What's Actually in the Magna Carta?

The document is celebrated as the foundation for constitutional democracy. So why does it spend so much time on forests and fish traps?

In 2012, David Cameron spent an excruciatingly long two minutes discussing the Magna Carta with David Letterman. The British prime minister struggled to name the location where the iconic English document was signed and the whereabouts of the original copies. But he perked up when describing the charter’s significance. “The big moment of the Magna Carta was basically people saying to the king that other people have to have rights”—it was about “the crown not being able to just ride roughshod over everybody,” he said. Then the soaring moment hurtled back to earth. “And the literal translation [of Magna Carta] is what?” Letterman asked. Cameron had no idea.

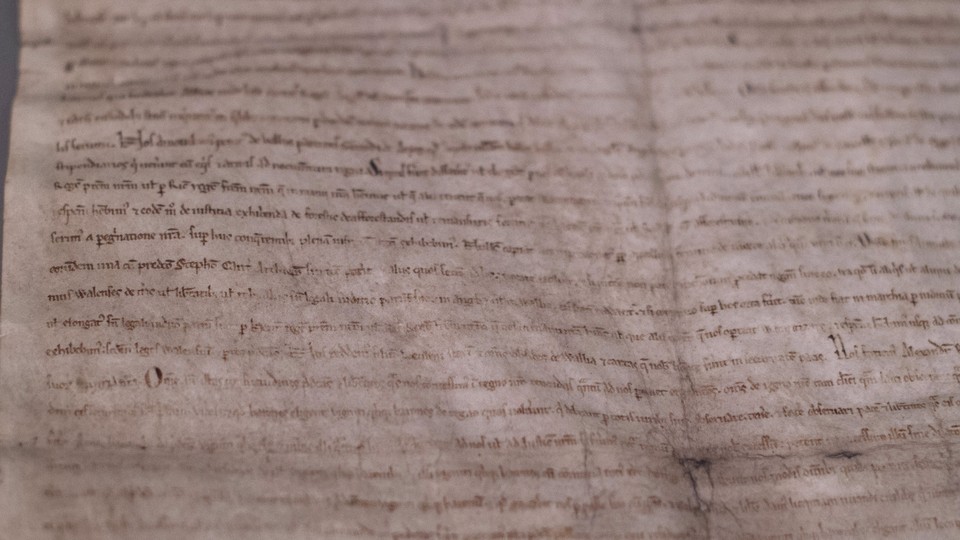

The Magna Carta (“Great Charter”), which turns 800 years old on Monday, is often invoked in the U.K., the U.S., and around the world as a font of freedom, the touchstone for today’s constitutional democracy. But its specifics are largely forgotten. And what you realize in combing through the document, which was originally written in Latin and runs to about 4,500 words in English, is this: Those specifics are incredibly specific, which makes the charter’s widespread and enduring appeal all the more surprising.

Cameron, for instance, didn’t mention King John’s pledges to English barons to “at once return the son of Llywelyn, [and] all Welsh hostages” and bar from royal service the relatives of Gerard de Athée, namely “Engelard de Cigogné, Peter, Guy, and Andrew de Chanceaux, Guy de Cigogné, Geoffrey de Martigny and his brothers, Philip Marc and his brothers, with Geoffrey his nephew.” The British leader failed to cite the clause specifying that “no constable may compel a knight to pay money for castle-guard,” or the one noting that “inquests of novel disseisin, mort d’ancestor, and darrein presentment shall be taken only in their proper county court.”

“It’s amazing, isn’t it: Here we are celebrating a document that hardly anybody understands when they actually look at it,” BBC presenter Dan Damon marveled on Friday.

Consider a selection of lines from the acclaimed text:

- “If a man dies owing money to Jews, his wife may have her dower and pay nothing towards the debt from it.”

- “No town or person shall be forced to build bridges over rivers except those with an ancient obligation to do so.”

- “All fish-weirs shall be removed from the Thames, the Medway, and throughout the whole of England, except on the sea coast.”

- “There shall be standard measures of wine, ale, and corn (the London quarter), throughout the kingdom. There shall also be a standard width of dyed cloth, russet, and haberject, namely two ells within the selvedges.”

- “All evil customs relating to forests and warrens, foresters, warreners, sheriffs and their servants, or river-banks and their wardens, are at once to be investigated in every county by twelve sworn knights of the county, and within forty days of their enquiry the evil customs are to be abolished completely and irrevocably.”

- “No one shall be arrested or imprisoned on the appeal of a woman for the death of any person except her husband.”

These lines lack something of the timeless tenor of “We hold these truths to be self-evident.” And that’s by design. The barons who drafted the Magna Carta in 1215 weren’t, in the main, revolutionaries proclaiming a new political system and establishing its dimensions for posterity. They were aristocratic rebels who felt King John had abused his rights under the existing feudal system as he waged war with France (and with the barons themselves). They were champions of the status quo ante, advocating innovative, enforceable solutions to rein in the crown.

More than a third of the document’s 63 clauses defined the limits of the king’s rights. And they all made sense at the time. Restrictions on debts to Jews came during a period when many Jews, who were religiously permitted to offer interest-bearing loans to Christians, worked as money-lenders—a service the barons at once utilized and resented, especially since the king often seized their property when debts went unpaid. The barons wanted to stop King John from forcing people to “build bridges over rivers” solely so he could hunt in certain areas. “Fish-weirs,” or V-shaped wooden fish traps, were clogging up waterborne commerce, threatening free navigation on English rivers. All the esoteric talk about russet, haberject, and ells clouds one of the Magna Carta’s most lasting legacies: an effort to standardize weights and measures to facilitate trade. The “evil customs” in the forests refer to King John’s harsh ordinances governing royal woodlands, not to witchcraft or sinister satyrs. The clause barring women from testifying against murder suspects may have been intended to prevent men from pressuring women into making false accusations, though it’s difficult to interpret the provision as anything but discriminatory.

Some parts of the Magna Carta have proven more durable. Clauses 39 and 40, which include the famous line, “To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice,” helped establish the concept of legal due process. The seeds of the British Parliament and the notion of “no taxation without representation” are present. But as Jill Lepore wrote in The New Yorker earlier this year, “Much of the rest of Magna Carta, weathered by time and for centuries forgotten, has long since crumbled, an abandoned castle, a romantic ruin.”

The document’s potency derives less from specific clauses than from the pliable idea it committed to parchment: that no one, including the king, is above the law. King John managed to get the Magna Carta annulled by the pope just months after it was signed, but his successor reissued a version of it, and a parade of versions followed. The document’s core idea flickered in and out of English politics for centuries, before being rekindled during a parliamentary struggle against the crown in the 17th century and spreading to the British colonies, where it acquired new form and strength and influenced the U.S. Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights. Some Founders glorified the charter as a guarantor of the English liberties they now claimed for themselves, while others recognized its unfinished business. The Magna Carta “does not contain any one provision for the security” of rights such as “the trial by jury, freedom of the press, or liberty of conscience,” James Madison observed in 1789.

“What Magna Carta initiated … was constitutional government,” the British politician Daniel Hannan recently wrote in The Wall Street Journal. “The law was no longer just an expression of the will of the biggest guy in the tribe. Above the king brooded something more powerful yet—something you couldn’t see or hear or touch or taste but that bound the sovereign as surely as it bound the poorest wretch in the kingdom. That something was what Magna Carta called ‘the law of the land.’”

This tension between the Magna Carta’s timeless appeal and time-sensitive substance reflects a larger debate about the benefits and dangers of one generation establishing a constitution for future generations to follow—a debate that James Madison and Thomas Jefferson once engaged in. In a letter to Madison in 1789, Jefferson floated the idea of every constitution and law expiring and coming up for re-ratification after 19 years—his rough estimate for the length of time that a generation would wield power, based on mortality statistics he consulted. “[N]o society can make a perpetual constitution, or even a perpetual law,” he wrote. “The earth belongs always to the living generation.” But Madison expressed concern about the instability that would result from “a Government so often revised,” pointing out that “improvements made by the dead form a charge against the living who take the benefit of them.”

Madison’s analysis could well apply to the Magna Carta. Over the years, the document has been molded and remolded, its anachronisms shed and its resonant clauses reinterpreted. Discussion of fish-weirs and haberject long ago receded; the improvements to the rule of law that a bunch of rebellious English barons made—deliberately or not—remain.