They can want to. They can try. They can watch it, read about it; talk about it, blog about it. They can weep over its injustices, march in solidarity with its victims, use the right phrases and hashtags, even show homage for its music and culture. But just as non-parents can never fully understand the experience of actually being parents (forget the "my brother has kids" thing... it ain't the same), so, too, can whites never fully grasp the day-to-day, can't-turn-it-off, always-there experience of being black in America.

The unwarranted provocation, arrest and inexplicable jailhouse death of Sandra Bland has once again ripped the scab off a wound that never gets to heal in this country, a wound that bleeds with every event of racial profiling, injustice, bullying and bigotry, leaving us, for the umpteenth time, to parse and pull apart the seemingly endless conundrum of race.

Those who are bigots -- white or otherwise -- blather on about responsibility and bad behavior (valid issues frequently inapplicable), bandy false equivocations disguised as true rationale; raise their fists or argue their flags to proclaim superiority or victimhood, depending on perspective. Bigots have no shortage of language to express their small-mindedness; it's well-honed vernacular in a country still struggling with race even decades after constitutionally protected equality was established.

Those who are not bigots have a language, as well. They speak out, step up, march, and post signs; they struggle to find the right ways, the best, most effective, ways, to live against racism; to teach their children a different way, a more open-hearted, tolerant way to be honorable members of our diverse society. And yet, even they sometimes get pummeled for being "good white people" who are not doing enough, not saying the right things the right way. Their goodness is dismissed as self-congratulatory and hollow, lacking any full "understanding the black experience." Just reading social media threads can make those lines drawn in racial sand seem all the more insurmountable, and for those who are not bigots, that is dispiriting.

But it's also true that white people, no matter how nice, how good, how desirous of honest equality, can only understand so much of something they cannot viscerally experience. I know because I thought I knew... until I discovered how little I actually did.

I'm a child of parents born and raised in the city of Chicago, good, solid Catholic Democrats who supported civil rights, believed the golden rule's "do unto others," and authentically embraced the notion of "love one another as you love yourself." Though they moved us out to a lily-white farm town north of the city for reasons to do with wide, open spaces and family independence, they never faltered in exemplifying authentic open-mindedness when it came to diversity. As we got older and expanded our circles, my siblings and I had friends and dating partners of every race, creed and color, and no one was ever left out or excluded from our dinner table, a fact that nurtured us all to become adults emulating my parents' philosophy of equality and inclusion.

So I felt solid in my bona fides as a colorblind individual, educated to the history of race in America, horrified by many elements of that history, but clear about my own activist heart: a person willing to live righteously and go out on a limb to speak out and stand up against racism, a person as comprehending of the black experience as I could be from my very narrow perspective.

And narrow it was. Because as willing, able and motivated as I might have been, this simple fact is true: No white person can ever experience the experience of being black. The actual, visceral experience. That is, unless they conduct an experiment like John Howard Griffin did to write his 1961 book, Black Like Me, or as Pulitzer-Prize winning reporter, Ray Sprigle, did for his 1948 series of articles called "I Was a Negro in the South for 30 Days," (and I'm consciously leaving out the confounding racial dramatics of Rachel Dolezal). But most of us won't conduct those experiments, and so we can only guess at the realities from a certain racial distance.

But I did get close by association. For six years of the 1980s I lived with a black man in Hollywood, a musician who played drums in my band, inspired my foray into songwriting, and shared my crappy used car. And those six years became my reluctant, revelatory education into being black in America.

I wrote some about this relationship in a piece titled, Loudly Against the Language of Racism, and though one hates to quote oneself, let me share at least this:

Stopped by the police more times than I'd ever been before or since, we were harassed on such a regular basis I would actually shake when I saw a police car anywhere near. "Whose drums are those? Did you steal them? Where are you going/coming from? Is this your car? Why are you out so late? A couple that looked like you two robbed a store. Is there a pipe in your glove box?" (That one got me: Not ever having done drugs, I seriously thought he meant a sink pipe of some kind and wondered why on earth he thought I'd have one of those in my glove box!).

It was relentless. When we moved into our Hollywood apartment he was even stopped while carrying our TV up the stairs, landing him (and the damn TV) on the ground in full spread-eagle mode. The local law enforcement was dissuaded only after our very feisty neighbor came out and raised a ruckus.

I could go on, but my point is this: I, a "nice white girl" from a loving Midwestern family raised in a legacy of tolerance, had no idea, zero idea, that a black man in the 20th century, in a place as progressive as Los Angeles, at a time when diversity and interracial relationships seemed commonplace, and with two people who were not involved in criminal behavior, could be so egregiously impacted by a police culture rife with profiling, bigotry and harassment. I didn't know that, my white friends didn't know that -- the demographic of which I was a member didn't seem to know that. Because we white people don't experience that! At least, not unless we're in the company of black people.

After those years of tangential involvement, I still find myself anxious when a policeman approaches... and I'm a blonde, middle-aged white woman now living with a blonde, middle-aged white man! I can only imagine what level of anxiety is daily felt by the man I used to live with. Is felt by any black person. Was felt by Sandra Bland.

Tell me, is that the way any law-abiding citizen should feel when government officials sworn "to serve and protect" come into view? Of course not! And yet watching the absurd, appalling overreaction of trooper Brian T. Encinia to Sandra Bland's annoyance at being pulled over for minor cause, actions that led to the circumstances of her eventual death, makes clear just how dangerous and unpredictable being "stopped while black" can be.

And let's not parse about her "combative and uncooperative" behavior. Yes, we've all been taught -- all of us, whatever color -- to do what we're told and be properly respectful when stopped by the police, and certainly Bland's attitude could be interpreted as less than cooperative in that regard. But, please. Stories abound of white women who've gotten far sassier, even downright aggressive with police officers, who were not then dragged from their cars and strong-armed to the ground under threat of taser. The Bland video becomes, then, a case study in how a cop provoked the unnecessary escalation of a minor traffic stop, and considering the outcome of that stop, one cannot help but be outraged.

But beyond that commensurate emotion, what remains true for white people is the endemic non-comprehension of what it's like to have one's ethnicity precede you through a door. When I walk into a room, when I'm stopped by the police, when I go in for a home loan, no one knows or cares that I'm half-Greek, a quarter Irish, and a quarter German. They do not see a skin color that alerts them to the history of my immigrant grandparents, the trauma and tragedies of their ethnic struggles, or their challenges in assimilating into a new country.

When I walk into a room people see only a person, a woman. My ethnicity is all but ignored by virtue of my being white. My whiteness is neutralizing. It conveys no particular message, nothing to interpret. It triggers no response. No one judges my being white... at least no one who is white.

But when a black person walks into the room, is stopped by the police, or goes in for a home loan? The very first piece of information conveyed is race. Because it's seen, it's visible, it can't be hidden. And it comes with a litany of preconceived notions, conscious or unconscious judgments, and the weight of cultural branding. It will never be a non-issue:

"They were black." "It was a black man." "This black woman said..." "She's dating a black guy." "Why didn't they give that role to a black actor?" "How dare they give that role to a black actor!" "He's a black president."

You get the point.

With cops? You're white? Unless you're committing a crime right in front of their eyes, you're most often given the benefit of the doubt, the benefit of your race. You're black? You're dragged from your car for not putting a cigarette out.

When I was living with my black boyfriend and white friends made comments like, "He needs to get over his 'black thing'," or asked, "Is it possible he did do something to provoke the stop?", I knew I was standing on the great divide between our racial realities. In fact, what I learned during those six years was just how little the average white person can know.

It's not their fault. You can't know what you can't experience. You can intellectualize it, study it, witness it, and fight against it. But without black skin, you cannot fully experience it. The closest you can get (beyond the aforementioned writers and their experiments), is to live next to it. That proximity is illuminating.

So what are we to do, those of us who care about such things as fairness, equality and racial harmony? Lots of people have thoughts on this. Aaryn Belfer of the San Diego City Beat offers some suggestions in How to be an interrupter: A white person's guide to activism. Darnell L. Moore explains "8 Truths About Race That Every White Person Needs to Know" at Identities.Mic. Janee Woods delineates "12 Ways to Be a White Ally to Black People" in her piece at The Root.

There are countless suggestions and much to consider and learn. And we should learn; we must. However we do it. We will not all do it the same. We will not all do it with noise. Some will quietly create change while others storm the bastions. Both methods have merit. Let's just do it.

But let's also do this: not judge how it's done. Not presume those quieter methods are compliance or complacency; not presume that any open-minded white person is looking to "get a cookie" or a pat on the back. Not get caught up in litmus testing with hashtags, buzzwords or trending parlance.

If not enough is being done, or something better can be done, let's educate each other without disdain or denigration. Let's accept authentic support and solidarity without alienating it for its lack of perfection. Let's understand the truth that, while we may not be able to fully experience each other's realities, we can learn from each other, we can teach each other, and we can exemplify the world as we'd like it to be.

Because in the wake of all that we see in the news, all that's mourned in families and communities across this country; all that's inflamed by continued rancor and racial disharmony, our actions of sincere solidarity -- however flawed and imperfect -- will slowly, inch-by-inch, moment by moment, person-by-person, get us closer to that ideal world. Which will be something, once we get there, we can all experience.

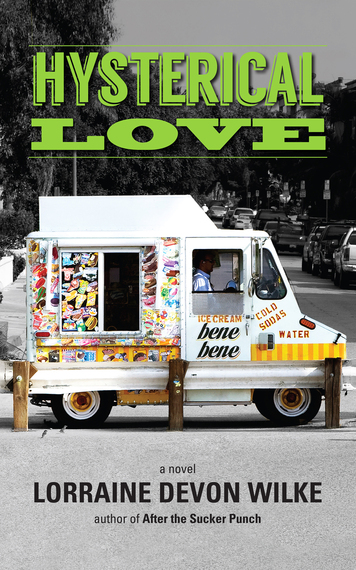

Follow Lorraine Devon Wilke on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Rock+Paper+Music. Access details and links to her other work at www.lorrainedevonwilke.com, and her novels, AFTER THE SUCKER PUNCH and HYSTERICAL LOVE at her author pages at both @ Amazon and Smashwords. Watch her book trailer for AFTER THE SUCKER PUNCH here, and be sure to follow her adventures in independent publishing at her book blog, AfterTheSuckerPunch.com.

Follow Lorraine Devon Wilke on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Rock+Paper+Music. Access details and links to her other work at www.lorrainedevonwilke.com, and her novels, AFTER THE SUCKER PUNCH and HYSTERICAL LOVE at her author pages at both @ Amazon and Smashwords. Watch her book trailer for AFTER THE SUCKER PUNCH here, and be sure to follow her adventures in independent publishing at her book blog, AfterTheSuckerPunch.com.

Related links:

An Open Letter to White Men in America

11 Things White People Need To Realize About Race

Mental Health Treatment Is A Privilege Many People Can't Afford