What Are Those Kids Doing With That Enormous Gun?

The strange photos that showed up on the lost iPhone may not have been exactly what they seemed.

In the summer of 2013 my friend Maura lost her iPhone in the Hamptons. (Maura asked me not to use her last name because of the sensitive nature of this story.) She was partying at a decidedly retrograde bar in Montauk—The Memory Motel. Locally, it’s known as one vertex of the “Bermuda Triangle,” a trio of bars where sobriety and personal dignity tend to go missing under murky circumstances. (The Memory Motel in particular is also famous for inspiring The Rolling Stones’ worst song.)

As Maura left the bar around closing time that Saturday night, she realized her phone had gone missing. She talked to bouncers and bartenders who professed ignorance, then had a friend call her phone, which went directly to voicemail. She’d gone out that night with the battery fully charged, which suggested that someone had found the phone and turned it off. When Maura got to her computer later that night, she went to her iCloud account and selected Find My iPhone. Since the phone was off, she wasn’t able to bring up a GPS-generated map of its location. But she checked the “notify me when found” box so she’d receive an email when her phone connected to the Internet again. She also put the phone in “Lost Mode,” which meant her phone display would flash a number where she could be reached so a sympathetic party could get in touch to return it.

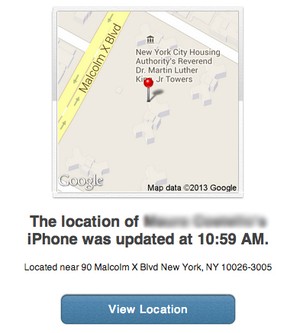

Sunday passed without any further information and Maura returned to Manhattan. But on Monday morning, she received a message from Find My iPhone. The device had been located: It was currently in Harlem, at the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Towers, a housing project several blocks north of Central Park. She had no idea how her phone had made the 120-mile trek from Montauk to Manhattan, but she had a surreal vision of it traveling on its own, facing the same choices any yuppie would face: Do you catch a ride in someone’s car? Take the LIE? Or is it faster to hop on the Long Island Rail Road?

As soon as she received the email that Monday morning, Maura called her iPhone from her work phone. It rang once and then immediately went to voicemail. When she tried a second time, the phone was off again. She didn’t quite have a plan, she told me. If the GPS map had shown a more precise location—an exact apartment instead of a pin in the middle of a housing project—she would have asked the police to check it out. But since she had no idea who actually had the phone, she thought she might just call that person up and ask for it back.

But the phone stayed off for the next two weeks. She gave up hope of recovering it and switched to an old flip phone for a while. Soon afterwards, she moved to Canada, got another smartphone, and started a new job. The whole matter drifted almost entirely from her mind.

Then, in August, she got another email. Find My iPhone had located the device again: It was in Sana’a, Yemen. That’s when the pictures began appearing in her iCloud account.

The stolen phone that gives access into another life: It’s a new mode of storytelling for our technological age, and it is only becoming more common. Around the same time Maura lost her phone, Matt Stopera, a staff writer for BuzzFeed, lost his in an East Village Bar; he ended up following it to China, where he became a minor celebrity. Maura’s experience started in a similar way: When the pictures started showing up, she realized that she was linked to a Yemeni family in a way that would have been inconceivable a decade ago.

Here’s the first one that caught my eye: an adorable kid in a purple plaid shirt, maybe a little over 2 years old, with his knock-off Nikes velcroed onto the wrong feet. (Note: We’ve blurred the faces throughout this story to protect the identities of these Yemeni strangers.) He looks up warmly at the camera, perhaps smiling at the person who slicked his hair into a toddler side-part—a hipster ’do that would have worked perfectly in Montauk, except the boy is standing in what appears to be a blown-out bunker, with rubble and wood strewn across the ground, a cinderblock wall in the background, and a dented 55-gallon metal drum lying behind him in the debris.

Next picture: an exterior shot of five buildings—a compound, really—clustered dramatically at the edge of a rocky promontory. The structures are built right up to the point where the rock sheers away into canyon. The image quality is blurry and it seems the camera has been zoomed in all the way, the picture taken from even higher elevation. The boxy stone and brick buildings are constructed in what I soon came to recognize as a standard Yemeni architectural style.

Now a picture of a man, probably around 30, dressed in a robe and head wrap and lounging on a mattress. He leans against a bare wall with a satisfied look on his face, his right cheek domed out, stuffed. He is frozen in the act of dipping his hand into a pile of qat leaves, which, when chewed, produce “effects similar to cocaine and methamphetamine”—this per the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, which classifies one of its active chemicals, cathinone, as a Schedule I drug, same as heroin. Despite the DEA’s warnings, qat-chewing is a fundamental act of male bonding in Yemen, as it has been for thousands of years. People throughout the Arab Peninsula and the Horn of Africa generally see qat as a harmless plant that produces a buzzy caffeine-like sensation.

The next picture has no human figures: It is a row of seventeen Kalashnikov assault rifles.

Now more pictures of cute kids, two boys and a girl, all under 10. They are playing with an assault rifle, hoisting it over their shoulders, cradling it. One boy of about 3 stares at the weapon with unguarded admiration, has his hand on the stock. A stoic teenager appears in this series as well, resting on his haunches and holding the rifle by its muzzle like a walking stick, crouched with the weary air of a boy soldier returned home from the front.

More than 300 pictures like these uploaded automatically to Maura’s iCloud once the missing phone came back online in Yemen. There were landscape shots, selfies, Internet memes, pictures of dinner, portraits of military and political figures (Syria’s murderous tyrant Bashar al-Assad and a pre-execution Saddam Hussein both made an appearance), and scores of photos of what appeared to be one extended family. Many of the pictures consisted of cryptic images taken from the Internet and overlaid with lines of Arabic text.

When the pictures of the assault rifles showed up, Maura’s family contacted the FBI.

When Maura first showed me the pictures from her iCloud during a visit to Toronto, my ignorance regarding Yemen was complete. Like most Americans, I knew nothing about the country’s culture, politics, economy, geography, language, religion, or demographics. As a basic remedy, I set up a Google Alert for the word “Yemen”—an admittedly limited way to discover a country, but I wanted to set up a general knowledge slow-drip while I did some background reading. Over the course of nine months, Google delivered hundreds of articles from news sources around the world—the New York Times, Al Jazeera, BBC News, Yemen Times—sketching a rough outline of the country in the process: “al-Qaeda hotbed,” “poorest country in the Middle East,” and “terrorist staging grounds” were among the most common topics.

These news stories reported that United States had labeled Yemen’s al-Qaeda affiliate the most dangerous branch in the world and was touting President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi and the Yemeni government as essential allies in the fight against terrorism. But Yemen’s political leadership was facing its own internal challenges: a secessionist movement in the south (the country had been unified only in 1990, after 23 preceding years as two separate nations), a conflict with Houthi rebels in the north, a severe water shortage, frequent blackouts, and a citizenry where more than half the population lived below the poverty line. UNICEF reported that children in Yemen had one of the highest malnutrition rates on the planet. The World Economic Forum in Geneva ranked Yemen dead last on its Global Gender Gap Index. And the Sydney-based Institute for Economics and Peace placed Yemen 8th out of 162 countries on its 2014 Global Terrorism Index. This was the current state of affairs in Yemen as seen through the lens of Google Alerts.

In the meantime, new batches of photos had uploaded to Maura’s iCloud, which was now linked to her new phone as well as her old one. She noticed her rarely used Skype account suddenly filling with unknown Middle Eastern contacts.

One afternoon, as she planned a trip to IKEA, Maura opened her Notes app to jot down the names of Swedish furniture—Ektorp, Kivik, Malm—only to find the notepad already filled with Arabic writing. At this point Maura began to wonder what information of hers might be exposed to the Yemeni user, so she called the Apple help line. The tech-support representative explained that someone had installed a new operating system without deactivating the old one or unlinking the phone from her iCloud. But there was nothing to worry about, the rep told her; it was amateur-hour stuff, dumb thieves who couldn’t see anything of hers. Maura was looking through a one-way mirror.

As we puzzled through the specifics of what had happened, Maura and I became more and more tantalized by this glimpse into a parallel existence. It was voyeurism at its most basic—simultaneously thrilling and frightening—and like any glimpsed behavior, it was lacking all relevant context. I contacted an Arabic scholar I had known for many years and asked her to translate the writing in the Notes app and on the pictures. Maura sought out information about the guns. A family friend identified the weapon the kids were playing with in the pictures: “Definitely a Heckler & Koch HK33,” the man wrote, referring to a military-grade automatic rifle capable of firing 750 rounds per minute.

I checked the pictures again. The rifle was equipped with a flash suppressor, which allows the shooter to fire the weapon in darkness.

Recently I met with Ali Sultan, a 26-year-old Yemeni stand-up comedian living in Minneapolis, where I live as well. I wanted to discuss the pictures with a cultural native, to get his opinion on what story they told. Sultan, who was born in the capital city of Sana’a, is a rising figure in Minneapolis’ comedy scene. In 2013, he won two citywide stand-up competitions and scored a set at the renowned Gotham Comedy Club in Manhattan, where he performed alongside The Daily Show’s Aasif Mandvi. Onstage, Sultan is relaxed and engaging, despite having arrived in the States 10 years ago with no English (he claims his first word was “always,” picked up from the constantly looping maxi pad commercials that run during daytime television)—and despite the fact that stand-up comedy as a concept doesn’t exist in Yemen. “It’s a strange idea to explain to people back home,” he told me. “So you stand up and then you tell jokes—okay, so you’re a clown? You’re in theater?”

Sultan’s comedy often excavates the casual racism that he and others from the Middle East encounter daily in the U.S., but where another comic might indulge in righteous anger, Sultan works in a wryly amused mode, his genial and vulpine grin underscoring a wicked intelligence. Jokes from his set often begin in racially charged territory and then veer unpredictably. One bit has him working at a gas station (“Living the Arab dream,” he says, fist-pumping mildly) when a black customer confronts him over the just-announced death of Osama bin Laden. Rather than dwelling in this fraught territory, the joke swerves into that great preoccupation of young men everywhere: food, or the lack thereof. This, Sultan muses, as the answer begins to dawn on him, might explain why he and his roommate Osama can never get pizza delivered to their apartment, unit 9-11.

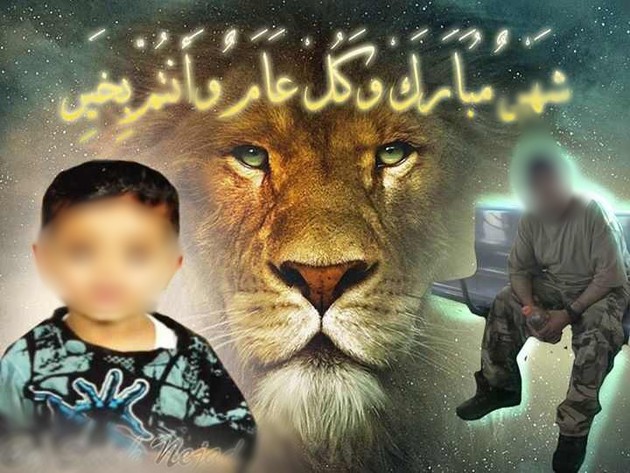

On the steps of the Acme Comedy Club, where he performs regularly, Sultan talked me through the pictures. An October wind curled around us as we examined one of the more peculiar images that had appeared in Maura’s iCloud. When Sultan saw the picture he started laughing.

“Okay, you see a lion in the center—a sign of aggression—and a guy over here with a very serious look, and he’s in camouflage and soldiers’ boots.” Sultan looked up at me. “You know what it says here? ‘Good holiday to y’all, and may you be blessed.’ It’s a homemade card for the end of Ramadan, going to Eid. It’s totally innocent, but Yemenis can be so ridiculous with the Photoshop. This guy in the camouflage is thinking: I’m the coolest, I just learned how to use Photoshop—I’ll put a fucking lion in the middle!”

We moved to another picture that had raised our eyebrows—one of Saddam Hussein. The image had been doctored to look like a still from the game show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? with four multiple choice options along the bottom. The Arabic, Sultan explained, asked how much you loved—or didn’t love—Saddam. It was unclear from the image which answer the phone’s owner would have chosen.

Next came images of moody desert landscapes with captions that turned out to be pieces of advice, aphorisms, proverbs. “The pain of a heart is not healed by apologies,” read one line. “Don’t partner with a jealous man,” read another. A picture of a man in a white thawb—the ankle-length robe common in the Arab world—had a caption reading “Your worthiness is infinite; it is at the center of my heart.” The man was making the “hand-heart” gesture popularized by Taylor Swift and Justin Bieber.

Many images were politically charged: pictures of the Yemeni flag—tripartite red, white, and black—and pictures of the same flag reimagined as a heart. (There were lots of hearts.) There were shots of the Yemeni army looking dignified—standing at parade rest, or leaping into battle, or kneeling in the sajdah position of Islamic prayer. All of these pictures were set against a backdrop of red, white, and black, the Yemeni equivalent of plastering American flags and “God Bless Our Troops” bumper stickers everywhere. There were a number of pictures of President Hadi—America’s main ally in the drone war against al-Qaeda—looking thoughtful and decisive.

The most striking political pictures involved Ali Abdullah Saleh, the former president of Yemen, ousted in 2012 in the wake of the Arab Spring. Someone had Photoshopped him into a series of fervid cinematic tableaux: Saleh with a superimposed black stallion galloping along a rocky coastline; Saleh being hugged by a benevolent leopard; Saleh floating beatific over a field framed by a rainbow.

Sultan and I continued to scroll through the pictures. Finally we came to a picture of a blue-eyed Siberian husky sitting forlornly at a computer, his paws up on the keyboard and an Arabic word bubble coming from his mouth. Sultan translated the text as: “Why won’t she open her messages?”

He paused for a second, then added: “The dog is at an online dating site.”

After carefully studying the photos in Maura’s iCloud, here’s what we pieced together:

After July 15th, when the iPhone pulsed briefly in the Harlem housing project, it went dark until July 28th. Somewhere in this time span, a man named Mohammad—according to his Skype profile—acquired the phone, kept it offline, and filled it with selfies from various spots around New York City. Here is Mohammad dressed in a Bulls jersey and a flat-brimmed Rams cap, working at the counter of a corner bodega, the shelving behind him a dense Dutch still life of cough syrup, cigarillos, condoms, and cat food.

Here is Mohammad riding an open-roofed tourist bus with the New York City skyline as backdrop. Here is Mohammad in an army surplus store trying on a WWI doughboy helmet. Here is Mohammad in the bathroom, shirtless, having just edged up his hairline and trimmed his facial hair, now sporting a tight chinstrap beard and a thin sculpted mustache. Perhaps it goes without saying that it is Mohammad’s face that was Photoshopped into the arrestingly leonine Eid holiday card—a card he appeared to be sending to his young son back in Yemen.

There are Mohammad selfies with sunglasses and without, Mohammad selfies with hat cocked back to the left and to the right. His signature look involves an NFL or NBA replica jersey, but one picture has him in the iconic “I Heart NY” sweatshirt, and another has him wearing a polo shirt with Yemeni bands of red, white, and black. My favorite is a selfie from the drycleaners: He is waiting in line to pick up his newly pressed garments when he notices the full-length wall mirror beside him. Purple track jacket, gray sweats—click.

Then, on August 2nd, the first picture from Yemen appears: a teenager in a white thawb reclining on a couch. Tucked under the boy’s woven gold belt is a large jambiya, a curved ceremonial dagger with an ornately decorated hilt and sheath, a symbol of Yemeni manhood. The boy is smiling and sporting a bright red Air Jordan vest over his Yemeni clothing, a picture so perfect—Nike America meets traditional Yemen—that I would have called bullshit had I not seen it with my own eyes.

At first it is unclear how the phone has made its way to Yemen, but then, in a picture dated August 5th, there he is: Mohammad himself, resting on a mattress in Yemeni clothing. He dips into a large pile of qat leaves, looking relaxed.

Here in his leisure is where Mohammad leaves us. By August 10th, he seems to have given the iPhone to a teenage relative who updates the device under the name “Yacoub”—this is the stoic teen posing with the HK33 assault rifle. Yacoub has flyaway ears that he hasn’t grown into yet, a wisp of mustache over his lip, and constellations of acne decorating his forehead, cheeks, and chin. I’d put him at 15. He rarely smiles but doesn’t look unhappy—you can see him carefully poised on the cusp of adulthood, aiming for some mature stillness.

Here is Yacoub outside Sana’a, visiting relatives and snapping pictures of his younger cousins. He gets a portrait of an adorable little girl, then catches her kissing her younger brother on the cheek. Yacoub and the kids pass the phone around, producing pictures with tilted joyous energy: various permutations of hugging relatives, arms slung around shoulders, scenes of easy rapport—and Yacoub, trying his best to look serious while everyone else is smiling.

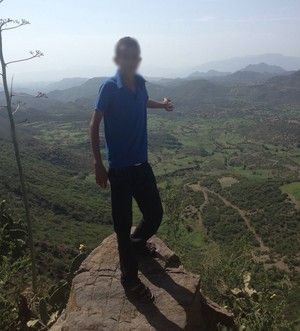

Flipping through these pictures is like watching Yacoub muddle through adolescence in time-lapse. He is deep into the age of identity-building, trying to document and establish his place in the world. He travels through the countryside taking landscape shots: stunning mountains with verdant terraced fields, clusters of houses that stair-step down toward a valley floor. Now he is at a construction site looking supercool behind the wheel of a forklift.

Another picture has him posing before a shuttered storefront with an AK-47 (the safety is on and the gun’s stock is folded under so he can’t touch the trigger). In late August Yacoub writes the Shahada—the standard Muslim declaration of faith—in the phone’s Notes app, where Maura discovers it while making her IKEA shopping list. There is no god but God, and Mohammed is the messenger of God. He writes cheesy love poetry into the Notes app (How does the heart forget you, the taste of sugar that is lost?), he tries to visit Sex.com, he takes selfies with qat wadded in his cheek, he is every teenager in the history of teenagers.

One of the final batches of photos comes from a wedding. Yacoub is taking pictures of a nervous groom and a wedding party populated with familiar faces from the album. When the wedding party leaves the room, Yacoub mounts the elaborately decorated dais and takes a series of selfies on the wedding throne, his stoicism still carefully maintained, perhaps envisioning himself one day married. He puffs his right cheek full of air, as though pretending to have a mouthful of qat, then releases it. As he watches himself in the screen, he seems to see something pleasing, some intimation of oncoming adulthood maybe, and a sly smile slips across his face over the course of three quick snaps.

When I asked Sultan what he thought of the pictures as a whole, he sighed and dragged on his cigarette. “It’s just like any of the people I know in Yemen,” he finally answered. “This could be my cousin Ahmed. But for the untrained eye—or with what we’ve been trained to see by the media—it’s like: Oh my God, these are fucking terrorists! There’s a baby holding a gun!”

So what about the pictures of guns? These, after all, are what initially raised our pulses. Of the 330 pictures that appeared in Maura’s iCloud, about 325 of them are—to quote the Arabic scholar who looked at them—“noteworthy only in their total banality,” photos of boys watching wrestling with Arabic subtitles, or families surveying their crops, or close-ups of hummus and cucumber that could have been pulled from any American’s Instagram feed.

Then there were the ones that seemed not so banal, like the row of 17 Kalashnikov assault rifles. A closer look at the image reveals it to be swiped from the Internet, not actually taken by Maura’s iPhone. The Kalashnikovs are leaning up against what looks like an American garage door at the end of a paved driveway. It is almost certainly not Yemen; it could be the garage door from my last residence.

The pictures of the HK33 are real. The five photos of Yacoub and his young relatives could be taken as evidence that Yemenis are becoming militarized from a disturbingly young age. But they also remind me of a picture I took years ago while visiting a friend’s house, where I too posed with a bristling array of firearms. My picture was parody, of course, but parody is meaningless without context. My gun picture, circulating randomly on the Internet, would certainly worry some people. YouTube is filled with amateur gun porn like this: Americans of all ages emptying magazines from full-auto Heckler & Koch weaponry, then turning to the camera, spent, sighing through dopamine grins.

It’s undeniable that Yemen has a robust and entrenched gun culture. The Small Arms Survey—an independent research group in Switzerland—ranks Yemen 2nd in the world in terms of gun ownership, with an average of 55 guns for every 100 Yemeni citizens. “If you go out in the country, they’re very into guns,” Sultan told me. In rural areas of Yemen an AK-47 strapped across the chest is a status symbol as much as anything. But no one can do guns better than the U.S.—we are the global leader in gun ownership by a significant margin, averaging 89 firearms for every 100 Americans. The only unmistakable takeaway from these five gun pictures is this: In Yemen, as in America, there are children who have access to heavy firepower.

At the end of September 2013, the pictures stopped coming in. Our access to that world was cut off, our voyeuristic thrill curtailed. Maybe the phone broke, or maybe they got a better operating system overlay.

Other possibilities are more unsettling. During the last year, Yemen has slid rapidly into outright chaos. In September 2014, the Houthi rebels took control of the capital, dissolving the parliament and forcing President Hadi to flee into Saudi Arabia. And now the Houthi takeover has led Yemen into a proxy war. Iran is supporting the Houthi rebels while Saudi Arabia, the United States, and a coalition of Arab nations are supporting the fractured Yemeni government. In March 2015, Saudi Arabia began airstrikes against the Houthi forces in Sana’a. Since then, at least 4,300 people have died—2,000 of them civilians, and 400 of those civilians children.

In June the United Nations declared Yemen a humanitarian emergency of the highest order, reporting that the country was “one step away from famine,” with 13 million Yemenis experiencing food shortages and 9 million with little or no access to water. The al-Qaeda franchise is thriving amidst all of this instability. And now the Islamic State—opposed to all of the major actors involved in Yemen—is reportedly setting up shop in the country.

In other words, Maura’s old phone may have vanished from the iCloud for any number of reasons. Meanwhile, there’s another question we haven’t been able to answer. For several months Maura had access to the rivetingly boring daily routines of a family near Sana’a. So did they have the same access? Did the keyhole work both ways? Apple tech support told her no, but Maura later noticed that one of her new Middle Eastern Skype buddies had changed his profile picture to an image that she had taken—a picture of her boyfriend standing on a rock in Croatia, the Adriatic Sea sweeping flatly behind him. I imagined a man in Yemen skimming through Maura’s photos, stopping suddenly, thinking: Pro pic, no brainer. I pictured Yacoub and his cousins crowded around the iPhone, scrolling through shots from the Hamptons. Did they get a peek inside The Memory Motel? What conclusions about America might they have drawn?

What is clear is that our phones and tablets and cameras—our personal tech—are now the mediators of our reality. We use our devices to present ourselves to the world—either the way we really are, or the way we really want to be—and increasingly we try to interpret the world by peering through these technological keyholes. Sometimes we get a distorted picture. Google Alerts paints one picture of Yemen; candid family photographs paint another. It’s up to us to transcend these binary limitations, to suss out the nuance. The computers won’t do it for us.

There’s one image from Yemen that stays with me more than any other, a photo someone took of Yacoub on August 30, 2013, which means the picture pre-dates the current devastation in the country. The sky is a brilliant blue and he is in rural territory outside Sana’a, high above a valley, tip-toed out to the very limit of a rocky ledge. The day is warm—Yacoub is dressed in a royal-blue polo shirt and dark jeans—and there is just open air behind him, the mountains in the distance dissolving into haze, the valley below a patchwork of lush green, with trails and tree line carving some unknown cursive script into the verdure.

Yacoub faces the camera and sweeps his arm back, a gesture of welcoming, an invitation to enter into the glory of the land.

“Look,” he is saying, “come in. We are here.”