For 12 years, visitors wanting to see Spain's prized prehistoric Altamira cave paintings have had to settle for a replica in a museum a few hundred feet away.

But from Thursday, small groups of visitors will again be allowed in the cave, which has been described as the Sistine Chapel of paleolithic art, as part of an experiment to determine whether the paintings can support the presence of sightseers.

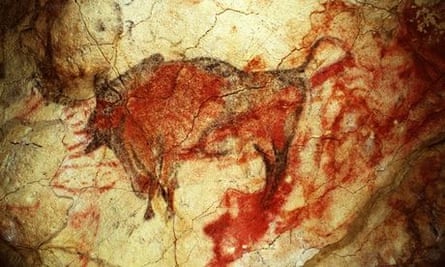

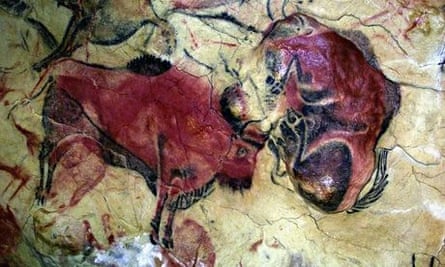

The vast cavern complex, in the Cantabria region of northern Spain, was made a World Heritage Site by Unesco in 1985. It is covered in paintings dated to between 14,000 and 20,000 years ago of animals including European bison and bulls.

From now until August, on a randomly selected day of the week, visitors to the replica cave in the Museo de Altamira will be invited to enter a draw; five will be chosen to take a guided tour including 37 minutes inside the cave. Visitors will have to put on special suits, masks and shoes before entering the site.

Up to 192 lucky winners are expected to visit the cave in total. While they admire the red and black paintings on the limestone walls, researchers will measure their impact on the cave's temperature, humidity, microbiological contamination and CO2 levels.

The results will be used to determine whether or not the cave can be reopened to the public, a controversial decision that has pitted the local tourist economy against government scientists.

The site has been closed several times, starting in 1977 after scientists warned that body heat and CO2 levels from the 3,000 daily visitors were deteriorating the paintings. When the cave was re-opened again, to a limited amount of visitors, the waiting list swelled, leaving people waiting up to three years to get a glimpse of the prehistoric masterpieces.

The cave was again closed to the public in 2002 after scientists blamed body heat, light and moisture for the appearance of green mould on some of the paintings.

Since then, the regional government of Cantabria has been lobbying for the site to be reopened. "Altamira is a valuable asset that we cannot afford to do without," Miguel Ángel Revilla, former head of the regional government of Cantabria, told El País. "Every famous person who comes here wants to visit it. I've had to tell [former presidents] Jacques Chirac of France and Felipe Calderón of Mexico that they couldn't."

His position runs counter to that of scientists at the government's main research body. A 2010 report, by the Spanish National Research Council warned of the dangers of letting visitors into the complex.

"The people who go in the cave have the bad habit of moving, breathing and perspiring," was one of the conclusions. The report made it very clear that the cave shouldn't be open to visitors, lead researcher Sergio Sánchez Moral recently told Público.es, warning: "The consequences of doing so are immeasurable."

José Antonio Lasheras, director of the Museo de Altamira, defended the decision. The tours, he said, were part of a carefully calculated equation to find a balance between conservation efforts and making the country's heritage as accessible as possible.

While the museum's replica of the cave may give people a sense of the place, he said, "the emotion: we can't give that. The emotion can come only from being inside the cave of Altamira."

Opening the cave to visitors, said Lasheras, could be likened to hanging a painting by Velázquez in the Museo Nacional del Prado, or one by Turner in Tate Britain.

"We also take a risk when we hang our best paintings in museums," he said. "We don't put these paintings in Trafalgar Square, where more people would see them; nor do we keep them in a closed-off room, where nobody would see them. It's a controlled risk."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion