“I lifted up my T-shirt to check on what I thought had just been a small heat rash,” writes BuzzFeed correspondent Ali Watkins. “It had shown up along the right of my back, extending out from a handful of mosquito bites I had picked up… it had seemed relatively tame [but] now, it was inching across the front of my stomach and down my legs... Meanwhile, my right eye was inflamed and bright red, almost akin to a busted blood vessel.”

Watkins is describing the symptoms of a Zika virus infection that she contracted on a recent trip to Mexico. For many people, infection with this mosquito-borne virus causes an illness with symptoms just like those experienced by Watkins: fever, skin rash, joint pain and conjunctivitis. For others, these symptoms are so mild that they go completely unnoticed.

For pregnant women, however, infection with Zika virus is linked to a severe birth defect called microcephaly, which results in an abnormally small head and brain. Research published today in the journal Nature provides the first direct evidence that Zika virus does indeed cause microcephaly; several other recent studies explain why the developing brain is particularly susceptible to infection, and describe the cellular and molecular events that link infection to this defect.

During the earliest stages of foetal development, the nervous system consists of a hollow tube running along the back of the growing embryo. The inner lining of this neural tube is packed with cells radial glia, which have fine processes spanning the thickness of the tube. The radial glia act as stem cells, dividing to produce immature nerve cells which climb onto their mother cell’s radially aligned fibre and then crawl along it, with amoeba-like movements, towards the tube’s outer surface.

Nerve cells are produced in vast numbers, and at different rates along the length of the neural tube, eventually forming the brain at one end and the spinal cord at the other. Immature nerve cells migrate outwards in waves, with each successive wave migrating past the one before it, giving rise to the six layers characteristic of the cerebral cortex, which thus form in an ‘inside-out’ manner.

Researchers at the University of California in San Francisco used a sophisticated technique called single-cell RNA sequencing to analyse the genes that are active in different types of cells found in human foetal brain tissue. Their results, published last week in the journal Cell Stem Cell, show that radial glial cells express high levels of AXL, a cell surface receptor that plays an important role in regulating cell growth, proliferation, and survival.

It was already known that Zika virus uses the AXL protein to infect human skin cells, and so it seems likely that the virus uses this same receptor to gain entry into radial glial cells in the developing brain, too. Inside radial glia, AXL is localised to structures called end-feet, which come into contact with blood vessels, and also with the canal at the centre of the neural tube; this will eventually form the brain’s ventricular system, which is filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Thus, once crossing the placenta, Zika virus particles may use the end-feet to enter the developing brain, via either the bloodstream or cerebrospinal fluid.

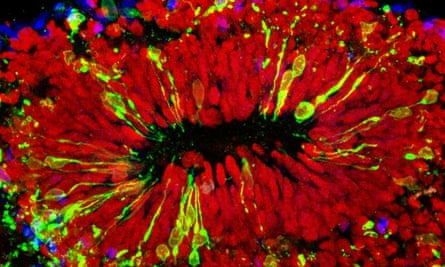

Using cerebral organoids, or lab-grown ‘mini-brains’ derived from stem cells, others have shown that the virus prefers to infect radial glia in the embryonic forebrain, which gives rise to the cerebral cortex. The virus inhibits the growth of these cells, and also kills them off, apparently by activating TLR3, an immune system receptor which triggers programmed cell death. TLR3 activation also perturbs networks of genes involved in neurogenesis (the formation of new nerve cells), the differentiation of newborn cells, and the growth of their fibres.

Researchers at the University of São Paulo in Brazil – the epicenter of the current Zika outbreak – now show for the very first time that the virus causes microcephaly in an experimental animal model. They infected two different strains of pregnant mice with Zika virus isolated from a patient treated in the Brazilian municipality of Belém, and examined the pups immediately after they were born.

They found that the pups of infected mice had far fewer neurons, so that the cellular layers of the cerebral cortex were significantly thinner than those of pups born to uninfected mice – malformations very similar to those seen in human microcephaly. At the cellular level, many of the neurons in the cortices of infected mice also contained large cavities, a characteristic of programmed cell death.

From these studies, it now seems clear that Zika virus causes microcephaly by infecting and depleting radial glia in the developing brain, the population of ‘founder’ cells that normally generate all the different types of nerve cells in the cerebral cortex.

The World Health Organization has declared that Zika virus constitutes a public health emergency of international concern. Cases have now been confirmed in more than 50 countries, and epidemiologists have estimated that more than 2.2 billion people in tropical and subtropical parts of the world are now at risk of infection. Treatments are therefore desperately needed, and cerebral organoids and animal models will undoubtedly help researchers to test their effectiveness.

References

Nowakowski, T. J., et al. (2016). Expression Analysis Highlights AXL as a Candidate Zika Virus Entry Receptor in Neural Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell, 5: 591-596 [Full text]

Dang, J., et al. (2016). Zika Virus Depletes Neural Progenitors in Human Cerebral Organoids through Activation of the Innate Immune Receptor TLR3. Cell Stem Cell, 19: 1-8 [PDF]

Cugola, F. R., et al. (2016). The Brazilian Zika virus strain causes birth defects in experimental models. Nature, DOI: 10.1038/nature18296 [Full text]

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion