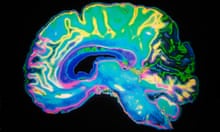

“Breakthrough”, “new hope”, “disease could be prevented by immune system tweak”. Newspapers this week trumpeted the latest research into Alzheimer’s disease. Scientists have found a drug that prevents the illness, and slows its course in those already suffering. The caveat, however, is that these Alzheimer’s patients are mice.

We are a long, long way from discovering if what’s good for rodents is good for us. But it’s hard to suppress a quickening of the pulse, particularly if, like me, you’ve lost close relatives to the disease. I remember the excitement over Aricept, a drug thought to delay progression, in the 90s. The Alzheimer’s Society now says that it can improve symptoms for six to 12 months in 40% to 70% of patients. Hardly a magic bullet.

Do we overhype cutting-edge research? We love the idea of a eureka moment, but the danger of following every move in the laboratory is that cynicism sets in when promising results fall at the next hurdle, or contradictory evidence turns up. As the cancer writer Henry Scowcroft explains, animal models are the start of a process that can take many years.

What’s the solution? Well, we can’t hide studies from the public, he says. After all, they’ve paid for them. But if people had the tools to place the work in context – knowledge of the different phases of clinical trials, for example, an appreciation of the limits of drug therapy (Scowcroft says it’s good, old-fashioned surgery and radiotherapy that cures most cancers), we might be able to understand what those mice are really telling us.

It just clicked

A less urgent medical puzzle appears to have been solved once and for all by a team of Canadian researchers. MRI scanners were used to observe finger joints as they “clicked”, showing that the noise is made by bubbles forming in fluid that lubricates the knuckles.

It’s a mystery that’s exercised the curious for years – as the Guardian archives reveal. In the years before Wikipedia, the paper’s Notes & Queries column was an indispensable guide for the kind of people who now spend their evenings chasing links until they find they’ve wasted the last hour reading about the war of Jenkins’ Ear.

In June 1991, a parent writes: “Our son insists on cracking his fingers. What makes the noise inside his hands, and is he likely to suffer in the future?” The bubble theory is then adduced by Brian Ford, of London SW1, who also advises against the habit. But in February 1994 it crops up again: “What makes my knees crack?” “There are three sources of noise from a joint – arthritis, tendon flick or gas bubbles,” replies a confident-sounding Steve Seddon, of Newcastle-under-Lyme. Who needs MRI when you have the collective wisdom of Guardian readers?

Mind the gap

My cycle to work has been made more picturesque by the demolition of an office block on Borough High Street, in south London. With four storeys suddenly removed from the streetscape, a new view of St Paul’s Cathedral has opened up, looming much closer than I would have guessed. It feels as if the perspective of an earlier age has been reinstated – with the great dome dominating the skyline as it must have done for centuries.

I love it when gaps in the city’s fabric open up like this and sometimes wish they could be permanent. There’s no moral case for keeping stretches of an overcrowded capital free of buildings – but these short-lived urban lungs always seem like a breath of fresh air.