Some dude named Shakespeare once wrote: brevity is the soul of tweet. Smart fellow. The 140-character limit is not merely some incidental feature of Twitter; it's the very essence of the service. The mandate to be concise means that Twitter distinguishes itself from abundant conventional blogging platforms. Tweets can be observations, jokes, questions, or carefully distilled ideas, but they cannot be lengthy treatises or complex arguments.

This essential feature is under threat. Re/code is reporting that Twitter is considering removing the 140-character limit and replacing it with a 10,000-character cap. This isn't the first time we've heard such reports; Re/code wrote the same thing in September.

The report suggests that long tweets will be hidden behind some kind of user interaction to expand them, meaning that Twitter timelines will continue to pack in multiple tweets, and we won't be forced to scroll past long essays on the service. This means that the Twitter experience with longer tweets will be similar to the current one.

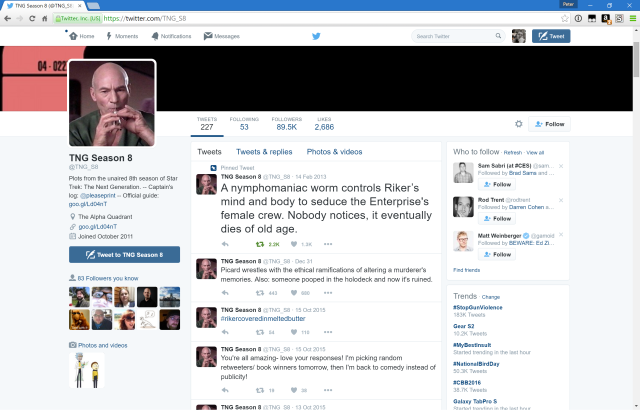

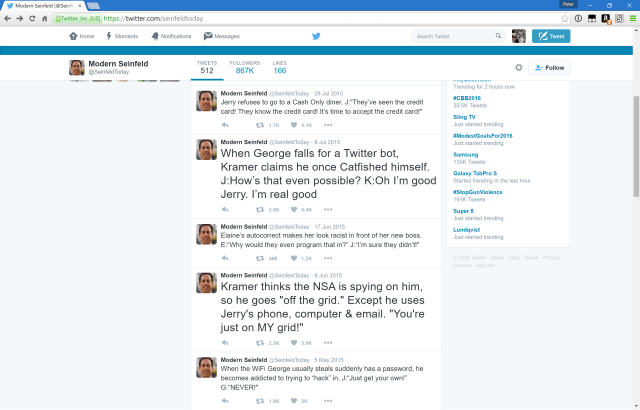

But it won't be identical. The nature of what people write will change. Freed from the editorial constraint that the 140-character limit imposes, Twitter risks losing both the quickfire off-the-cuff gems, the ones banged out almost stream-of-consciousness style during the latest presidential debate or award ceremony, and the carefully considered, elaborately crafted tweets that use every one of the 140 characters for meaning and purpose. Twitter wants to change the very thing that makes Twitter great, because Twitter is trying to figure out how to make money with the beloved service. Removing the character limit, however, is a terrible idea.

But we already have places to write long tweets

It also seems thoroughly redundant. For those who really want to write more than 140 characters, there's Twitlonger. If you want Twitlonger with fonts, there's Medium. Of course, these are both third-party services, and as such there's a conceptual barrier between them and Twitter. If you truly want or need more than 140 characters, you have to make a very deliberate decision to use a greater-than-140-character service. This barrier forces a reassessment: do you really need more than 140 characters to express yourself, or are you simply being lazy? As dead French gambler Blaise Pascal wrote, "Je n'ai fait ce tweet plus long que parce que je n'ai pas eu le loisir de le faire plus court.": I made this tweet long because I lacked the leisure to make it shorter.

Twitter is considering such a destructive move not because of the demands of hardcore tweeters—better clients and some kind of limited editability would surely be higher up the wish lists of Twitter's heaviest users—but because of its desire to make Twitter better for all the people who don't use Twitter. The company, or at least the wolves on Wall Street, want Twitter to have more users. They're unhappy that Twitter isn't Facebook.

The issue of course is that Twitter isn't meant to be Facebook. Active tweeting requires a certain combination of narcissism and self-importance, the belief that utterances issued into the void are somehow interesting and worth reading. This is not something that will appeal to everyone—every time we write about Twitter some number of commenters proudly boasts to us that they don't get Twitter in particular or social media in general—but among Twitter's loudmouthed users, it's deeply compelling. Twitter gives us the same opportunity as the megaphone and soap box so beloved of the street preacher, without attracting the same moralizing disapproval. Shouting at everybody and nobody from a street corner means that you have a screw loose; doing the same on Twitter simply means that you're living in the twenty-first century. It's a socially acceptable outlet for the same instinct.

A move to long tweets also betrays certain classes of Twitter user. That 140-character limit comes from Twitter's use of SMS messaging: SMS messages are 160 characters long, with Twitter reserving 20 characters for commands and 140 for the messages themselves. To this day, you can use Twitter with little more than a dumbphone and text messages to the company's shortcode. While this archaic system has some annoying features today—for example, you can't start a tweet with a letter 'd' followed by a space, because it tries to send a direct message—it provides a robust fallback at times of duress and civil unrest, when Internet connectivity can be unreliable or non-existent.

This isn't to say that this is Twitter's biggest use case, but direct from-the-scene reporting of civil wars, natural disasters, and other catastrophes has proven to be one of Twitter's most valuable strengths; cutting off or limiting such usage does not feel like a positive step for the platform.

Walled gardens

The company's other motivation is to keep the people who do use Twitter in Twitter, and especially inside the Twitter app. This makes it much more likely that they will see an advertisement or interact with a promoted tweet. With longer tweets, news publications will—if they're crazy—be able to put entire articles directly into Twitter. Their readers will never even need to leave the site. This is again an attempt to make Twitter into Facebook, because Facebook is already doing the same.

Again, though, it does little to serve Twitter users. Twitter users seem happy to use Twitter as a springboard to content from all around the Web. Being trapped within Twitter does them no favors. It is a change that only makes sense to Twitter's shareholders and board.

Twitter, with its steady feed of new interesting things, its unique platform for speaking out, and its interactivity, is already a fine service, one that has value to us because it isn't Facebook. For example, Twitter gives all participants in a discussion a kind of equality. On Facebook, a page's owner can shut down or manipulate any discussion on the page.

Striving for the same kind of audience with the same kind of reach is a mistake. Twitter users want Twitter to be Twitter, and I daresay that many of us would pay for it, and many of us wish it were better at being Twitter. The official Twitter clients, for example, leave a lot to be desired when compared to third-party clients. But they have a privileged position; third-party clients are capped at the number of users they support, to ensure that most Twitter users use Twitter's official clients most of the time, and hence that the advertisements on the site are seen, at least occasionally. It is not beyond the wit of humanity to imagine a system by which third-party clients could remain financially viable while also ensuring a revenue stream for Twitter—some kind of revenue share or subscription system, say—and such a thing would be far better for the hundreds of millions of people on Twitter.

Instead, it seems that we will see a stake driven through its very heart, in the name of making it more popular. RIP.

This article, including all the HTML formatting that our CMS uses, comes in at 8,364 characters. Imagine how much better it would have been as a tweet.

reader comments

141