On December 22, 2012, hedge fund manager Bill Ackman gave a three-hour presentation outlining why he believed Herbalife — a 33-year-old, multibillion-dollar, publicly traded nutritional supplement company — was actually an illegal pyramid scheme. The company’s business practices were unfair, he said; they targeted the poor and the uneducated, and they blatantly went against established protocols in the United States against endless chain selling.

Ackman argued that regulators at the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) should immediately shut Herbalife down. He was so confident in Herbalife’s illegality that his hedge fund, Pershing Square Capital Management, placed a $1 billion bet against Herbalife’s stock price. Federal regulators would soon step in, he predicted, and Herbalife’s value on Wall Street would drop to zero. Instead, the company's stock price is as high as its ever been and Ackman's bet looks like a bust — but now he's trying again to make good on his billion dollar gamble.

Ackman's assault on Herbalife is unprecedented

Though Ackman is a well-known "activist investor" who has publicly shorted companies in the past, his assault on Herbalife was unprecedented — a massive, sweeping series of bold allegations backed by an unbelievably large wager. Media all over the world — including The Verge — flocked to tell the story. This was partially because of how much money Ackman put behind his gamble. It was also because of Ackman’s apparent motivations. His company stood to make a dizzying amount of cash if Herbalife went down, but he said that didn’t matter; he’d give his billions in Herbalife proceeds to charity. Ackman’s short sale was as much a crusade against a company he believed was a scam as it was a stock-market ploy. He wasn’t without his critics, though: a prominent Northwestern University researcher accepted Herbalife support to argue the company isn’t a scam, a Nobel Prize winner backed Herbalife, and Ackman has faced relentless jeering from Wall Street.

That jeering may not be wrong. A year in, Ackman’s bet looks like a conspicuous loss. Though there’ve been rumors of an FTC investigation into Herbalife, it hasn’t happened. And without the heft of serious regulatory actions, Ackman’s presentation is only a suggestion from a Wall Street investor. FTC public affairs officer Betsy Lordan told The Verge, "the Federal Trade Commission has no comment to make regarding Mr. Ackman's presentation." In response to the FTC’s inactivity, Herbalife’s stock value has risen to new heights. After an initial price drop late last year, Herbalife’s stock value rose consistently, hitting a record high of $74.94 per share last month — more than triple the value of its lowest price in the wake of Ackman’s December, 2012 presentation. He’s lost half a billion dollars so far in the transaction.

Herbalife's stock has been climbing

Seemingly unfazed, last week Ackman reiterated his belief that Herbalife is a pyramid scheme. He gave another long presentation — one he called "Robin Hood In Reverse" — outlining the reasons why federal regulators should step in and close Herbalife’s doors for good. It’s, again, a searing presentation — a statement with deep supporting arguments, showing that Herbalife steals from the poor to pay the rich. It even cites federal policies that he says Herbalife’s business model clearly violates.

So why hasn’t the FTC stepped in?

The umpires

Herbalife is a multi-level marketing company — an MLM. Like Amway (which sells household items), Nu-Skin (which sells dietary supplements and beauty products), and Avon (which sells beauty products), Herbalife’s goods are not available in retail stores. Instead, its products are sold by non-employee distributors, who can sell to their friends or family, or perhaps use the internet and media to recruit people outside their immediate circle. These distributors are paid based on how much they sell, how many additional people they recruit as distributors, and how much those distributors sell and recruit.

The FTC has a long history of failing to clarify the issue

MLMs have been controversial for at least the last 50 years. Mostly, that’s because it’s difficult (and some say impossible) to differentiate legal MLMs from illegal pyramid schemes. The FTC has a long history of failing to clarify the issue.

In 1979, an FTC administrative law judge ruled that Amway was not a pyramid scheme because the company required its distributors to sell 70 percent of their products at retail or wholesale — meaning, not to other Amway distributors for their own consumption. There was some confusion in the wake of that decision, but the spirit of that rule represented something close to a pyramid-scheme definition. It’s known in the MLM industry as "the 70 percent rule."

"Selling to distributors is not evidence of an MLM company operating as a pyramid scheme in and of itself," says Oz, the shadowy figure behind the longstanding website Behind MLM. But "if this activity dwarfs retail activity, it's evidence that a company is surviving only on the purchases by recruited distributors." This demonstrates "a lack of value in the product without an attached income opportunity," he says. "A lack of retail viability is a hallmark of a pyramid scheme."

"A lack of retail viability is a hallmark of a pyramid scheme."

Herbalife, like many other MLMs, has not revealed how much of its revenue comes from retail sales versus sales to distributors. Oz is a little baffled by this. "Strong retail revenue figures would kill pretty much all of the pyramid-scheme allegations dead in the water," he says. Yet Herbalife has failed to reveal its retail figures. And the FTC hasn’t yet forced it to. It also hasn’t explicitly stated that MLMs are required to follow the 70 percent rule.

William Keep, dean of The College of New Jersey’s business school and outspoken analyst of MLM sales data, believes that "markets work best if they're well regulated." And with MLMs, "it’s possible to develop regulations that will weed out bad behavior as long as those regulations are clear and enforced with some consistency and rigor." However, he says, "that hasn’t been happening."

The result is that MLM prosecutions are few and far between. And they tend to take forever. The 1979 Amway decision took four years to complete, for example, and didn’t result in any kind of punitive action against Amway until 1986, when the FTC fined the company $100,000 for failing to follow a rule about earnings disclosures.

"Regulators tend to think in terms of decades"

"Regulators tend to think in terms of decades," Keep says. That would seem to be bad news for Bill Ackman — FTC inaction is the main reason why his company has lost $500 million on his Herbalife bet.

It would also seem to be bad news for the people Ackman claims are being unfairly targeted by Herbalife. Ackman’s Robin Hood presentation last week pointed to data and Herbalife ads showing that the company targets "vulnerable, low income" Latino and African-American communities, and that 95 percent of those who agree to join Herbalife will earn commissions of only $8 per week before expenses.

A timely FTC investigation into Herbalife could change that. But, Keep warns, "We’re in the beginning of the process." A year is nothing to federal regulators, for one thing. And regulators don’t like to be seen as tools of Wall Street.

"Regulators by their nature see themselves as umpires and their role is to keep the game fair and let the talented companies win," Keep says. "Any decision on their part today becomes part of the market dynamic. On the other hand, if there’s oppressive behavior here, it’s the FTC’s job to stop the oppressive behavior."

The short

From Oz’s perspective, "Herbalife's stock price has become somewhat detached from the issue of it being a pyramid scheme or not. The stock price," he says, "has taken on a life of its own, pegged on the theatrics of investors rather than Herbalife's business model."

And the business model is questionable. A blogger at financial site Seeking Alpha recently pointed out that "Herbalife’s stock is running like crazy while the company does things like setting up a plan to pitch against obesity in Cambodia" — a country with an absurdly low obesity rate of one person in every 50.

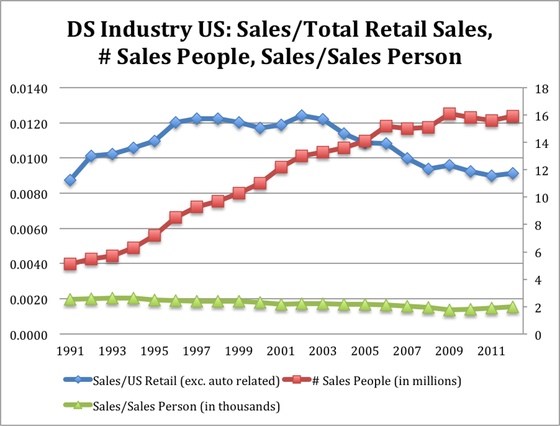

What’s more, the MLM industry’s market share doesn’t seem to be growing at all. In fact it seems to be shrinking. William Keep points to a chart he recently published:

According to numbers released by the Direct Selling Association, the number of MLM salespeople increased from 5 million to 15 million in the last 20 years while sales as a percentage of total US retail sales declined. This means that 15 million MLM salespeople now generate the same percent of total US retail sales that 5 million did 20 years ago. "Their customer base is ephemeral," Keep says.

Wall Street seems to be turning a blind eye to the pyramid-scheme discussion

How that — and / or the FTC’s eventual action or inaction — will affect Ackman’s bet and Herbalife’s continued existence is yet to be seen. But Keep has an explanation for why Wall Street seems to be turning a blind eye to the pyramid-scheme discussion.

"Ackman’s gotta be right that regulators will act and that they will be successful in shutting Herbalife down," he says. "Investors only need to be right in one thing: that none of that will happen any time soon."

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/14541171/herbalife-lead.1419980122.jpg)