As citizens of the European Union prepare to elect a new parliament, they do so in a context marked by the onset of major instabilities in Ukraine and what is described as the most serious European crisis since the collapse of Soviet communism.

At an EU conference held in Vilnius in November Ukrainian President Yanukovych refused to sign the Association Agreement originally initialled in July 2012, and sparked off a wave of protests by demonstrators eager to promote a European affiliation and fearful of closer Russian ties. Their aspiration for stronger EU links and commitment to 'European' values only intensified as the authorities responded with rapidly increasing violence which resulted in the death in February of what came to be known as the Heavenly Hundred.

The fall of the government and the disappearance of the president from the scene was followed by demands for independence from Crimea and its annexation by Russia on March 21. This was followed by intensified activity on the part of pro-Russian groups, further signs of Russian aggression and continuing threats to the security of the east of the country, with a referendum on independence for the 'People's Republic of Donetsk' scheduled for May 11. Attempts to stabilise and de-escalate the situation, like the Geneva agreement reached between the US, Russia, EU and Ukraine on April 17, brought no concrete results. In what is a diverse, if not neatly divided Ukraine, the attachment to the west and desire for greater affiliation with the EU that contributed to sparking off the sequence of events is clearly not shared by all Ukrainians. In an extensively reported and widely debated sequence of events, this rapid escalation of events brought Europe and the west to the brink of what many have seen as a new Cold War.

In marked contrast, too, to the sentiments of many Ukrainians, particularly those in the west of the country, a large number of EU citizens feel increasingly alienated from 'Brussels' and the institutions of the Union.

A decline of trust in the EU

Euroscepticism and dissatisfaction with the EU is a major feature of the current pre-election mood. Since the onset of the economic crisis in 2008 there has been a steady and pronounced decline of trust in the European Parliament of around 30 percent through to 2012, significantly more than the growth of mistrust in national parliaments. A Gallup poll in January 2014 showed a further decline in EU approval ratings that is only likely to fuel the already strong showing of anti-EU parties and enhance their performance in the EP elections.

Recent polls, indeed, show that the number of deputies not affiliated to any European parliamentary group is likely to grow more than any other – and this group includes major far-right groups like the Dutch Freedom Party, Hungarian Jobbik and French National Front, the last of which is likely to increase its representation significantly if current projections are confirmed. The Greek Golden Dawn party is also likely to gain seats this time, all of which means that the far-right will probably win enough seats to form a new parliamentary group (Pollwatch 16 April 2014).

All in all, the fall of an unpopular, corrupt and ineffective government in Ukraine initiated by pro-EU demonstrators has not helped strengthen European values overall or slowed the decline in the popularity of the EU in the continent as a whole.

Arguably, the actions of the EU itself with regard to Ukraine have not been that positive, either. Against a background of some ambiguity concerning the background and the actions of the protestors themselves, it has also been asked why the EU accorded legitimacy to the new government so quickly in February when one of its first acts was to nullify the agreement recently negotiated with the participation of key EU representatives, which was intended to prevent civil war and provide the framework for a peaceful transition.

This raised just one question-mark over the 'competence and morality' of the EU and its policy-makers. The EU has been charged with being unequally committed to the Eastern Partnership, as clear differences of national interest between key players like Germany, France and the United Kingdom (not to mention smaller countries closer to the action, like Hungary and Slovakia) emerge when sanctions against Russia are on the agenda.

In line with previously expressed views, in The Washington Post (5 March 2014) Henry Kissinger pointed to the 'bureaucratic dilatoriness ' of the EU and the subordination of the strategic element to domestic politics which helped turn 'a negotiation into a crisis'. Even the influential European Voice (27 February 2014) suggested that while the EU states are much more democratic than either Ukraine or Russia, elections to the European Parliament itself have not always lived up the standards it espouses. As the crisis continued amidst growing signs of Russian aggression and incursions on Ukrainian territory, new signs of division emerged between different sectors of the EU that seemed further to undermine its effectiveness as a whole. Where, asked Carnegie Moscow Centre director Dmitri Trenin in The Observer (20 April 2014), were the signs of proper European leadership – and how long could it continue to outsource its foreign policy to the US?

None of this has had much influence on the EP election campaign, with the exception of some of the countries more closely involved with Ukrainian developments. The robust position of Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk and the active stance taken by Foreign Minister Sikorski during the crisis has helped strengthen support for the ruling Civic Platform – and contributed to the improving prospects of the EPP group as a whole in the new European Parliament.

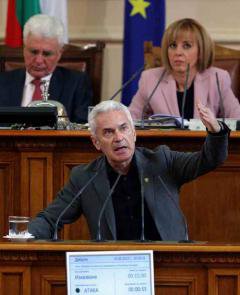

Volen Siderov, leader of the Bulgarian ultra-right party ATAKA, speaks in the Parliament. Demotix/Cylon 6. All rights reserved.In Bulgaria the electorate is divided over the fate of Ukraine and is caught between EU demands for sanctions to be imposed on Russia and domestic sympathies for its bigger Slavic brother, which also supplies the great bulk of its energy supplies. The balance of power in the Bulgarian parliament is, moreover, held by the extreme nationalist Ataka party, which has threatened to withdraw its support for the government if it endorses further sanctions. The EP elections are regarded as a key test for government survival.

Awareness of the mixed success of EU policy towards Ukraine and the weakness of EU's response to the crisis does not of course, mean that the actions of the former Ukrainian leadership or those of Russia and its leader, Vladimir Putin, should be condoned. The original demonstrations against the rejection by Yanukovych of the EU agreement soon turned into a massive protest against the spectacular corruption of the Ukrainian political elite and its poor record in government. The extreme violence used against the protesters further undermined the legitimacy of the incumbent authorities.

Russia too has clearly been in breach of the Budapest Memorandum, which guaranteed Ukraine's sovereignty as it gave up the nuclear weapons it had inherited from the Soviet period and to which Russia was a signatory in 1994. There may well be significant support for Putin's actions amongst the Russian-speaking population of Ukraine, but that hardly excuses the aggressive stance taken against a neighbouring state and the blatant pursuit of what is perceived to be Russia's national interest.

Ambiguities in the position of the EU and what precisely it can offer to its eastern neighbour in the absence of any promise of membership in the foreseeable future, the way it has pursued the Eastern Partnership, as well as the confused nature of its relationship with Russia which is a valued economic partner as well as problematic political neighbour, all contribute to the strengthening of the Russian position but do nothing to justify it.

As former EP President Pat Cox points out, Russian actions violate the fundamental values of the Council of Europe and breach OSCE principles on territorial integrity. These were basic issues of state sovereignty which had been thought to be settled after the wars of the twentieth century.

On the twenty-fifth anniversary of its first enunciation, Francis Fukuyama's argument for 'The End of History' still fails to offer a convincing way of describing the real world of politics. In the context of the Ukrainian crisis, as Cox notes, history has come up and bitten us again. Conceived in the heyday of Gorbachev's 'new thinking' and his drive to reform the Soviet Union (in a conversation recorded for an Open University course Fukuyama said that the main idea for the original lecture and article occurred to him during the Communist Party conference that opened in June 1988), his thesis was that the world was witnessing 'the universalisation of western liberal democracy as the final form of human government'.

This might have had some purchase on that unique and dramatically short period of change in Soviet Russia but seems to have little relevance to Putin's rule. Putin's famous pronouncement that the collapse of the Soviet Union was 'the greatest catastrophe of the twentieth century' hardly means that he intends to reassemble the territory of the former Soviet Union wherever possible – but in the context of the current Ukrainian crisis it is one interpretation that comes to mind.

But there is one sense in which at least parts of the idea of the 'universalisation of western liberal democracy' have particular relevance to the countries of the former Soviet Union. Gorbachev's reforms were halted by the August 1991 coup of communist hard-liners, which was then followed by Yeltsin's suspension and later banning of the communist party throughout Russia.

With the elimination of the core of the system the Soviet Union itself soon collapsed. In the absence of anything like autonomous state structures what was left was the economy, and the opening up of the former Soviet space to global capitalism provided possibilities of quite different forms of governance. If not liberal democracy, there was the clear prospect of another variant of liberalism. Rather than the universalisation of liberal democracy, it is the globalisation of economic neo-liberalism that has been the most common feature of the post-communist world (although, fortunately, liberal democracy has not been absent either – most obviously, it should be noted, in the post-communist states that have become members of the EU).

The economic devastation that accompanied this process has been particularly severe in Ukraine, with income per capita falling by nearly 60 percent between 1990 and 2000. At the end of 2013 it was still more than 20 percent below the 1990 level, a pertinent contrast with Russia where income by this stage was 20 percent above the level of 1990. EU assistance did little to improve this situation, as domestic conditions and problems of corruption meant that Ukraine received no more than one third of the funds earmarked for it.

All in all, EU funds contributed the equivalent of just 0.1 percent of Ukraine's national budget. It is not difficult to imagine the impact these developments have had on political attitudes. A major part of this process, too, has been the privatisation of state assets, the emergence of spectacular levels of inequality and the formation of a small group of powerful oligarchs.

Such people lie at the heart of the Ukrainian political system in the same way they do in several other post-Soviet states. This has been just as true following the departure of Yanukovych and the formation of a new government, whose political base lay more in the west of the country. In the east it was natural, James Meek reported in The London Review of Books (20 March 2014), for the new Kiev government to seek the support of local oligarchs and appoint them to key leadership positions in cities like Donetsk and Dnepropetrovsk.

Another Cold War?

But if this unappealing outcome of the introduction of neo-liberalism to the lands of the former Soviet Union, even when accompanied by regular elections, does not look like liberal democracy in any normal sense, neither does it provide the conditions for a return to Cold War relations as they prevailed in this part of Europe after World War Two.

An important part of the Cold War system was ideological competition and a radical incompatibility of systemic values between East and West. Quite clearly, private property and personal wealth are no longer an anathema in either Ukraine or Russia, even if their distribution is highly skewed. Their elites and ruling groups enthusiastically participate in transnational economic ventures, make use of lucrative opportunities wherever they present themselves, and consume the same goods and services as the rich in western countries.

Whereas the Cold War implied a major standoff between the two camps and limited, closely controlled, interactions, there are now extensive structures that underpin highly developed forms of global integration which, further, make the imposition of economic sanctions on Russia a realistic way of reinforcing western displeasure at current Russian actions.

The apparent intensification of power politics in terms of the vigorous pursuit of national or state interests by greater or lesser powers, combined with heightened military tension, is something else – even if it is reminiscent of the superpower rivalry of the Cold War period. The role of NATO is of key importance here, particularly in view of the questionable response of the EU in this context. With clear evidence of Russian aggression and the infringement of Ukrainian sovereignty it was a natural response for NATO, as a defensive alliance, to adopt a more active posture and, for example, to reinforce the presence of American forces in Poland and the Baltic states (which actually share a border with Ukraine). As was evident on many occasions during the Cold War period, however, the development of effective defence could mean taking up forward positions that the antagonistic power might well perceive as aggressive, which might or might not be the case.

NATO is, too, essentially the same organisation it has been since its establishment in the early post-WW2 years, whereas the former Warsaw Pact was dissolved in the early 1990s. The sensitivity of post-communist Russia to the role and actions of NATO is a factor that can be significantly underestimated in the present crisis, and may be associated with Russian feelings of historic vulnerability on its western border and fears of alien encirclement (although this is a view firmly dismissed by others who point out that Russia has tolerated NATO members like Poland and Estonia on its doorstep since 1999 and that it is the advance of democracy and the rule of law in Ukraine that is really perceived as threatening).

During the early stages of the first President Bush's presidency there was an understanding that democratisation in East-Central Europe would not involve the expansion of NATO. This changed during the 1990s for a number of reasons, not least because some of the newly democratised Central European countries were committed less to membership of the EU than to integration more generally with 'Euratlantic structures', meaning, of course, NATO as well.

West European failures to guarantee their security during the 1930s were not forgotten, and the EU could not promise this kind of protection either then or now. There was some sensitivity on the part of US administrations to this factor. The formation of the G8 under Clinton with Russian participation in the original grouping was intended to signal Russian integration in the international community as a quid pro quo for the expansion of NATO into the former Soviet Eastern Europe. Few, if any, were able to remember this as the western powers decided not to participate in the G8 Sochi summit as one of their first sanctions following the Russian annexation of Crimea. Views also changed during the G.W. Bush presidency. In the spring of 2008 Bush controversially changed the agenda and designated Ukraine and Georgia as potential NATO members, which opened a direct path to the unequal and short-lived war between Russia and Georgia later that year.

There are signs that the Bush view continues to prevail during the present crisis, and on April 1 the foreign ministers of the NATO countries confirmed that the alliance would continue to expand despite Russian protests although Ukraine, unlike Georgia, was not explicitly mentioned.

The message, however, was clear and, following NATO's suspension of cooperative activities with Russia, the charge that it was returning to the rhetoric of the Cold War was not without substance. Underlying this, too, may be domestic US dissatisfaction with President Obama and the desire to return to more robust US leadership in the international arena that is harboured in some quarters, not least the defence lobby.

In this context the current western response has tended to emphasise the role of NATO and the US in the crisis in relation to that of the EU, which has shown signs of hesitation and division in its attitudes both to Ukraine and Russia. But in some ways this only mirrors the position of the EU overall, and reflects the strains and weaknesses that contribute to the emergence of such a negative mood among much of the electorate for the new European Parliament.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.