Is it 'ludicrous' to ban climbers from Uluru?

- Published

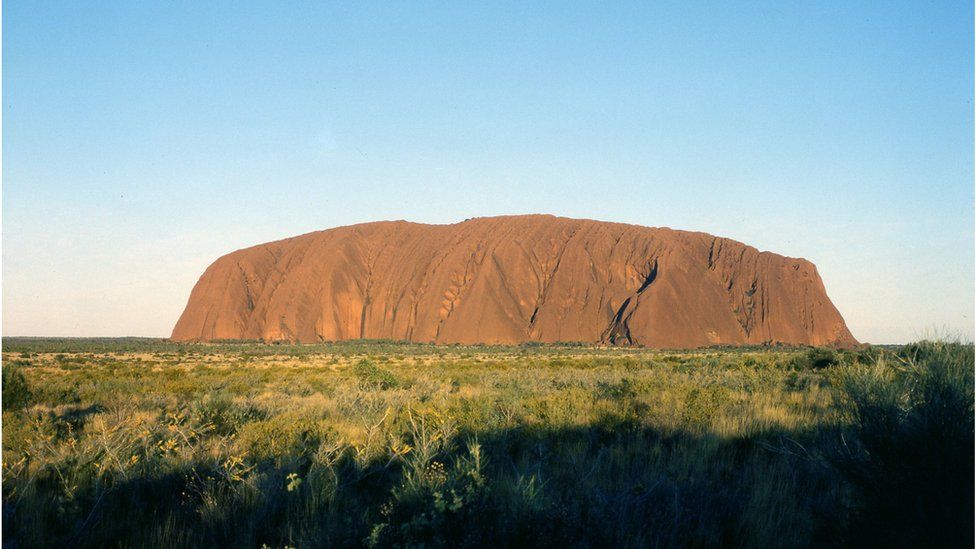

The prominent sign in seven languages at the base of Uluru, the giant red monolith in Australia's dusty red heart, could hardly be clearer.

"Uluru is sacred in our culture," state its Aboriginal owners. "It is a place of great knowledge. Under our traditional law climbing is not permitted. Please don't climb."

While thousands of tourists disregard the sign and scale the World Heritage-listed rock every year, their numbers are dwindling.

Under a plan announced in 2010, once fewer than 20% of visitors venture up the steep path, which has claimed at least 35 lives since the 1950s, climbing will be officially banned.

Not everyone, though, supports the move, with some tourism operators warning it will deter people from visiting the national park containing Uluru, formerly known as Ayers Rock, and Kata Tjuta, or the Olgas - another massive rocky outcrop.

Now the Northern Territory's chief minister, Adam Giles, has stirred the pot, comparing the rock to the Eiffel Tower and Sydney Harbour Bridge - both routinely scaled by visitors - and dismissing a ban as "ludicrous".

"We should explore the idea of creating a climb with stringent safety conditions and rules enforcing spiritual respect," Mr Giles, who is Aboriginal, told the Territory's parliament. That would bring "significant economic benefits" to indigenous locals, he said.

'Snail trail'

His remarks unleashed a storm of criticism, with Francis Kelly, chairman of the Central Land Council, which represents the area's traditional owners, calling them "completely wrong" and "offensive".

"Uluru is for everyone in the world to enjoy, but we are the caretakers," says Leroy Lester, whose father, Yami, a celebrated land rights activist, officiated at the ceremony where Uluru was handed back to its Aboriginal owners in 1985.

Mr Lester told the BBC: "The climb is dangerous and the people going up there leave a snail trail (of erosion marks) on the rock. It also goes against the spiritual beliefs of the oldest living culture on the planet."

A tourism draw since the mid-20th Century, Ayers Rock gained international notoriety in 1980, when Azaria Chamberlain disappeared from an adjacent campsite. Her mother Lindy was found guilty of murdering her, but the conviction was overturned in 1988 and in 2012 a coroner ruled that a dingo took the baby.

After regaining ownership of Uluru - a move bitterly opposed by the Northern Territory, which had previously controlled it - Aboriginal elders leased it to the federal government for 99 years, with the land to be jointly managed by them and the national parks service.

Although traditional owners receive a portion of the entry fees, hopes that jobs would be created for locals in the park and at the resort in nearby Yulara have largely been dashed. The Aboriginal community of Mutitjulu, at the foot of the rock, is one of Australia's poorest.

The sight of tourists climbing Uluru - the site of an important ancestral story - rubs salt in the wound. "This is a very special place to us and we want to protect it for the next generation, and the generation after," says Alison Hunt, an elder and former member of the board which manages the park.

She adds: "The chief minister should consult the custodians of the land before issuing his public statements. We're getting tired of people making a political issue out of this."

Rock revenue

With the Northern Territory still enviously eyeing Uluru, some suspect Mr Giles of a hidden agenda. He told parliament that the question of whether the rock should be climbed was "a decision for Territorians, not bureaucrats in Canberra".

The chief minister recently visited Uluru with the Australian golfing legend Greg Norman, who wants to open a golf course at Yulara. That idea is anathema to Mr Lester. "The place is going the way of a theme park," he says. "It seems to be all about making money these days."

Last year, an opponent of climbing on the rock - which the parks service already bans when it is too wet, windy or hot - cut the safety chain which runs along the ascent.

Earlier in the year, a Taiwanese tourist had to be airlifted off Uluru after falling 20m into a crevice and suffering head injuries, earlier in the year.

Aboriginal people are keen to develop small-scale tourism ventures which could offer an alternative to the climb. "Visitors can sit down with us around a campfire and learn about the rock and our culture, hear the stories and history of ourselves and the land," says Ms Hunt.

"They should do more than just race in, climb the rock, go back to the resort and then fly out," says Donald Fraser, a former chairman of the board of management.

Local people, Mr Fraser adds, "only get a bit of money from the (park) gate... It's like we've got a hole in the pocket instead of money going into the bank."

- Published26 October 2015

- Published22 April 2014

- Published12 June 2015