Where Do Firms Go When They Die?

Companies can't live forever, and the average lifespan of a publicly traded company is dropping. The good news is they become other companies.

In the classic economic paper The Nature of the Firm, Nobel economist Ronald Coase wrote about why firms exist. Coase's argument was that firms lower the costs of producing goods and services, because it's easier to coordinate people and projects when everything is done under one roof. But today, communications technology has dramatically reduced the costs of having certain jobs done out-of-house. Will firms live as long as they once did?

It seems not: Richard Foster, a lecturer at the Yale School of Management, has found that the average lifespan of an S&P company dropped from 67 years in the 1920s to 15 years today. Foster also found that on average an S&P company is now being replaced every two weeks, and estimates that 75 percent of the S&P 500 firms will be replaced by new firms by 2027.

With so many firms dying off at a faster rate, what is becoming of them? Are they just going belly up? A new report from the Santa Fe Institute says quite the contrary: American companies die to create new companies or become a part of another company. Looking at a database of 25,000 companies from 1950 to 2009, the group of researchers employed mathematical models from theoretical ecology to look at the the lifespans of American companies. They found that publicly traded companies die off at the same rate, regardless of the firm's age or what sector it's in. In their dataset, they found that most firms live about 10 years and the most common reason a company disappears is due to a merger or acquisition.

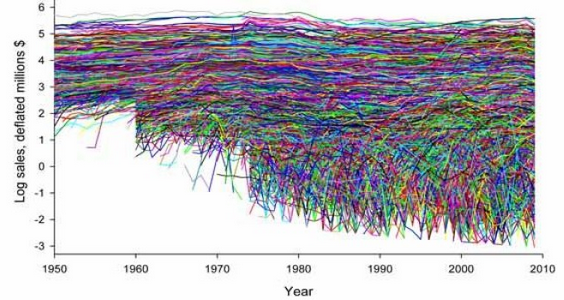

This graph shows the sizes of 30,000 publicly-traded companies, with sales leveling off as companies reach maturity.

The researchers at Santa Fe Institute note that their findings are different from what you would see in Europe and Japan. The latter is home to more than 50,000 companies that are over 100 years old (including this 1,300-year-old inn), though these ancient family-run businesses are also starting to face mortality in light of Japan's updated bankruptcy legislation. Foster, on the other hand, has called for American firms to embrace "creative destruction" rather than fight it.