A cartoon journey through a Middle East childhood

- Published

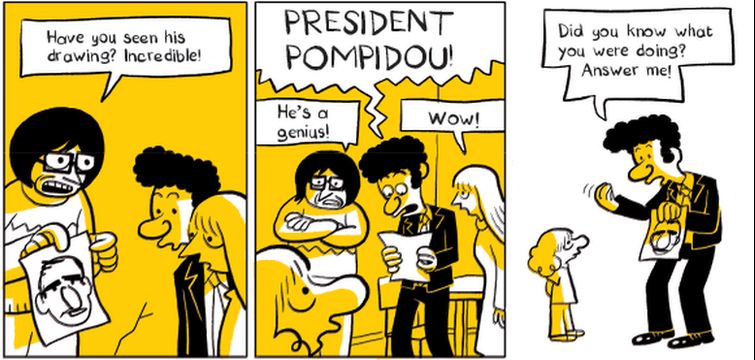

It all began with a portrait of Georges Pompidou when he was a small boy, says French-Syrian cartoonist Riad Sattouf, explaining a career which is now bringing him to international attention.

"When I did that drawing I saw in the eyes of my grandmother that I was exceptional and then after that I tried again and again to find this in the look of other people. And this is what I'm still trying to do today," Sattouf says.

Sattouf's own life hadn't featured prominently in his work until now but he says the impetus for his recent highly acclaimed book, The Arab of the Future - a memoir of his childhood in the 70s and 80s - came from the beginnings of Syria's civil war.

From Paris, he began trying to get some of his Syrian relatives out of Homs in 2011 when fighting in the city, dubbed the "cradle of the revolution", was just beginning to break out. "I was convinced that the country would go to complete destruction," Sattouf says.

However, it proved more difficult than he anticipated to get permission from French authorities to relocate them.

"I wanted to tell in my comics what was happening in the French administration," he says, adding that he wanted "a sort of funny revenge" on the bureaucrats.

In the first volume of Arab of the Future, recently released in an English translation, he tells of how his Syrian academic father Abdelrazak met his French mother Clementine.

Afterwards Abdelrazak rejected a teaching post at Oxford University in favour of one at a university in Col Gaddafi's Libya, before moving on to Syria under Hafez al-Assad. His wife and the infant Riad went with him.

Through it all Abdelrazak holds forth to his long-suffering family - and to us - on the need for Arab countries to be "forced" to be modern. He expresses a sometimes grudging admiration for both Gaddafi and Assad.

In the book, each country is depicted by a particular colour - Libya is yellow like its sun and sand, France is the blue of the sea near his grandmother's Brittany home and Syria is red like its soil.

Sattouf says he chose the technique to convey the sharp dislocation he felt as a child when moving between these different places. "If you stay one hour under a red light, and you go out, the world will seem green," he explains.

Sattouf says he drew entirely from memory and the book is full of the impressionistic, sometimes visceral nature of childhood recollections, such as one memory from a ration queue in Libya.

Childhood and adolescence are themes that recur in Sattouf's work. In La Vie Secrete des Jeunes (The Secret Life of Young People), a strip that appeared in the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo between 2004 and 2014, he depicted conversations overheard between teenagers and young people in various places around Paris.

Sattouf started working for the magazine after being personally invited to do so by the cartoonist Cabu, one of those killed in the January 2015 attack by Islamist extremists on the magazine's offices.

By that time Sattouf had stopped producing the strip but in the first issue after the shootings he contributed a one-off return to the series.

It depicted a man of North African origin whom Sattouf saw in his street the day after the attacks. He is discussing the attacks on his phone and appears to be arguing with someone who suggests the assault were part of a unspecified "plot" before saying: "I don't give a **** about Charlie Hebdau... But if you don't like it, don't read it, you don't kill them".

While Sattouf insists he is not a satirist, in The Arab of the Future, politics inevitably looms threateningly at the edges of his portrayals of his family's experience, particularly in Hafez al-Assad's Syria.

The first word he learns in Arabic is "yahudi" or "Jew", which some children in his father's village accuse of him of being on account of his blond hair and foreign mother.

Some critics have pointed to scenes such as this as proof that the book's portrayal of the Arab world is reductive and misleading, but Sattouf rejects this.

"The children I met in Syria,... they were educated to hate Jews and to hate Israel but they were extremely intelligent people. They had nothing and they were very clever."

And indeed, Sattouf points out that that in some ways the cultural gap between France and Syria was not as great as one might expect.

"For example my two grandmothers were living in a very different way but their lives were also similar in many ways, the ways they raised their children, [the fact that] the men had the power. There were the same moral values. The differences were economic of course, Syria was... poor and they were living in bad conditions."

This point is driven home when he evokes the memory of the hut-like dwelling of his grandmother's neighbour, Bebette.

And then there is his mother Clementine, who despite being a highly educated Western woman, stoically accepts Abdelrazak moving the family to one trying situation after another. The only time we really see her snap is in a row with Abdelrazak at the end of volume 2 over an honour killing in his family.

"I think she was like a lot of women of her generation, because not all of them were independent," Sattouf says. "She was a housewife, raising her children and waiting for her husband to become somebody important to have a better life."

Indeed, what comes across most strongly from the books is perhaps not so much the differences between one place and another, but how all of them have changed over time.

In one sequence, the family walk around Leptis Magna, one of Libya's famed Roman archaeological sites which experts fear may yet fall victim to the country's sprawling set of conflicts.

It's a cue for Abdelrazak to have a laugh at the Romans' expense: "They thought they were the strongest people in the world! And look now, it's ruins! Ha ha!"

A bitter echo, perhaps, of how the latter-day projects of Gaddafi and the Assads have turned out.

- Published1 March 2016

- Published13 January 2016