I Am Your Father

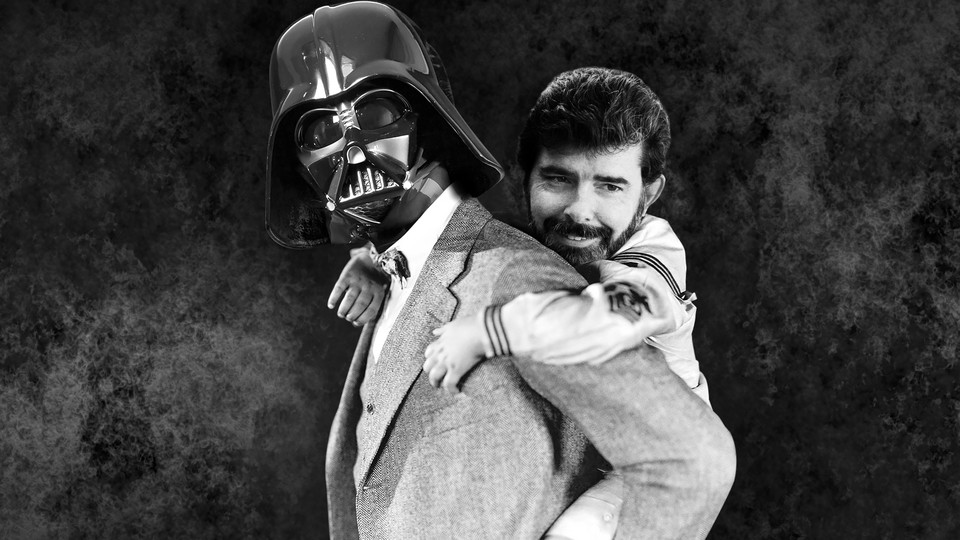

Star Wars is an eternal tale of paternal love and redemption—for both George Lucas and Anakin Skywalker.

To every child, boy or girl, a father must seem, at times, to be a kind of Darth Vader—large, tall, frightening, with a booming deep voice, insanely powerful, and at least potentially violent. For any child, boy or girl, a father is both Jedi and Sith—Obi-Wan Kenobi, gentle and calming and good, and Vader, fierce and terrifying. Of course, every father offers his own combination. But almost every one seems to have easy access to the Dark Side, at least to a child, and with his immense power, he appears capable of anything.

One of the things Star Wars is most deeply about is fathers, sons, and redemption. In its own way, it points to the indispensability of paternal love, and it has a lot to say about the lengths to which people, boys or girls, will go to get it. In the first Star Wars trilogy, Lucas was able to get quite primal about fathers and sons, and while his tale speaks to everyone, he’s given some personal hints as to why.

His relationship with his own father, George Sr., was troubled—in some ways, even tortured. It contained disappointment and mandates and prohibitions. As one of Lucas’s interviewers has noted, George Sr. was known as a “domineering, ultra right-wing businessman,” and those who “know Lucas have always insisted that the tortured relationship between Darth and Luke springs, in many ways, from Lucas’s relationship with his own father.”

Lucas’s father did not (so far as we know) try to convince him to go to the Dark Side, or to rule the universe as father and son, but he did urge him to abandon his dreams and to join him in the family business. “My father wanted me to go into the stationery business and run an office equipment store,” Lucas has said. “He was pretty much devastated when I refused to get involved in it.” By all accounts, their confrontations on this subject were turbulent, and for a time, they ended up estranged. It’s worth pausing over that. Even if it’s temporary, an estrangement between a parent and child is extraordinarily painful. (Been there, done that.) True, there were no lightsabers. No one lost a hand. But every son yearns for his father’s approval, and it was not easy for Lucas to get his.

Referring to himself and Steven Spielberg, Lucas once noted, “Almost all of our films are about fathers and sons. Whether it’s Darth Vader or E.T., I don’t think you could look at any of our movies and not find that.”

Lucas himself was able to reconcile with his father, though it took years for that to happen. He packs a lot of pain and understanding into these words: “He lived to see me finally go from a worthless, as he would call ‘late bloomer’ to actually being successful. I gave him the one thing every parent wants: to have your kid be safe and able to take care of himself. That was all he really wanted, and that’s what he got.”

It’s not irrelevant that after Return of the Jedi, Lucas abandoned Star Wars, and movie-making, for just one reason: He wanted to be a good father. He retired for two decades so that he could raise his children. Asked in 2015 what he wanted the first line of his obituary to say, he responded without the slightest hesitation: “I was a great dad.”

The first two trilogies of Star Wars—Lucas’s half dozen—should be called “The Redemption of Anakin Skywalker.” The redemption occurs as a result of intense attachment, otherwise known as love. That form of attachment is the whole reason for Anakin’s descent to the Dark Side. It’s why he falls; he can’t bear to lose his beloved. Anakin’s heart is what gets him into trouble.

Attachment is also the reason for his choice to return to the Light. He can’t bear to see his son die. In the end, Star Wars insists that you can’t be redeemed without attachment. That’s the strongest message of the saga, and that’s what makes it speak to people’s deepest selves. Redemption has everything to do with forgiveness. If you are forgiven, most of all by yourself, you can be redeemed. Luke forgives his father. (A good lesson for children everywhere: If Luke can forgive the worst person in the galaxy, just about, then surely any parent can be forgiven. A good lesson for grudge holders, too. Let it go.)

Even toward the end, Luke is willing to give Vader that supreme gift. He redeems him through that forgiveness. As Lucas said, “Only through the love of his children and the compassion of his children, who believe in him, though he’s a monster, does he redeem himself.”

(In The Force Awakens, Han has precisely the same attitude toward Kylo, his son, as Luke did toward his father, Kylo’s grandfather. True, that didn’t work out so great. But just wait. For the third trilogy, I predict that some redemption is on the way, and for more than one character. You’ll see.)

In A New Hope, Anakin is the satanic figure, the embodiment of evil. He is made good because his son insists on seeing good in him, and chooses to loves him, and because in the end, he chooses to love him back.

The redemption scene is preceded by a vicious fight between father and son. (Every son wants that, a lot, and also hates and is terrified by the idea.) Vader ought to win, as he did in The Empire Strikes Back; he is far bigger and appears stronger. But trained by Yoda, Luke succeeds in gaining the upper hand. Vader is forced back, losing his balance, and he is knocked down the stairs. Luke stands at the top, ready to attack. On the verge of victory, he refuses to do so. With his soft, youthful voice he says, “I will not fight you, Father.” In his menacing baritone, Vader responds, “You are unwise to lower your defenses.” As Vader senses that Luke has a sister, he threatens her with a kind of finality: “Obi-Wan was wise to hide her from me. Now his failure is complete. If you will not turn to the Dark Side, then perhaps she will.”

It’s at that stage that Luke falls into a Dark Side rage and slashes off his father’s right hand at the wrist (a kind of emasculation). Vader is at his son’s mercy. The Emperor to Luke: “Good! Your hate has made you powerful. Now, fulfill your destiny and take your father’s place at my side!” But rejecting what he himself is becoming, Luke refuses to commit patricide: “You’ve failed, Your Highness. I am a Jedi, like my father before me.” It is then that the Emperor tries to kill Luke, hurling lightning bolts at him. Christlike, Luke asks, “Father, please. Help me.” At the last possible moment, Vader lifts the Emperor and hurls him to his death, saving his son; but Vader himself is dying.

Here’s the redemption scene:

Darth Vader: Luke … help me take this mask off.

Luke: But you’ll die.

Darth Vader: Nothing … can stop that now. Just for once … let me … look on you with my own eyes.

[Luke takes off Darth Vader’s mask one piece at a time. Underneath, Luke sees the face of a pale, scarred, bald-headed old man—his father, Anakin. Anakin sadly looks at Luke but then gives a tired smile.]

Anakin: Now … go, my son. Leave me.

Luke: No. You’re coming with me. I’ll not leave you here, I’ve got to save you.

Anakin: You already … have, Luke. You were right. You were right about me. Tell your sister … you were right.

[Anakin smiles and his eyes begin to droop, slumping down in death while giving one last dying breath.]

For a fairy tale, that’s good. Actually, it’s very good. It’s even great. And a nice bit from the novelization: “The boy was good, and the boy had come from him—so there must have been good in him, too. He smiled up again at his son, and for the first time, loved him. And for the first time in many long years, loved himself again, as well.” (One reason we love other people is that they help us to love ourselves. Luke did that for Anakin, and Han tried to do it for Kylo.)

The sheer quality of the dialogue here is a bit of an upset. Lucas knows myth, and he has a spectacular visual imagination, but most of the time, emotions are not exactly his strong suit. While he enjoys editing, he doesn’t always like working with people. (In the prequels, it’s droids and more droids. Droid armies everywhere. All droids, all the time.) Harrison Ford famously told him, “You can type this shit, George, but you can’t say it.” He confesses that he struggles with dialogue. He has said, “I think I’m a terrible writer.” Once he admitted, “I’d be the first person to say I can’t write dialogue … I don’t particularly like dialogue, which is part of the problem.” And as Ford remarked in an interview, “George isn’t the best at dealing with those human situations—to say the least.”

But at the crucial moment in the original trilogy, Lucas delivered. He was the best at dealing with that particular human situation. And he knew exactly what he was doing. On this count, he didn’t trick anyone.

Lucas had a lot of sources; for Luke’s journey, his major one was Joseph Campbell’s tale of The Hero With a Thousand Faces. The whole series tracks Campbell’s account. But the notion of a father sacrificing himself, and repudiating the cause of his entire life, and dying, in order to save his son? That’s Lucas’s own. It’s highly original.

That’s what tops “I am your father.”

The prequels are ostensibly about one thing above all: the perils of attachment. In Anakin’s own words: “Attachment is forbidden. Possession is forbidden.” Yoda’s words: “Let go of fear, and loss cannot harm you.” Evidently influenced by Buddhism, Lucas self-consciously portrayed a person turning to evil because he could not “let go”—of his mother and of his beloved. Fear of loss is Anakin’s downfall. And of course this theme looms large in Luke’s story as well. Luke is reckless and vulnerable to the Dark Side because he is terrified of losing the people he loves. “His friends were in terrible danger, and of course he must save them.”

Once more, Yoda’s words: “Train yourself to let go of everything you fear to lose.” Yoda again: “Of the Dark Side, despair is.” The reason? “Even despair is attachment; it is a grip clenched upon pain.”

The point here is plain: If you are attached to someone, you become vulnerable. Recall Yoda’s famous words: “Fear leads to anger, anger leads to hate, hate leads to suffering.” Serene detachment is the best path, and the only safe one, because it prevents catastrophic choices. Luke nearly fails as a Jedi Knight because of his rage, produced by Vader’s vow to pursue his sister. Anakin does fail as a Jedi Knight because he is incapable of detachment; he is desperate to find a way to bring his loved ones back to life. As Lucas put it, “His undoing is that he loveth too much.”

The Sith get their revenge only because of Anakin’s fear of death— not his own, but of the people he loves. Anakin chooses disastrously as a result of that fear. And in fact, distinguished strands of both Western and Eastern philosophy argue strongly in favor of detachment. Both Stoicism and Buddhism make pleas for detachment, and in emphasizing the perils associated with fear of loss, the Star Wars movies borrow heavily from those traditions. As the philosopher Martha Nussbaum notes, “The Stoics think you should never mourn,” and “Cicero reports that a good Stoic father says, if their child dies, ‘I was always aware that I had begotten a mortal.’”

But in Return of the Jedi, Anakin is redeemed not by serenity and distance but by their opposite. He chooses to kill the Emperor because he cannot bear to see his son die. (So much for those silly Stoics. Chose that, Anakin did.)

Whatever Yoda said, Anakin ends up being redeemed by fear of loss and by love, not detachment—and so he is, when making the redemptive choice, perfectly continuous with his earlier self, showing the very characteristics that led him to the Dark Side. When Lucas pressed that point, the Force was unquestionably with him. In terms of narrative, that’s his finest moment.

The Redemption of Anakin Skywalker transcends any individual’s personal struggles. Its real theme is universal. By their innocence and goodness, by their boundless capacity for forgiveness, and by the sheer power of their faith and hope, children redeem their parents, bringing out their best selves. And as every child knows, deep in his heart, any parent is likely to choose to risk his life to save his child’s, even if it means a contest with the Emperor himself. When he makes that choice, the Force is going to be right there with him.

I like that, and I believe it.

This article has been adapted from Cass R. Sunstein’s forthcoming book, The World According to Star Wars.