In a recent revelation by OMG Chrome and the developer of the Chrome extension Add to Feedly, it came to light that Chrome extensions are capable of changing service or ownership under a user’s nose without much notification. In the case of Add to Feedly, a buyout meant thousands of users were suddenly subjected to injected adware and redirected links.

Chrome’s regulations for existing extensions are set to change in June 2014. The changes should prevent extensions from being anything but “simple and single-purpose in nature,” with a “single visible UI surface” in Chrome and a “single browser action or page action button,” like the extensions made by Pinterest or OneTab.

This has always been the policy, per a post to the Chromium blog back in December. But going forward, it will be enforced for all new extensions immediately and for all existing extensions retroactively beginning in June.

Given how Chrome’s system of updates, design restrictions, and ownership seemed to have gotten ahead of itself, we decided to take a look at the policies of other browsers to see if their extensions could be subjected to a similar fate. While Chrome isn’t the only browser where an Add To Feedly tale could be spun, it seems to be the most likely place for such an outcome.

Firefox

Mozilla’s Firefox differs from Chrome in that it has an involved review system for all extensions that go from developers to the front-end store. Reviewers will reject an extension if it violates any of the rules in Firefox’s extension development documents.

One of these rules is “no surprises”—an add-on can’t do anything it doesn’t disclose to users, and existing add-ons can’t change their functionality without notifying the user and getting their permission.

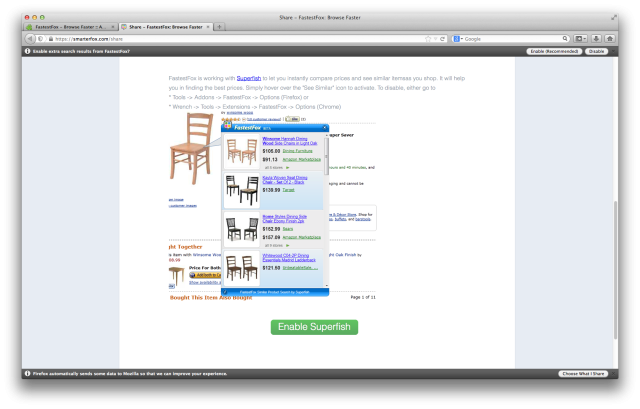

Firefox puts add-ons with “unexpected” features, like advertising that supports the add-on financially, into a separate category. Users have to explicitly opt-in to these features, says Jonathan Nightingale, vice president of Firefox. “This means that in these cases, users will see a screen offering them the additional features,” says Nightingale. One example is FastestFox, which pops a tab at first install asking the user to enable ad injection from Superfish.

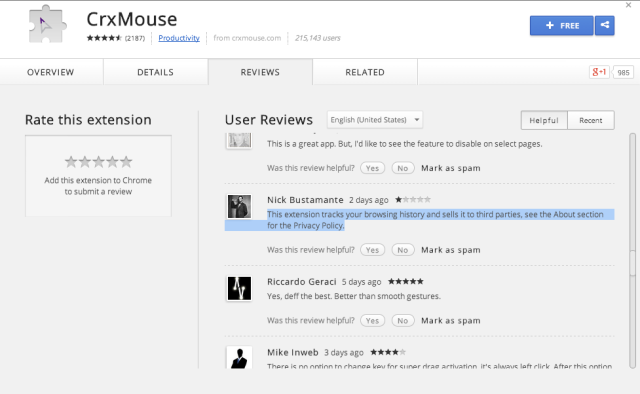

It's how developers implement these opt-in screens that could provide for a possible loophole; the addition of advertising might be obscurable by language, and data tracking could be, too (it's permitted under Firefox’s rules, but it must be disclosed in a privacy policy). Still, the review policy and need for opt-in for these more pernicious features both help prevent users from having new functionality sprung on them.

Safari

Safari has extensive design documents for its extensions but no central clearinghouse for them like other browsers. Apple keeps a “gallery” of a chosen few extensions that must meet certain regulations, but these represent a small fraction of the extensions available.

Data tracking of an extension’s users is possible, per the design docs, as is ad manipulation. Unlike Chrome, but like Firefox, the download and installation of Safari extension updates must be manually approved by the user. There are no regulations for disclosing functionality changes or changes of ownership, however.

Internet Explorer

Microsoft’s browser absolves itself of responsibility for add-ons on a support page where it states, "While add-ons can make your browsing experience better by giving you access to great Web content, some add-ons can pose security, privacy, or performance risks. Make sure any add-ons you install are from a trusted source." Add on at your own risk.

Like Apple, Microsoft maintains an exclusive gallery of vetted add-ons. The company encourages extension makers to get user consent for unexpected add-on functionality, but it doesn’t require it or block extensions that don’t do it. Markup-based extensions can only be installed from within the browser, and therefore these must have the user’s explicit consent according to Microsoft.

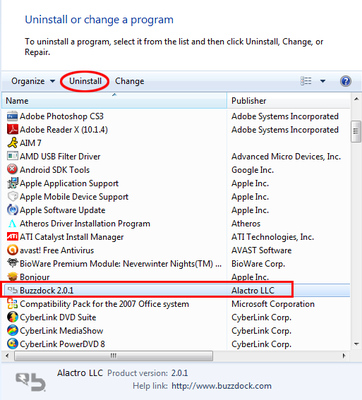

Other than this infrastructure, nothing prevents IE add-ons from doing things like injecting ads or redirecting a browsing experience (remember, this was the former home of the invasive toolbar add-on). IE10 does have an add-on management window, but some add-ons, like the ad-injecting Buzzdcock, have to be removed as if they are full-fledged applications.

Opera

The latest versions of Opera are able to use Chromium extensions, but unlike Chrome ones, they get a review process that’s similar to Firefox’s. Most importantly in Opera, there are restrictions on the types of scripts an extension can run and how they handle ads.

Andreas Bovens, head of developer relations at Opera Software, told Ars in an e-mail that Opera doesn’t “allow extensions that include ads or tracking in content scripts, so extensions that, for example, inject ads inside webpages the user visits are not allowed.” Extensions can, however, have ads in their options pages or in the pop-up that is triggered by their button in the browser’s interface.

Every extension gets a review, and the review team takes special care to suss out the nature of any obfuscated JavaScript code. If some of the code is obfuscated, reviewers ask the developers for the unobfuscated code to look at as well as a link to the obfuscation tool. That way “we can check that the input and output indeed match,” Bovens says.

“When an extension’s ownership is transferred or the extension is updated, it’s subject to the same rigorous review process as an extension that’s being submitted for the first time,” according to Bovens. An extension that goes from having no ads to injecting ads, as some Chrome extensions do, “simply would not pass [Opera’s] review process,” Bovens says.

Retiring to the not-so-Wild West?

While Chrome extensions may have a better ideology than those of some other browsers, the breadth and depth of functionality that Chrome extensions can have without any kind of review process means that Chrome users’ trust can get taken for granted. It’s similar to the Google Play app store, in that way: pretty much anything can make it to the market, but enough user complaints can get it taken down, as in the case of Add to Feedly and Tweet This Page.

Based on policy and practice, users who heavily rely on extensions or have been made wary of them by developers’ recent transgressions may be safer on browsers like Firefox and Opera, where regulations are a bit stricter and there are people to police them. But there can be downsides to a vetting process, too, mainly in terms of rate-limiting iteration and improvements, so it’s a matter of weighing options.

Update: In a statement from Google, the company tells Ars that it uses an "automated, proactive review process" to assess extensions before they go into the store and the company "conduct[s] ongoing scanning" of available extensions.

reader comments

75