The ban on sending books to prisoners has been causing a big stir among publishers, authors and the public. While the condemnations of the changes introduced by justice secretary Chris Grayling continue to pour in, we turned to our readers to ask what books they would give to someone in prison, and we had some very touching and interesting responses from people talking from direct experience. We asked them to tell us more about literature and its relationship to incarceration, as well as the troubles they went to to get access to books during their time inside. Here are some of their stories:

"The act of reading for eight - ten hours a day was one of absolute bliss"

Aaron Persichetti, 29

On the experience of incarceration:

I'm an American, Pittsburgh born. I'm rather rapidly approaching my 30th year. I was incarcerated in the Harris County jail (the largest jail in the city of Houston) for six weeks as a result of drink-driving (actually a serious crime that I do in fact regret) and possession of cannabis (not so serious and I've yet to feel a pang of guilt). We were housed in a concrete dormitory, between 30-35 guys per dorm, and we were segregated by our age (I was 19 at the time and thus was housed with 17-21 year olds). I did not see the sun for 40 some odd days, as we were not allowed outside.

On books read in prison:

As far as books were concerned, there was a heap of awful dime-store paperbacks, mostly genre fiction of the worst kind, i.e. very, very poor science fiction (no Asimov or Gibson), dystopian dreck (no Atwood or Mitchell), and dated political thrillers (not a fan anyway). When I think back, it occurs to me that the vast majority of the books on offer dated from the late 70s to early 80s (no classics).

In the end, I found a copy of The Hunt for Red October and I lost count of the number of times I read that book, probably five or six times (ironic that I don't fancy political fiction and yet that was what I read the most). Even though I wasn't that keen about the books offered, I ate them up as if they were caviar.

Not to take anything away from the late Mr. Clancy, but the book itself didn't do much for me. The act of reading for 8-10 hours a day however was one of absolute bliss; I only wish I had had all seven volumes of Proust. A downside of being in jail, as opposed to prison, is that people are not allowed to receive packages, hence no one could send me anything to read.

On literature, hope and change:

The literature I was reading didn't really change me, but the act of reading taught me how to cope with the time. Time is a river, and in jail/prison it moves at the rate of molasses (the metaphor is not mine). And it also taught me how much I love books, even the bad ones. As perverse as this sounds, I would do the time again if only I could select what books were available.

Literature serves a person well in prison, though it may take time to develop one's reading ability (by that I simply mean that reading for long periods at a time requires practice). I would emphasise that literature (reading in general) requires patience, and a patient person can overcome just about anything, even prison. Just ask Edmond Dantès.

"I still have that battered copy of The Count of Monte Cristo with my prison number written"

Anonymous, 26

On the experience of incarceration:

I was in Fleury Merogis, outside Paris for six months in 2008. It's the prison featured in the recent French film A Prophet. It was a little tough because I didn't speak a lot of French and there was only a handful of English speakers. However, I got a job in a factory sticking the free extras onto magazines. You know: perfume and shampoo samples, little hair clips, toys and colouring pencils on kids' publications. Working was good because it got you out of the cell, kept your mind busy, gave you a bit of pocket money and there was always a bit of banter on the factory floor.

Us workers lived on a separate wing of the prison and at the end of the day we got to walk in the yard for an hour, and the atmosphere in the workers' yard tended to be a little more subdued and civilised than in the yards of the wings where the inmates chose not to work. There were still gangs and fights of course, but people were generally more respectful to one another.

On the books read in prison:

I wasn't allowed to receive anything from outside and I didn't have access to the library. I was on a waiting list, although I have no idea how long that list was or how many people were allowed membership at one time. I knew a Bulgarian guy who had access to the library though, and he lent me War of the Worlds when he was finished with it. I quite enjoyed that, although it's not really the sort of thing I'd usually read. I also read The Leopard by Giuseppe di Lampedusa, which I had had on me when I was arrested but hadn't started and had been allowed to keep.

The other books I remember reading were translations of The Count of Monte Cristo and Papillon. Again, neither of these books are things I feel I would have been usually drawn to, but I enjoyed them both immensely. Funnily enough they're both French books involving prison breaks, and although written almost a century apart, they're both out and out adventures full of hope and redemption, which is lovely to read about when you're in prison.

I borrowed those books from the only other British guy on my wing, a middle-aged guy from the North West of England, although they came to me indirectly from an old Dutch gangster who'd been borrowing them first. They'd been sent in by the English guy's girlfriend and were well worn by the time they got to me. Their spines were cracked in several places and their covers were soft and curled, but that added to their charm. I felt privileged that it was my turn to accompany Papillon and Edmond Dantès on their long, exciting quests for freedom.

On literature, hope and change:

I bought a cheap radio with the first pay I got from my job in the factory and I was allowed to rent a small TV for my room when I started earning enough each week. Although I couldn't understand much French I enjoyed watching the odd film and – like the vast majority of us in there – I couldn't wait for those Tuesday and Wednesday nights when a European football match would be on. Almost every cell would have the game on the TV or radio and when goals went in the whole prison would erupt and shake with the noise of shouting and chanting, cell doors being banged and some inmates would throw burning balls of paper through the bars of their windows which, if enough people did it, lit up the sky like some kind of strange slow motion firework display.

But on a regular evening reading was the thing. Ultimately, nobody wanted to be there and for me a good book was simply the best escapism. But I've always felt that good literature makes real life more interesting and beautiful too, and it was a time when I needed that more than ever.

I still have that battered copy of The Count of Monte Cristo with my friend's name and prison number written on the inside the cover. I got released suddenly and unexpectedly and didn't get a chance to give it back, or pass it onto whoever was the next in line.

I feel sad and outraged to think that British prisoners might not get the chance to read a good book anymore. It seems unnecessarily cruel and inhumane.

"Reading 1984 was a big mistake"

William Tea, 49

On the experience of incarceration:

I was convicted of conspiracy to commit armed robbery and was sentenced to three years' imprisonment when I was 24 years old. I spent a total of fourteen and a half months in prison in the UK. I spent time in five high-security and one open prison. Since my release I have lived and worked in a large number of countries. Broadly speaking, I have been involved in "prison welfare" work in the UK, Germany and Australia. I have sent many, many different kinds of books and "publications" to prisoners with whom I have corresponded over the years.

On the books read in prison:

My least favourite was 1984. I read it in the remand wing of Wormwood Scrubs prison and that was a BIG mistake. The literary equivalent of music to cut your wrists to. In Wandsworth prison, where I would otherwise have been happy to read the graffiti on the walls, I tried reading a Jackie Collins book and couldn’t do it. I tried a few times but the Hollywood society that it described was such a spiritual and moral vacuum that, even compared to my current surroundings, I felt disgusted by it and had to put it down.

Like many prisoners I discovered The Ballad of Reading Gaol, and it was Dave, a career criminal and incorrigible armed robber, who recommended that to me. He also recommended the radio play of Les Miserables on Radio 4. I don’t think I could have managed to read the whole book at that time, but Dave the armed robber’s recommendation brought me to Victor Hugo.

I read Caesar’s Gallic Wars. That made a huge impact on me. The idea that Julius Caesar had written these words two thousand years before and I could just get them from the library and at least this brightness was not denied to me, was almost too much to bear. I studied Sociology, so I read Durkheim, Marx and conflict theorists. Sociological theory gave me tools to understand the workings of society that I had only seen in a mirror dimly up to then. It helped me to make sense of why the Queen’s cousin was in the same place as me and one of the (many) sons of the King of Saudi Arabia was two buildings along.

I read the Bible quite a bit when I was first on remand. A quiet Nun brought them around for those who wanted them. I was moved by the incredible spirit of love and devotion that shone from her every step. She was the only religious visitor who refused to carry a key. She never once locked the gates on us and she was always just as locked in as we were.

On literature, hope and change:

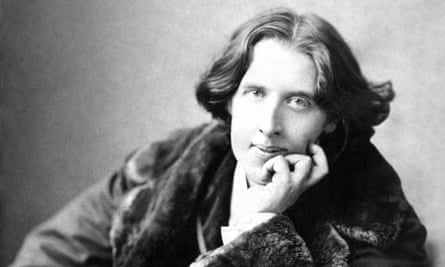

I would say all of them gave me hope. I’d loved Oscar Wilde from when I was a child. Reading the Ballad of Reading Gaol gave me a feeling of kinship with him. It also helped me to remember that a sane person would have to find a prison as monstrous as I did. It told me that I was not insane and that there was hope that others I would respect would see it the same way. It gave me hope.

What I loved the most was Homer’s Odyssey. Knowledge of "the classics", cultural capital was held so tightly by the intellectual class as a bulwark to justify their privilege, that it seemed to me, being a prisoner, an outcast among outcasts, daring to read those books and eat from the fruit of the tree of knowledge was an act of silent rebellion. I was working 12 hour days most of the time, and the lights were switched off at 10pm. so strangely, I didn’t have much time for reading. But I read all I could to expand my brain.

In the prison library I found a book on ‘Data Processing’. Reading it was like trying to drink an IT degree from a fire hose. It covered both business and technical subjects and just about blew my head off. I struggled with many of the concepts at first, particularly the deeper technology theory. I was completely alone trying to master hexadecimal maths and couldn’t understand the explanation of how they used this to compress data in computer code. I read it and read it over and again for a couple of hours straight. Finally I had my eureka moment when I suddenly got it and it all made sense. Literally two seconds later the prison guard pulled the switch and I was plunged into darkness. Jubilant, but unable to read even a sentence to confirm my understanding, I fell on my bed laughing at the absurdity of the situation.

On lessons learned:

I learned that, given the chance, literature will burst the bounds of race, culture and class. I remember one occasion where a young man, who had been educated by Benedictines at Ampleforth, and whose accent was more upper class than the Queen’s, was sent in a book by his mother. He couldn’t read it, it was too intellectual for him, so he passed on Umberto Eco’s ‘The Name of the Rose’ to a cockney wide-boy, a fading playboy with permed hair and a golden chain, who’d graduated from armed robbery to being a plumber, by far the greater crime. He read the book with great delight and passed it on with glowing recommendations to the more studious members of our company. I saw men reading and discussing books that I would never have dreamt of them every touching.

I am left with a raw wound of inverted snobbery against the literary elite. I railed against the suggestions that some made to send prisoners books to help them grow and change, to "learn from their experience" or stories that this inexperienced people imagined would be worse than the pain the prisoners were currently feeling and thus make them feel better. I can heartily recommend Jimmy Boyle’s "Pain of Confinement" for an idea of why merely the state of imprisonment is a pain that will be left in the DNA of most people who experience it.

So I would say, send everything you can. Bird watching, chemistry, model railways, psychic mysteries, history, let your mind run free. I was visiting someone who was on remand in Australia. He was independently wealthy and had ordered himself the entire back catalogue of the Nexus Magazine. He reported that copies of the magazine were in hot demand around the high security wing of the prison, especially the issues with detailed instructions on how to build your own Tesla levitation device!

The best antidote I found while I was there was education and access to books of all kinds that might bring some light into that darkness.

"I used to teach in a high security prison and they loved Othello"

Sandra Reston

I used to teach in a high security prison and they loved Othello – all about misguided decisions, so it seemed apt. For me becoming a teacher was difficult and non-conventional, so I started work at a Young Offenders Institution and then moved to a high security prison (top of the range high security). The prison that I taught at had two defined groups: the VP's, i.e. vulnerable prisoners because of their crimes, sex offenders, or because they were being bullied inside the prison; and the Mains, who were the more hardened criminals: murderers, violent crimes, more brutal activities.

In many ways they could identify with Othello the clever man, respected and bright who became a folly to his own failings and very much the tragic hero. It was the latter really that captivated them: both being a hero and being tragic. Perhaps it served as a vehicle for forgiving themselves for in many cases, their own irrationality, their own stupidity, their own greed. Some crimes are not in the realm of forgiveness but if one can find someone to relate to in some way then surely it would be Othello, who was highly regarded at the outset.

On literature and the experience of teaching in prison:

For the inmates literature was an escape. Not for all: for some, it was simply a time to get together and have an active discussion about persecution, unfairness all that is unjust in the world – a three hour session once a week to learn, to read and to understand how language created characters and how perhaps what they had ignored or dismissed at school made some sense.

I can confidently say I was never afraid or intimidated, and as much as it was their journey it was mine. Sadly the number of resources was limited and one had to very much make do with what one had and photocopy with a vengeance. I did manage to obtain books from friends and family – sometimes by donation – and found a very kind sales representative for a major publisher who used to give me her samples in exchange for a bottle of wine – invariably in a Tesco car park.

Interestingly and amusingly I can't begin to tell you of the number of times that at social events my husband (deliberately), to liven up a situation, would say something like "so how was it at the prison today?" which people either found shocking or interesting. I remember one situation, when we lived in a village, when a woman asked me what I did in the prison and when I said I was a teacher she patronisingly asked what was the purpose if they were criminals. This view holds in general, sadly. As a teacher in a secure institution one has to separate oneself from what the person did and simply teach the person.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion