Editor’s Note: Penn Jillette, a writer, television host and frequent guest on a wide range of shows, is half of the Emmy Award-winning magic act duo Penn & Teller. He produced and appears in “Tim’s Vermeer,” a new film. For more on the story of the Beatles’ arrival in America 50 years ago and its lasting consequences, check out coverage of “The Sixties: The British Invasion.”

Story highlights

Penn Jillette: As a kid, I thought the Beatles recorded their songs without a hitch

He says bootleg recordings showed him the mistakes and rigors of creative process

Genius doesn't mean doing everything right the first time, he says

Jillette: My friend Tim Jenison showed process in detail as he tried to paint a Vermeer

When I first heard The Beatles, as a child, I thought they walked into the recording studio with a genius idea and they executed that idea perfectly.

Every note, every word, every la da da dadada was planned and just had to be laid down on wax. The recordings were perfect. The Beatles were geniuses and that’s how geniuses created works of art.

I had never met anyone who created real music and I figured musicians had ideas for sounds in their heads and then performed them. That was the job and to do it you had to be a genius.

Then I bought my first bootleg record. Stamped on the plain jacket were the words “Kum Back” and the record store had it filed under Beatles. I kind of knew what I was buying. I knew these were recordings of The Beatles that The Beatles hadn’t wanted released.

I was a Beatlemaniac: Remembering The Beatles’ American invasion

There wasn’t even shrink-wrap to unseal with my thumbnail before I put it on the turntable. The song titles weren’t listed on the label, there was just a picture of a pig and a hole in the record that wasn’t even centered. This was dirty and wrong.

It turns out the bootleg of “Kum Back” I had was not even the real bootleg of the Glyn Johns acetate. It was another collection of Beatles stuff misnamed to cash in on the first Beatle bootleg. In my town we got counterfeit bootlegs.

As I turned up my mom’s record player loud what I heard changed my life. I heard The Beatles making mistakes. I heard them fumbling around to find their genius.

It was mostly outtakes from “Let it Be.”

“Let it Be” was supposed to be funkier, dirtier, and more live sounding than “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” but my inexperienced ears didn’t understand that.

The released album, even with “Dig it” and “One After 909” and Phil Spector’s inappropriate production was perfect to me. Even the giggles on “Let it Be” had seemed planned to me. But this bootleg had Paul singing out of tune!

It had versions of the songs that were different. It had The Beatles trying different tempos, different lyrics and different ideas. It had The Beatles fighting. I heard The Beatles failing. I heard The Beatles working.

Video: The Sixties: The British invasion

I still believe The Beatles started with ideas. They had feelings in their hearts and thoughts in their minds they wanted to express. But learning that they didn’t have perfect blueprints from their genius was a revelation. It inspired me to start to practice and rehearse the stupid ideas that I had.

Armed with nothing more than the knowledge that The Beatles had to work on the records, I started learning to juggle and do magic. It’s been way more than 20 years ago today and I still haven’t finished my juggling/magic Sgt. Pepper’s, but I’m still working.

I’ve met a lot of musicians, and they bang around a lot before they come up with the finished track, or the finished composition. I’ve learned that writing books, essays, and magic patter is mostly editing. No matter how clear the idea is, you have to monkey with it. You have to work.

Even Bob Dylan crosses things out and starts again. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has his notes on display to prove that. (Although I still believe it’s possible that Dylan fabricated those mistakes after the fact just to test our faith, like some creationists believe god created confusing fossils.)

In comedy Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton are often held up as two ends of the discovery/vision continuum. Lore is that Chaplin would monkey around on the set trying all sorts of things until something seemed right and Keaton supposedly showed up just to shoot the scene he already had in his head. I’ve always respected Keaton so much more than Chaplin – I like the idea of having an idea – but I’m sure there are Keaton outtakes. Keaton didn’t just risk his life and break his bones – he also had to work. He must have run down some dead ends.

I understood the idea of work in music, comedy, movies, writing, performance, and certainly juggling and magic, but the fine arts still had that wall of genius separating pure inspiration from work. I would see studies and sketches in museums, but even those seemed perfect. I thought the fine arts were something else, something different, a pure kind of genius.

Then about five years ago my buddy, entrepreneur and inventor Tim Jenison, told me he was going to paint his version of Vermeer’s “The Music Lesson” in his warehouse in San Antonio. Tim reckoned that Vermeer didn’t just get a perfect photorealistic image in his head and move it to the canvas with a steady handful of talent. Tim figured that Vermeer had used a machine and a lot of hard work.

Tim was going to recreate a machine like that and with no experience or talent for oil painting, Tim was going to try to do his own Vermeer.

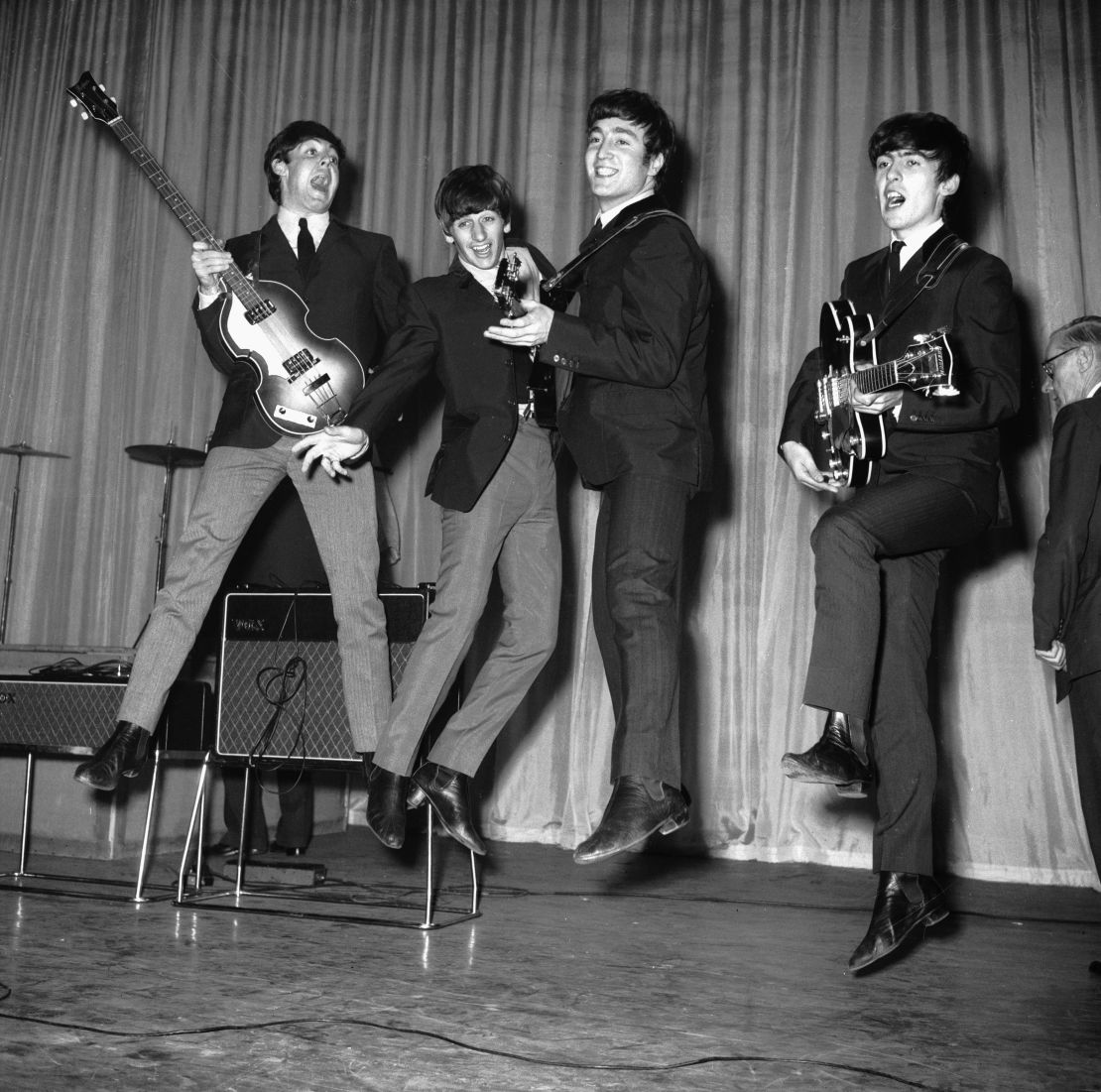

This wouldn’t be just four Liverpudlians sitting around in a room with guitars, drum and a piano serving the muse. Tim would first have to tear down the wall of his warehouse in Texas to put in windows for the proper light, build all the furniture himself to recreate Vermeer’s room from the 17th Century, grind his own lenses, grind his own 17th century style pigments (many of which are illegal today because they’re so poisonous), mix his own paint and after all that and more, then he could start the backbreaking and mind-numbing work of painting with his machine. It would cost him more money and man-hours than all the Beatle albums put together.

I told Tim we had to document his trying to paint a Vermeer, and I convinced Teller to direct a movie that would be Tim’s bootleg “Kum Back” to Vermeer’s perfect “Let it Be.” I love Tim and didn’t think I could respect him more than I did before he started this project. I was wrong. Tim is The Beatles. Tim is Vermeer. Tim is a genius.

“Tim’s Vermeer” didn’t diminish my love, respect, enjoyment or awe of Vermeer’s paintings. I still believe in genius. But, for better or worse, all geniuses have to work their asses off.

There will be an answer, but you can’t just let it be.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Penn Jillette.