily life of all the individuals living inside the European Union (citizens and permanent residents) when they use internet services (such as email, web browsing, cloud computing, social networks or Skype communications – via personal computers or mobile devices), by transforming them into potential suspects.

Second, these operations may also influence the fairness of the competition between European companies and US companies, as they have been carried out in secret and imply economic intelligence; third, some governments of the EU were kept unaware of these activities while their citizens were subject to these operations. An inquiry is therefore central and needs to be supported by further in-depth studies, in particular in the context of EU developments in the area of rule of law.

In addition to the fact that these operations have been kept secret from the public, from companies and branches of governments affected by them (with the possible exception of the intelligence communities of some European countries), the second salient characteristic of these operations is their ‘large-scale’ dimension, which changes their very nature, as they go largely beyond what was previously called ‘targeted surveillance’ or a non-centralised and heterogeneous assemblage of forms of surveillance. [4]

These operations now seem to plug in intelligence capacities on these different forms of surveillance via different platforms and may lead to data-mining and mass surveillance. The different interpretations of what constitutes large-scale surveillance are discussed in detail below.

A large part of the world’s electronic communications transiting through cables or satellites, including increasingly information stored or processed within cloud computing services (such as Google Drive or Dropbox for consumers; Salesforce, Amazon, Microsoft or Oracle for businesses) i.e. petabytes of data and metadata, may become the object of interception via technologies put in place by a transnational network of intelligence agencies specialised in data collection and led by the NSA. The NSA carries out surveillance through various programmes and strategic partnerships. [5]

While the largest percentage of the internet traffic is believed to be collected directly at the root of the communications infrastructure, by tapping into the backbone of the telecommunications networks distributed around the world, the recent exposure of the PRISM programme has revealed that the remaining traffic is tapped through secret data collection and data extraction of nine US-based companies: Microsoft, Google, Yahoo, Facebook, Paltalk, Youtube, Skype, AOL and Apple. The surveillance programmes therefore imply not only governments and a network of intelligence services, but they work through the ‘forced’ participation of internet providers as a hybrid system, as part of a Public-Private-Partnership (PPP) whose consent is limited.

On the basis of the provisions of the US Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), the NSA, with an annual ‘certification’ of the FISA court, can target any non-US citizen or non-US legal resident located outside the territory of the US for surveillance. These data, once intercepted, are filtered and the suspicious ones are retained for further purposes by the NSA and GCHQ. The stored data can then be aggregated with other data, and be searched via specifically-designed programmes such as X-KEYSCORE.

Furthermore, internet access providers in the US (but also in Europe) are under the obligation to keep their data for a certain period, in order to give law enforcement agencies the possibility to connect an IP address with a specific person under investigation. The legal obligations concerning access to data and privacy law derogations vary for the internet providers and the intelligence services, depending on the nationality of the persons under suspicion.

This has very important consequences for the European citizen using cloud computing or any internet service that transits through the US cable communications systems (possibly all internet traffic) on various levels:

- At present, the debate in the US on PRISM has centred on the right of American citizens to be protected from illegitimate purposes of data collection by NSA and other US intelligence agencies, with a focus on the US Patriot Act and FISA reforms. But the debate has been confined to US citizens in the context of US institutions and Constitutional frameworks. The implications for EU citizens need to be addressed too.

- As explained in a previous study by Caspar Bowden, it is quite clear that European citizens whose data are processed by US intelligence services are not protected in the same way as US persons under the US Constitution in terms of guarantees concerning their privacy. Consequently the data of European data subjects are ‘transferred’ or ‘extracted’ without their authorisation and knowledge, and a legal framework offering legal remedies does not currently exist.

Under European law, the individual owns his/her own data. This principle is central and protected by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and the Treaty on the European Union. This aspect raises important legal issues that will be tackled in section 3 of our study: Can we consider unauthorised access to data as ‘theft’ (of correspondence)? Currently, channels permitting lawful search exist, such as the EU-US Mutual Legal Assistance Agreement (MLAA), which covers criminal investigations and counter terrorism activities. However, in light of recent revelations, have the US services and their European member state partners followed the rules of this agreement?

Moreover, and contrary to the US legislation, the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights requires data protection for everyone, not just EU citizens. The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) also guarantees the right to privacy for everyone not just nationals of contracting parties. Thus the overall framework of the right to privacy and data protection in the EU cannot be limited to EU citizens alone. However, protection arising from national constitutions could be also limited.

To solve this profound inequality of treatment, it would require either a change of US laws offering the same privacy rights to any data subject intercepted by their systems, regardless of their nationality, or an international treaty specifying a digital bill of rights concerning all data subjects, whatever their nationality.

The structure of the study

The study starts by shedding light on the Snowden revelations and highlights to what extent we are witnessing a reconfiguration of surveillance that enables access to a much larger scale of data than telecommunication surveillance of the past. ‘Large-scale’ surveillance is at the heart of both a scientific controversy about what the different technologies of interception of digital messages can do when they are organised into platforms and planning tools in terms of the integration of data, and a political and ethical controversy about the use of these technologies by the intelligence services. The two controversies are often interwoven by the different actors in order to argue over the legitimacy of such practices.

These preliminary remarks are critical for the second part of the study that deals with a comparative approach to European programmes of surveillance. Since the publication of the first revelations on the US PRISM programme, disclosures and allegations relating to large-scale surveillance activities by EU member states have emerged as a result of both the Snowden leaks and wider investigative journalism.

Section 2 draws on a country-by country overview of large-scale telecommunications surveillance activities/capacities of five EU member states: the UK, Sweden, France, Germany and the Netherlands. The section draws a set of observations concerning the technical features, modalities and targets pursued by the intelligence services of these EU member states in harvesting large-scale data, and examines the national and international actors involved in this process and the cooperation between them. It highlights the commonalities, divergences and cross-cutting features that emerge from the available evidence and highlights gaps in current knowledge requiring further investigation.

These empirical examples are followed by an investigation of modalities of actions at the disposal of EU institutions concerning large-scale surveillance (section 3). This section tackles the EU competences concerning NSA surveillance programmes and general oversight over EU member state programmes of surveillance. It assesses the relationship between surveillance programmes and EU competence, employing three legal modalities of action to critically examine EU surveillance programmes from an EU law viewpoint.

The study concludes with a set of recommendations addressed to the European Parliament with the aim of contributing to the overall conclusions and the next steps to be drawn from the LIBE Committee’s inquiry.

Methodological note

The exercise of piecing together the extent of large-scale surveillance programmes currently conducted by selected EU member states is hampered by a lack of official information and restricted access to primary source material. The empirical evidence gathered for the purpose of this study and presented in Annex 1 therefore relies on three broad forms of evidence:

- The reports and testimonies of investigative journalists. Much of the publicly available evidence covering EU member states’ engagement in mass surveillance-like activities stems from revelations of investigative journalists and their contacts with whistleblowers – current or former operatives of intelligence agencies. Press reports are in some cases very concrete in their sources (e.g. quoting from specific internal documents), while others are more ambiguous. Where possible we provide as much information concerning the journalistic sources used in this study; however, a cautious approach must be taken to material that researchers have not viewed first hand.

- The consultation and input of experts via semi-structured interviews and questionnaires. Experts consulted for this study include leading academic specialists whose research focuses on the surveillance activities of intelligence agencies in their respective member states and its compatibility with national and European legal regimes.

- Official documents and statements. Where possible, the study makes reference to official reports or statements by intelligence officials and government representatives which corroborate/counter allegations concerning large-scale surveillance by intelligence services of EU member states.

[1] The UPSTREAM programme was revealed as early as 2006, when it was discovered that the NSA was tapping cable-bound internet traffic in the very building of the SBC Communications in San Francisco.

[2] Other high-profile NSA electronic surveillance programmes include: Boundless Informant, BULLRUN, Fairview, Main Core, NSA Call Database and STELLARWIND.

[3] In a post published on 20 September 2013, Der Spiegel journalists who had access to Snowden documents stated: “According to the slides in the GCHQ presentation, the attack was directed at several Belgacom employees and involved the planting of a highly developed attack technology referred to as a ‘Quantum Insert’ (QI). It appears to be a method with which the person being targeted, without their knowledge, is redirected to websites that then plant malware on their computers that can then manipulate them.”

[4| K. Haggerty and R. Ericson, (2000), “The Surveillant Assemblage”, British Journal of Sociology, 51(4): pp. 605-622. See also D. Bigo (2006), “Intelligence Services, Police and Democratic Control: The European and Transatlantic Collaboration”, in D. Bigo and A. Tsoukala (eds), Controlling Security, Paris: L’harmattan.

[5] The NSA functions in particular as the centre of the network codenamed ‘Five Eyes’ (US, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand).

Read more from our 'Joining the dots on state surveillance' series here.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.