Remember when the future of retail was online? Now it seems that online retailers have decided they can’t get by without bricks and mortar.

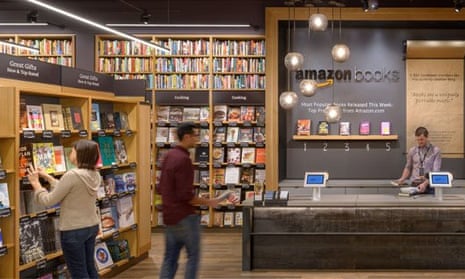

Amazon raised eyebrows in November when it opened its first brick and mortar extension – a bookstore in Seattle’s University Village. The online giant’s rise, after all, is blamed for laying waste to independent bookshops across the country.

But Amazon is only among the latest, if largest, e-commerce players to take a stab at traditional retail after starting life online.

In the last few years, some 20 online companies in the US have launched a physical presence to better market their wares, forge closer customer relations, and yes, boost online traffic and sales. Amazon aside, these include mostly specialty and clothing stores such as Warby Parker, Bonobos, Birchbox and Casper.

The trend also reflects the broader industry imperative around “omni-channel” retailing, where merchants aim to provide customers with a seamless experience whether shopping online via desktop or mobile device or at a traditional retail store.

Underscoring that point, the National Retail Federation’s annual “Big Show” conference in New York earlier this month featured half a dozen sessions that included the term in their titles.

“It’s very hard to launch a brand these days that’s just online-only. It’s an incredibly difficult and crowded e-commerce environment,” said Sucharita Mulpuru, a retail analyst at Forrester Research. She noted there are more than 800,000 online stores, all vying to attract customers through the gateway of Google.

Online real estate has become crowded and expensive. Bidding on keywords against the likes of Amazon and large traditional retailers to land on the first page of search results is a costly game.

Macy’s and Nordstrom, for example, spent an estimated $6.4m and $4m, respectively, in paid search listings for the top 1,000 apparel-related keywords in the first quarter of 2015, according to a study this month from L2 Inc, a research firm that tracks digital brands.

“Clicks disproportionately go to the highest-placed search ads, with little room for differentiation,” states the L2 report, which examines what it calls “evolved retailers” – online merchants that have opened brick and mortar storefronts.

By opening physical stores, they aim to increase awareness and draw customers in a realm where the retail options aren’t infinite or influenced by an all-powerful gatekeeper. And for purveyors of tactile and personal products like clothing, eyewear and jewelry, selling stuff in person has an obvious appeal.

For many, the offline foray has started with a trial pop-up shop before launching flagship stores in high-profile shopping districts like New York’s SoHo neighborhood or Chicago’s Michigan Avenue. Encouraged by the results, some have since expanded quickly.

“The big benefit of the flagship stores is that they’re terrific marketing vehicles,” said Jason Goldberg, senior vice-president of commerce and content at digital agency Razorfish. “Not only do those stores tend to be economically successful on their own but they generate a huge lift in incremental shopping to the online store.”

That’s been the case for Warby Parker, which has created a popular brand by selling stylish eyeglass frames for under $100. After starting online in 2010, it opened its Soho flagship three years later and now has 20 stores nationwide, with plans to add another 20 this year.

Co-founder and co-chief executive Dave Gilboa said Warby Parker stores that have been open at least two years are already profitable. “We also see a halo effect where stores themselves become a great generator of awareness for our brand and drive a lot of traffic to our website, as well and accelerate our e-commerce sales,” he added.

Gilboa declined to disclose actual sales figures but the company’s rapid ascent hasn’t been lost on investors. T Rowe Price last spring led a $100m round of funding in Warby Parker at a reported $1.2bn valuation, making it a so-called unicorn.

While someone can leave a Warby Parker store sporting a new pair of glasses, other e-tailers have opened what are essentially showrooms. This approach allows customers to size and sample products while minimizing real estate and other traditional retail costs.

Among the best-known brands adopting this model is menswear shop Bonobos. Billed as “guideshops”, its 20 stores let customers try on clothing while orders are placed online for home delivery.

The concept is that men want to shop in stores, but don’t necessarily want to leave toting shopping bags. “This supported our idea of using Bonobos.com as the place to fulfill orders, so we didn’t have to worry about stocking inventory in a location and we could focus more on the customer experience,” said Erin Ersenkal, Bonobos’ chief revenue officer.

The average order size in Bonobos’ stores has proven to be twice that of online, with a higher proportion of new customers also coming through the guideshops.

Similarly, jewelry e-tailer Blue Nile last year opened its first standalone outpost in the Roosevelt Field mall on Long Island for similar reasons to Bonobos. “Consumers’ No 1 objection to buying [jewelry] online is not being able to see and touch and feel the product,” explained CEO Harvey Kanter.

Purchases are still made online, where the company says prices are typically 20% to 40% lower than its traditional counterparts.

Unlike others embracing brick and mortar, publicly traded Blue Nile is hardly a startup. Founded in 1999, it survived the dotcom bust, and is on track this year for revenue of about $500m. So why hit the mall now?

Compared with other e-commerce categories, jewelry still has low penetration online, said Kanter. Venturing offline is a way to spur higher growth. Since opening last June, Blue Nile has seen a lift in traffic and sales in the region around its initial Long Island location. As such, it plans to open another three or four “Webrooms” in the first six months of 2016.

As Blue Nile and other e-tailers branch out, though, don’t expect them to pop up on Main Street. Given the focus on marketing, marquee locations in select cities are more likely to be their turf. “Their economic future isn’t tied to opening a store in Montana or Idaho or some of those smaller markets,” said Razorfish’s Goldberg.

Even so, Claude de Jocas, research lead on the L2 study, said the benefits of economies of scale could lead to adding more locations. “Some are also beefing up their physical retail teams with senior-level hires, suggesting aggressive expansion plans are in the works,” she said.

So what about Amazon? Its bookstore is closely linked to its website. Amazon Books’ 5,000 titles are selected based on customer ratings and pre-orders on Amazon.com. Each book is displayed face-out with a barcode to check pricing using its app. The outlet also lets people test drive its devices like the Kindle e-reader and Fire tablets.

Amazon didn’t respond to media inquiries, and has previously declined comment on plans for additional locations. Jennifer Cast, vice-president for Amazon Books, told the Seattle Times in November: “We hope it’s not the only one. But we’ll see.”

Other “evolved” retailers probably hope Amazon doesn’t adapt well to selling on land.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion