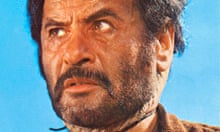

Ennio Morricone was rehearsing his latest concert when news came in that his score for Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight had been nominated for an Oscar. “I was stood in front of a big orchestra, with 90 musicians and 90 people of the choir,” says the 87-year-old maestro. “Everyone started clapping, and then a standing ovation. It was a nice sensation, and also a pleasant surprise because I didn’t expect to be nominated.”

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

It’s not the first time the soundtrack giant has received an Oscars nod: this is his sixth nomination, although he has never previously won. Even his masterpiece for Roland Joffé’s 1986 film The Mission lost out to Herbie Hancock’s jazz arrangements on Round Midnight, something he described to the Guardian as a “theft”.

In 2007, Morricone did receive an Academy honorary award for his “magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the art of film music”, but this seems a relatively meagre reward considering his vast influence: Morricone has composed over 500 scores for cinema, most famously the classic 1960s Italian westerns (spaghetti westerns is a term he apparently finds offensive, so I refrain from using it!) in partnership with Sergio Leone, including The Good, The Bad and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West.

He has also inspired a generation of pop artists working in genres from rock and hip hop to heavy metal and electronica. Jay Z sampled The Ecstasy of Gold from the soundtrack to The Good, the Bad and the Ugly for his Blueprint 2, while bands from Muse to Massive Attack have cited his influence. Metallica take to the stage to his music; the Ramones used to exit to it.

Perhaps it’s Morricone’s refusal to play the Hollywood game that has led to him being passed over: he has spent his entire life based in Rome, has never learned English (today we speak via his translator Gioia) and once turned down the offer of a free Hollywood apartment. “Naturally I would be happy to receive the award,” he says, “but it’s not my main goal. What makes me nervous is that tonight I have a concert, and I would like to do my best. That is the matter of concern, not the Oscar.”

The Hateful Eight marked the first time Morricone had worked with Tarantino on an original score, although the director has often repurposed Morricone’s existing work in his films (Kill Bill: Volume 1 features the main title theme from the 1967 film Death Rides a Horse, for example, while music from 1966’s The Big Gundown, 1973’s Revolver and 1974’s Allonsanfàn all ended up on the soundtrack for Inglourious Basterds). This more direct collaboration was an experience Morricone, who has worked with his fair share of directors and their different demands, describes as “perfect ... because he gave me no cues, no guidelines. I wrote the score without Quentin Tarantino knowing anything about it, then he came to Prague when I recorded it and was very pleased. So the collaboration was based on trust and a great freedom for me.”

This freedom is something Morricone has often been afforded by the directors he has worked with – he once remarked that part of the reason Sergio Leone’s westerns were so slow was that certain scenes were extended in order to accommodate his soundtrack, a luxury that seems almost unthinkable in today’s film industry.

Morricone may have created much of the musical language surrounding westerns – from bullwhips cracking to the twang of the jew’s harp – but as he regularly points out, they make up less than 10% of his soundtrack work. He can sometimes appear frustrated that so much focus has been on those early films, which perhaps makes it surprising that he agreed to work with Tarantino on The Hateful Eight, his first Western since 1981’s Buddy Goes West.

But of course, Tarantino’s vision is very different to that of Leone’s half a century ago, which is one of the reasons why Morricone enjoyed the challenge. “It’s not a real western,” he says of The Hateful Eight. “The music I wrote for Sergio Leone belongs to those films and that period, but with this I wanted to go more towards symphonic music or even American popular music. It was important to do something that broke with tradition.”

There was a time when the idea of Morricone collaborating with Tarantino at all seemed unlikely – in 2013 the New York Times reported him telling film students in Rome that he wouldn’t work with the director in future after Tarantino had taken the song he wrote for Django Unchained, Ancora Qui, and used it in a manner seemingly not to his liking: “He places music in his films without coherence,” was his withering verdict. But Morricone later claimed that these comments were misconstrued and that he merely found the sheer amount of blood and violence in the film to be not to his taste. This does, admittedly, make you wonder how he had the stomach for The Hateful Eight, which has come under fire for gratuitous gore, but Morricone isn’t perturbed.

“In this film, the violence is so exaggerated that you cannot take it as real,” he says. “You can easily stand it, whereas in other films the violence may be smaller in scale but more real.” He says the key to writing music as a backdrop to violence is to push musicians to their physical and mental limits.

“You have to convey this idea of violence, so you do that firstly by working on the register and timbre of the music,” he says. “You try to take each instrument’s range to the extreme. Because the suffering of the musician playing in that way – which is quite difficult – has to resemble the suffering that the victims of those violent scenes endured.”

The thought of whole tuba sections pushing themselves towards a collective coronary makes for a delightful image, and Morricone is frequently fascinating when discussing the way his music works. Schooled in the avant-garde and a member of the influential experimental collective Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza (or Il Gruppo) throughout the 1960s and 70s, he nevertheless believes his vast influence among pop artists is due to his simplicity: “I often use the same harmonies as pop music, because the complexity of what I do is elsewhere.”

Morricone will be in the UK next month for a show at the O2, and for some that will be a surprise. He was forced to postpone his last London show for a few months due to a back injury, and when he finally did appear in February 2015, to play My Life In Music, a tour-de-force that swept across his entire back catalogue, many critics assumed it was a farewell.

“I don’t care,” he says. “I am still here and still performing. When I was 35, I told my wife Maria, ‘OK, when I am 40 I will stop writing film music, and I will just write absolute music’. But I am still here writing film music, so you can never say when you will stop.”

In fact, Morricone says he doesn’t feel old at all. Shortly before he performed at the O2 he even put out a statement: “Many people have asked if this tour is my last one. This is not the case. I feel rested, inspired and excited to be back. I consider it a comeback after a terribly long period of absence.”

Watching that show, I realised just how important his emotionally loaded music had been in my own life, and marvelled at the way it seems to connect so directly and so deeply with people. For me personally, it has soundtracked moments of spine-tingling ecstasy – an epic drive through the red rocks of Sedona, for instance – and also moments of great sadness: I still have to be careful about where I hear the beautiful theme to Once Upon a Time in the West, so intrinsically linked as it is with a past breakup.

And so I end by asking how it feels to have written soundtracks not just for the hundreds of great films, but also for countless people’s lives, including mine. In the background I hear his animated Italian voice. Then his translator Gioia laughs and says: “Well, Maestro thinks that this does make him seem like a very old man!”

- Ennio Morricone performs 60 Years of Music at The 3Arena, Dublin 14 February and The O2 London 16 February

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion