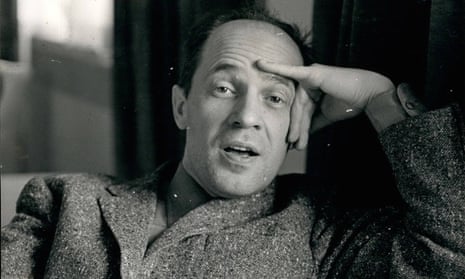

“Schoenberg is dead”; “Blow up the opera houses”; “Authenticity is a nightmare”; Henze? “rubbish”. Verdi? “dum de dum, nothing more”. Shostakovich? “the second or even third pressing of Mahler”: all the typically outspoken views of the great musical iconoclast of the late 20th century, composer, conductor, writer, theorist and thinker Pierre Boulez, who died last week after a long illness at the age of 90.

This strident figure, who emerged from the postwar years as a turbulently individual pupil of Messiaen, was ready to rubbish most of history in the search for the one new path of the music of the future. He cast a huge shadow over the decades that followed, and as both creator and interpreter was surely the single most influential person in the musical life of our time. Forget Karajan; this was the man who moved our culture decisively forward and changed our taste for ever.

Yet that rebarbative Pierre Boulez was, oddly, not quite the same Boulez who those of us who worked with him across the years recognised. For us he was an effortlessly polite, gentle, very funny and totally absorbing maker of music: a supreme professional who led orchestras with a minimum of fuss and a maximum of effectiveness. His requests were always reasonable and perfectly measured; his relationships with his players warm and based on total mutual respect. He never craved adulation, but after a concert he always enjoyed a good meal, preferably accompanied by a piece of new gossip and anecdotes of musical disasters.

For more than 40 years, from 1965 to 2008, he appeared at the BBC Proms. Proms controller (and former Observer music critic) William Glock encouraged him to come to this country in an extraordinary act of faith, since Boulez was then a composer of the avant garde who conducted his own music (since few then understood it) but not much else. He had been the musical director of Jean-Louis Barrault’s theatre company in Paris, and the BBC Third Programme had very grudgingly broadcast a chamber music concert in the 1950s. But, bizarrely, his first date with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, in 1964, was in Worthing, where they had to accompany a young Vladimir Ashkenazy in a Chopin piano concerto. “I felt like a waiter who keeps dropping the plates,” Boulez said.

To the Proms he then brought his own core repertory – Webern, Berg, Stravinsky, Debussy – and the clarity and transparency of his performances made an immediate impact. Boulez triumphed as a programmer and conductor of genius because he made 20th-century music, so baffling to many, make sense for audiences. In one 1967 Prom he conducted fragments from Berg’s Wozzeck, Stockhausen’s Gruppen for three orchestras and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. The hall was overflowing: how pleased Boulez would have been, one suspects, in spite of the many rivalries with his contemporary, to hear that Stockhausen was at last Radio 3’s composer of the week in the network’s current New Year New Music season.

The Boulez revolution in this country rolled forward: the events of 1968 in Paris halted his ambitious plans to reform musical and operatic life there, and Boulez was free to accept a rapid offer from Glock for him to become chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra. The Observer’s then music critic, Peter Heyworth, was Boulez’s closest supporter and advocate in the press. Boulez said to him: “I want to create conditions in which the music of our own time is once again an integral part of concert life… There are plenty of conductors as good as me and some who are much better in parts of repertory. But it’s the ideas I want to put into practice that count.”

In that thrilling period in the 1970s, Boulez’s ideas were fertile rain on the parched ground of London concert life: themed seasons at the Royal Festival Hall, built around forms and composers: Haydn and Stravinsky in his opening season. He used varying venues: the famous, informal Roundhouse concerts in Camden where Boulez gave premieres and led rambling audience conversations about the new pieces; and at St John’s Smith Square, where Glock’s beloved Haydn sounded so well. For those of us new to London at the time, these events were a revelation, and perhaps against the odds they drew large crowds.

What gave Boulez’s interpretations their wholly distinctive sound? Accuracy, fluidity, rhythmic sharpness and an acute sensitivity to different orchestral sonorities – all of which put him strangely alongside the sound of the historical performance movement whose principles he so despised. He did not use a baton, and his gestures were undemonstrative to a fault. He liked to say “too much outer energy uses up inner energy”, and the concentration of his conducting was amazing, since he could hear and observe every note in the orchestra. His were surely the finest ears in the musical world.

Yes, he mellowed. He never found the single path of new music, and accepted diversity. When I got to know him better his views were much less outspoken but still firm. He would never conduct Shostakovich (let alone Sibelius), though his sympathies expanded to include Szymanowski and then Janácek. An Indian summer of superb concerts with the LSO at the Barbican and around the world raised orchestral performance to new heights. A large collection of his early Columbia recordings has some stunning if low-fi performances showing his range from Handel (!) and Beethoven onwards; later recordings with the world’s great orchestras for Deutsche Grammophon gave us a superb hi-fi legacy.

And what of his own path-breaking music? That is another paradox: that this supposedly severe serialist gave us some of the most gorgeously voluptuous, colouristically French sounds of our time: dazzlingly virtuosic in Sur incises, innovatively electronic in Répons, sensually languorous in Le Visage nuptial, and massively complex yet inviting in Pli selon pli. Through his own radical music and his profound understanding of the music of others, he transformed our experience; we can only be deeply grateful for his influence, as our musical life looks for the next revolution.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion