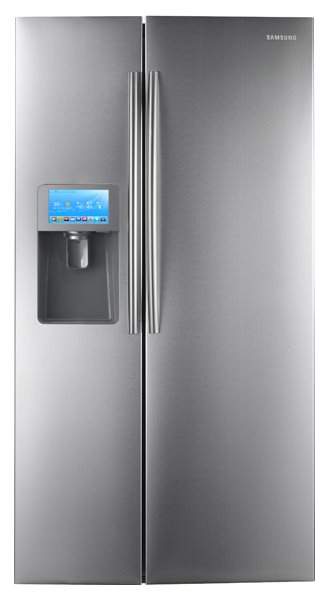

If you believe what the likes of LG and Samsung have been promoting this week at CES, everything will soon be smart. We'll be able to send messages to our washing machines, run apps on our fridges, and have TVs as powerful as computers. It may be too late to resist this movement, with smart TVs already firmly entrenched in the mid-to-high end market, but resist it we should. That's because the "Internet of things" stands a really good chance of turning into the "Internet of unmaintained, insecure, and dangerously hackable things."

These devices will inevitably be abandoned by their manufacturers, and the result will be lots of "smart" functionality—fridges that know what we buy and when, TVs that know what shows we watch—all connected to the Internet 24/7, all completely insecure.

While the value of smart watches or washing machines isn't entirely clear, at least some smart devices—I think most notably phones and TVs—make sense. The utility of the smartphone, an Internet-connected computer that fits in your pocket, is obvious. The growth of streaming media services means that your antenna or cable box are no longer the sole source of televisual programming, so TVs that can directly use these streaming services similarly have some appeal.

But these smart features make the devices substantially more complex. Your smart TV is not really a TV so much as an all-in-one computer that runs Android, WebOS, or some custom operating system of the manufacturer's invention. And where once it was purely a device for receiving data over a coax cable, it's now equipped with bidirectional networking interfaces, exposing the Internet to the TV and the TV to the Internet.

The result is a whole lot of exposure to security problems. Even if we assume that these devices ship with no known flaws—a questionable assumption in and of itself if SOHO routers are anything to judge by—a few months or years down the line, that will no longer be the case. Flaws and insecurities will be uncovered, and the software components of these smart devices will need to be updated to address those problems. They'll need these updates for the lifetime of the device, too. Old software is routinely vulnerable to newly discovered flaws, so there's no point in any reasonable timeframe at which it's OK to stop updating the software.

In addition to security, there's also a question of utility. Netflix and Hulu may be hot today, but that may not be the case in five years' time. New services will arrive; old ones will die out. Even if the service lineup remains the same, its underlying technology is unlikely to be static. In the future, Netflix, for example, might want to deprecate old APIs and replace them with new ones; Netflix apps will need to be updated to accommodate the changes. I can envision changes such as replacing the H.264 codec with H.265 (for reduced bandwidth and/or improved picture quality), which would similarly require updated software.

To remain useful, app platforms need up-to-date apps. As such, for your smart device to remain safe, secure, and valuable, it needs a lifetime of software fixes and updates.

A history of non-existent updates

Herein lies the problem, because if there's one thing that companies like Samsung have demonstrated in the past, it's a total unwillingness to provide a lifetime of software fixes and updates. Even smartphones, which are generally assumed to have a two-year lifecycle (with replacements driven by cheap or "free" contract-subsidized pricing), rarely receive updates for the full two years (Apple's iPhone being the one notable exception).

A typical smartphone bought today will remain useful and usable for at least three years, but its system software support will tend to dry up after just 18 months.

This isn't surprising, of course. Samsung doesn't make any money from making your two-year-old phone better. Samsung makes its money when you buy a new Samsung phone. Improving the old phones with software updates would cost money, and that tends to limit sales of new phones. For Samsung, it's lose-lose.

Our fridges, cars, and TVs are not even on a two-year replacement cycle. Even if you do replace your TV after it's a couple years old, you probably won't throw the old one away. It will just migrate from the living room to the master bedroom, and then from the master bedroom to the kids' room. Likewise, it's rare that a three-year-old car is simply consigned to the scrap heap. It's given away or sold off for a second, third, or fourth "life" as someone else's primary vehicle. Your fridge and washing machine will probably be kept until they blow up or you move houses.

These are all durable goods, kept for the long term without any equivalent to the smartphone carrier subsidy to promote premature replacement. If they're going to be smart, software-powered devices, they're going to need software lifecycles that are appropriate to their longevity.

That costs money, it requires a commitment to providing support, and it does little or nothing to promote sales of the latest and greatest devices. In the software world, there are companies that provide this level of support—the Microsofts and IBMs of the world—but it tends to be restricted to companies that have at least one eye on the enterprise market. In the consumer space, you're doing well if you're getting updates and support five years down the line. Consumer software fixes a decade later are rare, especially if there's no system of subscriptions or other recurring payments to monetize the updates.

Of course, the companies building all these products have the perfect solution. Just replace all our stuff every 18-24 months. Fridge no longer getting updated? Not a problem. Just chuck out the still perfectly good fridge you have and buy a new one. This is, after all, the model that they already depend on for smartphones. Of course, it's not really appropriate even to smartphones (a mid/high-end phone bought today will be just fine in three years), much less to stuff that will work well for 10 years.

These devices will be abandoned by their manufacturers, and it's inevitable that they are abandoned long before they cease to be useful.

Superficially, this might seem to be no big deal. Sure, your TV might be insecure, but your NAT router will probably provide adequate protection, and while it wouldn't be tremendously surprising to find that it has some passwords for online services or other personal information on it, TVs are sufficiently diverse that people are unlikely to expend too much effort targeting specific models.

Bringing planned obsolescence to our durable goods

But I think the issue is more significant than it might seem. First, I don't think this kind of enforced, premature obsolescence is good for anyone other than hardware companies. Replacing an otherwise perfectly good TV ahead of time just because its Netflix app is stale and no longer maintained is a reprehensible waste of resources. I would like to think that most people would recognize the wastefulness this represents and wouldn't ditch their TV just because its built-in Netflix app is out of date. But I'm confident that such thoughts have entered the minds of TV company executives, and they're hoping people do precisely that. You'll have a TV that works well for a year or two and then gets worse. If you sell TVs, that's good news.

Second, not all devices are as trivial as TVs. Cars are increasingly computerized. They're also really insecure in ways that unambiguously compromise safety. Smart cars (as distinct from oh so cute Smart cars), boasting their own Internet connections and rich software platforms, are only going to make this worse. Worse, it doesn't seem that car companies take software security seriously.

So if you want to participate in the Internet of things, your choice will be to send your perfectly good car to the crusher or let any bored hacker disable your brakes, probably by sending you a text message or something equally insane. The sensible option? Don't participate in the Internet of things. Take out the SIM, turn off the Bluetooth. Use the perfectly good satnav app that your phone has.

I don't want to sound all Luddite here. I got a new TV recently, and it's a smart TV. It's pretty unavoidable if you want a mid-range or better set. I love the idea of all our things being connected to the Internet, of having our media follow us, available and accessible from whatever device we happen to be using (though this only goes so far; I cannot fathom the appeal of smart fridges or washing machines). But a world of hundreds of millions of connected devices, all ignored and abandoned by their manufacturers, is not a healthy one.

As such, there are only two ways in which smart devices make sense. Manufacturers either need to commit to a lifetime of updates, or the devices need to be very cheap so they can be replaced every couple years.

If manufacturers won't commit to providing a lifetime of updates—and again, the experience with smartphones is, I think, instructive here—then these smart devices are a liability. Avoiding them entirely is troublesome, but we can certainly avoid using them. Ignore the smarts built into your TV. Don't add your account details to the Netflix app, don't hook them up to your networks, don't show them when the TV boots. Don't stick a SIM into your smart car. Don't play the manufacturer's game.

Instead, use smarts elsewhere. For example, instead of using the smartness in your TV (such that upgrading the smarts means upgrading the entire TV too, pointlessly wasting the LCD), you leave the smarts in a small set-top box like a Roku or an Apple TV. That will give you your streaming media and rich connectivity, but it's in a box that's relatively disposable. Sure, even that box won't be supported forever (though I daresay it will be supported for longer than a smart TV), but replacing it means replacing a small $99 gadget—not a thousand bucks of flat panel.

Listing image by LG

Reader Comments (236)

View comments on forumLoading comments...