Should Felons Lose the Right to Vote?

The poor and minorities are disproportionately locked up—and as a result, disproportionately banned from the polls.

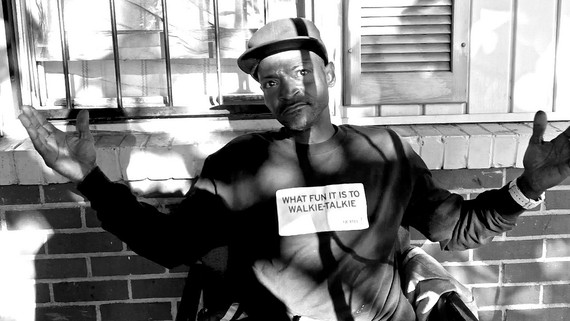

MONTGOMERY, Ala. — Richard is a felon, but he's not about to start assigning blame.

"I had a pretty decent childhood," is all he has to say about the rundown homes and apartments he moved between as a boy with his mother and grandparents and other assorted relatives in Montgomery. The fact that his mother, a nursing-home attendant, and grandmother, a maid, earned barely enough money to get by is irrelevant to him: One way or another, they got by. At least they both had jobs, which is more than he can say about his father, a veteran who lacked the wherewithal to be a dad.

How can poverty and "pretty decent childhood" coexist in Richard's mind? I want to know, as we sit down to a game of chess at the Montgomery Mission late one afternoon in October. I am there by choice, after all, and he with his "pretty decent childhood" is not. Three blocks to the west is Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, the tidy red-brick building with crisp white trim where Martin Luther King began preaching in 1954, when he was not quite Richard's age, 28.

The mission has all the ambience of an old-time parish home (unlike most of the city-run shelters I visited on my travels) and is presided over by the peerless Momma Donna, a church lady whose irrepressible warmth and hospitality are wholly out of proportion with her dainty frame. You won't have to wait two minutes before she deposits a heaping plate of Southern comfort food in front of you.

If there's irony in Richard's answer, he doesn't let on. Intergenerational poverty is Richard's status quo, neither good nor bad. Growing up in the land of MLK, it's all he's ever known. The same goes for just about everyone else he encountered growing up in the hood. "That's how Montgomery people is," he says with a shrug, trading his pawn for position.

A generation after the Montgomery bus boycotts purged the city and state of legal segregation, Richard was still riding de facto segregated buses and attending de facto segregated schools right through to senior year—schools where the best imaginable outcome for a youth of his complexion (dreams of NFL greatness aside) was to land a steady job in the trades.

Richard came very close. He was one transformer box away from getting fully certified as an electrician, courtesy Job Corps, and on his way to a lucrative tradesman's practice earning 20 bucks an hour. But a fear of heights on the final test—climbing the telephone pole to "mess with the high-voltage transformer"—left him in the lurch. "I could do everything else but not that, so they failed me …. That wasn't part of the plan."

His telephone-pole descent was soon followed by a headlong dive into illicit living on the street. As a teen, he had occasionally been picked up by the police for petty offenses—jaywalking, wearing his pants low, turning the volume up high—but now Richard started running with the wrong crowd and putting his mortality to the test.

It takes a bit of mental maneuvering to imagine this soft-spoken youth, with his chess sophistication and melancholy aspect, packing guns and robbing stores for fun. "It's crazy," he admits. "It wasn't even about the money." Having tried his hand at responsible living—"playing by the rules"—and come up short, Richard set out to reclaim his power by force. "It started becoming like a rush to me, like a drug to me," he recalls. "The shock when you bust in the store, the fear in people's eyes."

Fortunately, the police put an end to Richard's antics before he had the chance to shoot another person or get himself shot. He was tried and convicted without a fuss. Now, four years after the fact and recently released from federal prison, Richard makes no bones about serving his time in the pen. It's the stuff that happens after his release—what's brought him to this place—that has him in a state.

With an air of defeat, Richard describes the multiple attempts he's made since his release to line up work and a home—along with food stamps and public assistance in the meantime—and to reclaim his right to vote. The experience is always the same, he says: when he discloses his felon status, doors close in his face. "Some people don't believe in second chances," he says. "Once you're a criminal, always a criminal—they'll do anything to keep our people down."

"Our people," in this case, refers to the quarter-million Alabamans—and millions of other impoverished people across the United States—who have lost their citizenship status because of felony convictions. Most are nonviolent offenders and some will never set foot in prison or jail. Nevertheless, their ability to influence the laws under which they live is severely restricted from the moment they are found guilty of an offense, leaving them effectively powerless to change the socio-political conditions under which most of them live.

Although the Constitution is silent on whether people convicted of felonies should have their rights curtailed, most American states have chosen to restrict the franchise in modern times. Nearly 6 million people in 48 states—2.5 percent of the adult population—are currently ineligible to vote because of a prior conviction. Two-thirds of them have completed their prison terms, including two million people in 35 states who are prevented from voting while on probation or parole, and two million more in 12 states who continue to be disenfranchised once they have served out their sentence in full.

In the four most restrictive states—Florida, Iowa, Kentucky, and Virginia—all citizens who are convicted of a felony permanently forfeit the right to vote, regardless of the offense. Ten states even disenfranchise citizens convicted of misdemeanors while they are serving time.

The rise in felon disenfranchisement across the United States closely tracks America's War on Drugs and soaring prison population since the 1970s. There are 2.4 million Americans currently serving time behind bars in local, state, and federal institutions—one fourth of the total prison population worldwide and seven times more than in 1972. People convicted of possessing or selling illegal drugs account for one-third of all convicted felons, the largest single group. Other common felonies include property, white-collar, and driving-related offenses. Murderers and rapists make up just four percent of people behind bars.

Felon disenfranchisement is not randomly distributed across the population. The large majority of past and present felons who have lost the right to vote were raised and continue to live in poverty. According to an Urban Institute study, nearly eight in 10 incarcerated fathers earned poverty-level incomes of less than $2,000 in the month prior to their incarceration, and 40 percent did not have a full-time job—six times the overall rate of poverty at the time. Education counts as well: High-school dropouts are 10 to 20 times more likely than their college-educated peers to spend time behind bars, a fact which sociologists ascribe to diminished job opportunities for people with limited education in the United States today.

In racial terms, the disparities are greater still. African Americans constitute around 38 percent of disenfranchised people—five times the rate among non-blacks—because of significantly higher rates of searching, sentencing, and detention by the police. More than one in seven black men is officially disenfranchised nationwide, with rates climbing as high as one in three in certain states. Some scholars assign the racial disparity in felon disenfranchisement to higher rates of criminal involvement among black men—a contested claim—while most agree that there is longstanding institutional bias within the criminal-justice system. Whatever the cause, the consequences for second-class citizens of color caught up in the criminal-justice system are severe.

While losing the right to vote is simple in 48 states, recovering it after serving time can be a difficult and protracted process—assuming it is allowed at all. As a case in point, Richard explains that felons in Alabama permanently lose the right to vote if convicted of a slew of violent or sexual offenses, including sodomy and the production or possession of "obscene matter." Thanks to a 2003 state law, his crime of theft can now be forgiven once his parole is up by applying for a special pardon from the Board of Pardons and Parole.

Nevertheless, Richard doubts that he, a black man with a violent past, will be approved, and the official stats seem to bear him out: 7,700 ex-felons have had their voting rights restored under the 2003 law, or three percent of the quarter-million people who remain ineligible to vote because of past offenses. Nearly one in six black men in Alabama remains legally disenfranchised today.

As Richard further attests, the burden of felon disenfranchisement does not stop at voting for poor and minority citizens. Even after they have finished serving their sentence, former felons in Alabama and many other states are barred from serving on juries and denied access to essential government services, like food stamps, public housing, unemployment insurance, and welfare. In the case of food stamps and public housing—a particular concern of Richard's these days—the vast majority of states impose a lifetime ban on people with felony drug convictions receiving food or cash assistance, and a majority of states surveyed make decisions about housing eligibility based on arrests that never led to a conviction. Ex-offenders may also find themselves ineligible for educational benefits, military service, commercial driving licenses, gun possession, and other civil rights. Many forfeit their parental rights.

Most damaging to their long-term prospects, former felons face legal restrictions on employment in Alabama and 39 other states, where employers may base decisions not to hire—or to fire—employees on past arrests, regardless of whether the arrest led to a conviction. As a result, people with arrest records carry the social stigma that comes with criminality for the rest of their life. Meanwhile, those who do end up obtaining formal employment after serving time may find their wages garnished, in part or in full, to pay for their prison sentence or to make up for missing child-care payments while they were behind bars. The result is a permanent "second-class" status—what legal scholar Michelle Alexander terms the "American under-caste"—for current and former felons, irrespective of the nonviolent nature of most offenses.

When I bid Richard goodnight and set off to join a homeless camp to which I had been invited by another mission guest that afternoon, he leaves me with a warning I do not want to hear: "Don't let the police think you're homeless—they'll pick you up fast." Momma Donna agrees, adding that panhandling is against the law in these parts. She goes on to detail a pair of instances where homeless people she knew got locked up for weeks on end—"for no good reason"—while they awaited trial. "Once you're in, it can be real, real hard getting out," she explains. Shaken, I thank them for the warning and bid the pair goodnight.

An hour later, after dark, I arrive at the homeless camp with Eric, an unemployed contractor in his thirties and my host. I am relieved to find that the collection of tents and bedrolls and bags of goods or trash (I can't tell which) is safely tucked away in the woods outside of town—hence the long walk. "Police don't take notice here," Eric assures me.

As we're settling in for the night, I ask Eric for his perspective on poverty and the law. The anti-panhandling ordinance is first on his mind. "If they catch you, they'll lock you up anywhere from a couple days to a couple months," Eric says. He doesn't have much sympathy for folks who don't want to work, but not being able to find a job is a different story. "If we can't get a job and you won't give us a job to work, what the hell do you expect us to do?" he asks. "Do you expect us to go hungry and starve to death?" Voting is evidently far from his mind.

To illustrate the point, Eric tells me about a friend, a teenager in town, who recently spent 10 months in jail only to have his charges thrown out when his case finally came up in court. "He went to the Walmart store and stole a loaf of bread," Eric says. "They charged him with shoplifting and theft of property." Eric says that as soon as the kid was released, "he got straight on Greyhound" and left town. "Just senseless," he concludes, adding, "I woulda fought the hell out of that charge, don't care if they had me on camera nine." As for Eric's own journey from self-employed contractor and family man to where he is today, that's a story for another day.

Maurice, another homeless man in his fifties whom I interview the following morning, adds a story about panhandling of his own. He says he recently made the mistake of asking a Montgomery policeman for change in front of the store—"to put some gas in my car"—and was arrested on the spot for panhandling. "You know what the policeman did?" he asks, still incredulous. "He took me to jail! Locked me in jail for 21 days for asking for 50 cent!"

I could not verify the details of the accounts of Eric and Maurice, Richard and Momma Donna in Montgomery; I had not planned to investigate the "crime" of being poor. But as I completed my interviews and continued my journey, I was left with a nagging question: Is citizenship a luxury when poverty itself is treated as a crime?

This it the conclusion of a week-long series exploring the intersection of poverty and democracy in America. Read the rest of the series:

Poverty vs. Democracy in America: 50 years after Lyndon Johnson launched the War on Poverty, tens of millions of second-class Americans are still legally or effectively disenfranchised.

Should Felons Lose the Right to Vote? The poor and minorities are disproportionately locked up—and as a result, disproportionately banned from the polls.

Immigrant Voting: Not a Crazy Idea: Until the 1920s, many states and territories allowed non-citizens to cast ballots. Given their role in American society, it's worth reconsidering the practice.

Second-Class Citizens: How D.C. and Puerto Rico Lose Out on Democracy: Is there a connection between deprivation and a lack of federal representation? The people in territories without a vote sure think so.

Why Are the Poor and Minorities Less Likely to Vote? Even when America's underclass isn't formally stripped of its ballot, a slew of barriers come between them and full representation and participation.