As with his art, Prince’s presence within the music industry was a mix of solid genius and commendable folly.

The Minneapolis artist signed to Warner Bros Records aged 17 and subsequently wrote, produced and played every instrument on his debut album, 1978’s For You. In doing so, he set out his stall early; here was a musical prodigy who did everything on his own terms and would kowtow to no one. Warner had immense faith and stuck with him through six years and six albums until he scored his first No 1 album, 1984’s Purple Rain. That faith was repaid by years of phenomenal sales, but eventually resulted in one of the most spectacular artist/label fallings-out in history.

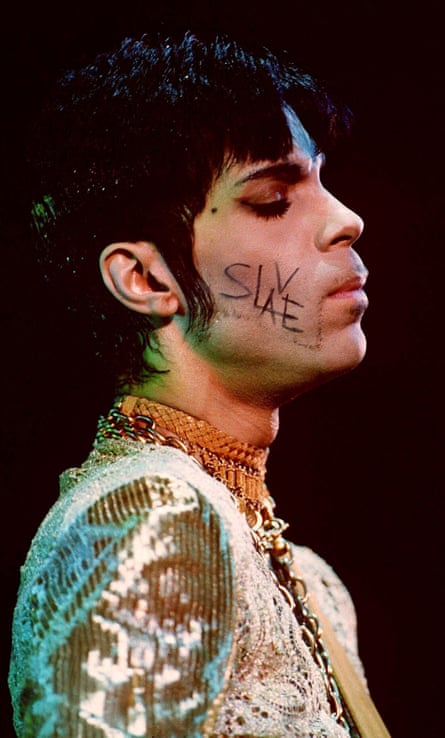

In 1993, Prince went to war with Warner, accusing the record company of commercial and artistic indenture, subsequently appearing in public with the word “Slave” written on his face and changing his name to an unpronounceable symbol. In August 2015, when speaking about the artist-owned Tidal streaming service he was licensing his catalogue to while pulling it from everywhere else, he revived this accusation. “Record contracts are just like – I’m gonna say the word – slavery,” he was reported as saying. “I would tell any young artist … don’t sign.”

The period from 1995 to 2014 had seen him ping-pong through the major label system, signing short-term deals for different albums with EMI, Arista, Columbia and Universal before eventually returning to Warner. Throughout that time he remained utterly sovereign, pursuing his own agenda even if it was at odds with what the label wanted.

Arguably the most extreme example of that was his decision to give away his latest album, Planet Earth, as a cover mount on the Mail on Sunday in July 2007, to coincide with his run of 21 shows at the newly opened O2 in London. He was contracted to Columbia at the time and hadn’t told them about the deal, resulting in the label refusing to release the album in the UK. Not that Prince cared. Perhaps more than any other artist in recorded music history, Prince was wonderfully and idiosyncratically insubordinate when it came to the intricacies of artist-label politics.

What was to prove his biggest feud was not with a corporation, however, but the internet as a whole. Just like his dealings with assorted labels, his relationship with the online industry was spiky. He was certainly willing to experiment with the internet as both a distribution and commercial channel: he initially released 1998’s Crystal Ball online; he set up the NPG Music Club in the early 2000s, a time when hosting music online was affiliated with piracy, and by 2009 he had set up the $77-a-year Lotusflow3r subscription service, a platform for his multi-album release. The rest was far from straightforward.

His biggest career disputes stemmed from instances in which he believed the internet did not align with his terms. In 2007 came the “dancing baby” copyright case, in which a family who had uploaded to YouTube a clip of their infant dancing to Let’s Go Crazy found themselves at the sharp end of a legal assault. Prince said he wanted to “reclaim his art on the internet” and went about wiping as much music as possible from the video site. That was just a foreshadowing of what was to come; he also had eBay, the Pirate Bay, Vine and various other sites in his crosshairs in the following years.

In 2010, Prince boldly declared: “The internet is completely over.” He was to eventually clarify this point five years later in an interview with the Guardian. “What I meant was that the internet was over for anyone who wants to get paid, and I was right about that,” he said. “Tell me a musician who’s got rich off digital sales. Apple’s doing pretty good though, right?”

He would go on to to revise his position on digital music by giving Tidal the exclusive on his substantial catalogue (barring the odd blip, such as when his song Stare appeared on Spotify a mere month after he said he had a “non-restrictive” arrangement with its Jay Z-backed rival). YouTube, however, remained his biggest adversary, initially scrubbing his cover of Radiohead’s Creep at Coachella from the site until Thom Yorke, himself no fan of the giants of online music distribution, intervened and asked for it to be reinstated.

While Prince’s views attracted many accusations that he was a contrarian and a luddite, they seem prescient in 2016. The global record industry trade body IFPI used much of its recent report to bemoan what it termed the “value gap” in terms of label income. This was caused by services such as YouTube, where an estimated 900m users generated just $643m (£448m) in royalties, compared to the 68m paying subscribers to services including Spotify and Apple Music, who generated $2bn. As with his music, Prince would strike out alone, then watch on as other artists started to catch up with him.

His self-governing attitude within an industry based on compromise and consensus is perhaps best illustrated through Paisley Park. Much like Graceland, Abbey Road and Hitsville USA, this was Prince’s true fiefdom, where he could create music entirely on his own terms and develop the musicians and performers he believed best reached his exacting standards. Unlike Charles Foster Kane’s Xanadu, this was not a walled palace in which to hide from the world; this was a place where he was able to keep making music. It became ever more important and symbolic of his demand for autonomy as the record business, in freefall since 2000, played safer and safer.

As a musician, Prince was fearlessly alone – a self-propelling catalyst with a vision so powerful it will take us decades to truly understand it. Yet unlike others who can be classed in the same artistic league – Bob Dylan, David Bowie, Joni Mitchell to name just three – he applied the same logic to the business that inconveniently sat between him and his fans. Prince proved that the industry can be bent to your will and not the other way around.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion