These days, whenever a group of roboticists gets together to talk shop, the subject almost inevitably turns to Google and its secretive robotics division. What are those guys up to?

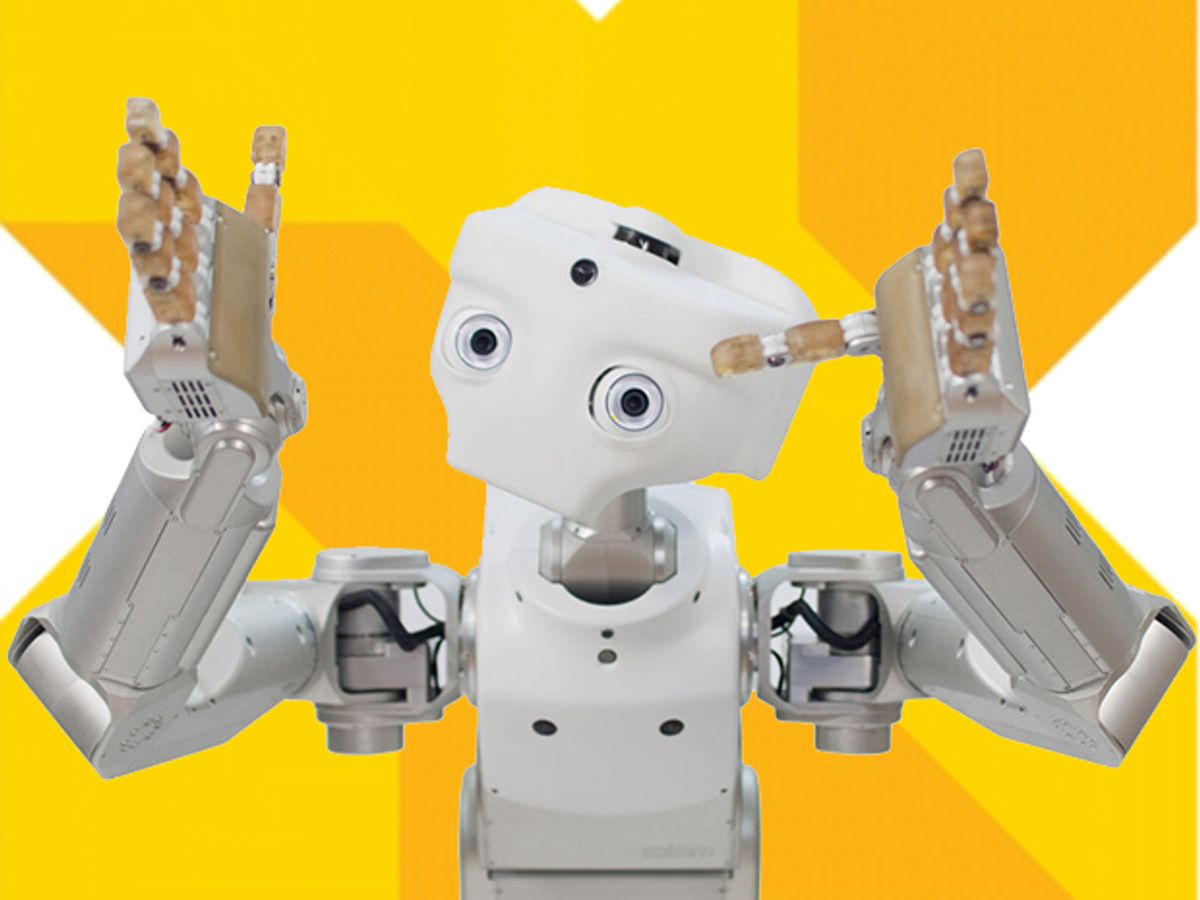

The curiosity is understandable. It’s been nearly three years since Google made its huge move into robotics by acquiring an impressive and diverse group of companies, including Meka and Redwood Robotics, Industrial Perception, Bot & Dolly, Holomni, Autofuss, Schaft, Reflexxes, and, most notably, Boston Dynamics. Google’s robotics division, which has some of the world’s brightest robotics engineers and some of the most advanced robotics hardware ever built, has been working quietly at various secluded locations in California, Massachusetts, and Tokyo, and details about their plans have been scarce. Earlier this year, following Google’s reorganization as Alphabet, the robotics unit became part of X, Alphabet’s experimental technology lab, or as the company calls it, its “moonshot factory.”

Now the robotics community’s curiosity has reached a new height after news broke that Alphabet is reportedly selling Boston Dynamics, according to sources who spoke to Bloomberg. The revelation surprised many observers, but what they say was most confounding were reports suggesting that Alphabet wants to get out of robotics altogether. Is the company done with robots? Is the robotics group being disbanded?

That’s not what is happening, the company says. “X has always been the home of long-term projects that involve both hardware and software, and we have a number of projects related to robotics already (e.g. Project Wing and Makani), as well as the lab facilities that are helpful for this kind of work,” Courtney Hohne, an X spokesperson, said in a statement provided to IEEE Spectrum. “We’re now looking at the great technology work the teams have done so far, defining some specific real-world problems in which robotics could help, and trying to frame moonshots to address them. We want to fall in love with a problem, not with a specific technology.”

The search for moonshots will probably continue to be a matter of intense debate internally. For those outside the company, it’s a captivating issue, and everyone seems to have a different opinion on what Alphabet could or should do with its robots. In fact, some roboticists encouraged us to gather those opinions in a public place to stimulate the debate. We liked the idea, so we contacted nearly 50 robotics people with a variety of different backgrounds and asked them the following question:

If you were in charge of Google’s robotics division and you had all those robotics companies at your disposal, what would you do? What kinds of robots would you build and for what markets?

Many declined to comment, citing ties to Alphabet. Others said they didn’t have a good answer (as one Japanese robotics executive put it, “I know exactly what I want to do with my robot business. Sorry, but I have no idea about Google.”) And despite our prodding for respondents to dream up wild ideas, no one suggested anything too crazy (Meka-BigDog hybrid centaur robot to deliver mail, anyone?).

But we did receive over a dozen thoughtful comments, which we’re including below. Alphabet and its robotics group certainly face huge challenges as they decide what to do next. We hope the ideas here will help advance the discussion about how to take robots out of labs into the real world. Commercial success in robotics, after all, is important not only for Alphabet, but for the future of our entire industry.

After you read through these comments, we’d love it if you could let us know what you think, too: contribute to the discussion by sharing your opinions or ideas in the comment section.

Comments have been edited for clarity and length.

Colin Angle, co-founder, CEO, and chairman of iRobot

“The group of companies Google bought seemed best suited to work on warehouse automation or more interestingly, the last 10 feet of commerce. What’s the point of a self-driving delivery vehicle without some way to get the package to the door? The challenge would be aligning all the disparate agendas and interests of the companies into a focused project. And my last 10 feet of commerce idea would require some real amount of patience. But it would be world-changing.”

Jean-Christophe Baillie, former chief science officer of Aldebaran Robotics and founder and president of Novaquark

“The core issue we are dealing with here is the realization that making robots that actually do things in the real world is much more difficult than what we had envisioned. Yes, progress has been made, like what Atlas is doing with stabilization and walking, but, sad to say, this is still the relatively easy part of the problem. The hard part is AI. I tend to believe that we cannot brute force our way to solve the complex problems of interaction with the environment or, even more difficult, with people.

In any case, this makes finding applications for humanoid robots like Atlas all the more difficult. I guess it could be used by the military to transport heavy payload in mountainous environments where a tracked vehicle isn’t good enough. But what about autonomy? Perhaps in nuclear plants, if the hardware is designed to withstand the harshness of a radioactive environment. Perhaps it could be used as a logistics assistant in warehouses, or for delivery?

Now, on the fun, not-so-serious side: maybe a humanoid robot could be used to compete in the 100-meter race in a future Olympics? A sort of athletic version of AlphaGo: Can we defeat the best human runners?”

Ilian Bonev, professor at École de Technologie Supérieure in Montreal, Canada, and co-founder of Mecademic

“Google recently showed that they have developed a novel seven-axis industrial robot that looks collaborative. With all the intelligence they clearly plan to embed in the robot, it could become a direct competitor to Rethink Robotics’ Sawyer, and probably other co-bots as well. In fact, they seem to be hiring more and more industrial robotics experts, including engineers familiar with systems like the Kuka LBR iiwa and Fanuc robots.

Remember, Universal Robots was sold for some US $350 million, and all they do is three models of collaborative robots; less sophisticated compared to Boston Dynamics’ robots. Yet Boston Dynamics is probably worth much less than $350 million. For me, it’s a no-brainer that Google is focusing on the industrial robots market. If I were a Google executive, I would probably acquire Fetch Robotics for warehouse applications. Possibly acquire Robotiq too. Definitely sell Schaft.”

Gary Bradski, founder and CEO of OpenCV and vice president for advanced perception and intelligence at Magic Leap

“To get at what I would do, I have to use an exact analogy. Google created ‘Google Express,’ a delivery service to compete directly with Amazon’s increasing distribution of goods. It’s an (obviously doomed to me) attempt to be the delivery service and earn billions. It must be a huge money loser for Google right now where instead, they could have just leveraged their web services to help enable a market. . . . Google should have just focused on creating an easy way for businesses and consumers to sell to each other. Work with Uber and Lyft to make delivery easy but where Google is just paying for electrons on a web server, not actual cars and workers. I’d do the same thing for robotics.

First of all, I’d partner to get someone to actually make the small city street robotic cars, and with them would come the aftermarket work of delivering goods between businesses and people. I’d do the same with the rest of robotics: Make a cloud storage for robotics systems with great tools such as TensorFlow deep neural network engine, but with great debug, network tuning visualization tools, guarantee of data integrity and uptime, ease of scaling, and so forth. Make a market in trained deep networks and let others run with improving robotics. Make a market for sensors, actuators etc., but don’t make them yourself. Offer all the other Google services: speech, maps, chat, mail, image recognition, adsense (imagine a robot cart in a supermarket that can offer you coupons to switch brands as you buy them), and add the above ability to buy and sell all in ways that can work with new robots in homes and businesses.

If Google does this, then they automatically get a share of the winners without having to be the winner. They also get a grand view of robotics and can wisely invest in opportunities as firms try to develop new areas or as firms are winning in their respective areas. . . . Google’s forte is this kind of back-end services and front-end software and tools. Play to your strengths, business rule #1.”

Martin Buehler, executive R&D imagineer at Walt Disney Imagineering, IEEE Fellow

“There are many exciting robotics application areas like logistics (industry, order fulfillment, hospitals, hospitality), home bots, surgery, etc. but I think a better match is software: Take ROS to the next level (as an on-board OS, plus cloud components for AI, learning, perception, skill sharing, etc.) as an open source, transformative enabler for the nascent robotics industry, and reap the benefits. Monetize by funding/acquiring the most promising startups (hardware and software), charge for premium cloud services, and generally organize the world of robot information.

As for mobile/legged robotics, the place I believe they have the best chance of having impact in the near term is in Disney Parks—we have lots of legged characters that are anxious to come alive in our parks across the world right now. We have a business case, and we are hiring!”

Henrik Christensen, professor of robotics and executive director of the Institute for Robotics and Intelligent Machines (IRIM) at Georgia Tech, IEEE Fellow

“To me the use-cases for Google robotics are obvious:

1. The big driver would be e-commerce. Today, most people go straight to Amazon for online purchases, which implies that Google is losing advertising revenue to Amazon. Google should engaged in e-commerce services such as Google Express that can get more revenue back. To make it economically tractable, you would like to have robots for loading/unloading trucks and for pick up and packaging of material for shipping. Expertise from Industrial Perception and Meka are clear candidates for this.

2. Google has spent serious money on small series electronics manufacturing for Google Glass, phones, and wearable devices. Having their own small series manufacturing capability would be a major cost reduction for them.

3. New types of home robots have a lot of potential to generate new data about use patterns for occupants of homes that will allow companies to build new services, help homeowners save electricity, and do certain functions (e.g. vacuuming) when no one is around, and other functions when people are around.

4. Boston Dynamics’ experience with robots that can traverse any terrain could allow Google StreetView/mapping of any area on earth, not only the areas where you can drive a vehicle. The BD robots are great platforms for automated mapping and opens up more possibilities for [geographic information system] services. Especially if it’s possible to combine these applications with autonomous capabilities developed at Schaft.”

Ryan Gariepy, CTO of Clearpath Robotics

“Google has a balance sheet most startups can only dream of, experience with mass production of consumer products, excellent videoconferencing software, significant brand equity with consumers, low-cost and low-power SLAM systems, and incredibly effective facial and speech recognition systems. If anyone could crack the indoor social robot market that is seeing such high interest right now in both the consumer and commercial spaces, it would be them.

Of course, this doesn’t necessarily use the entire spectrum of robotics technology and team they brought in to their company a few years ago nor would it make privacy advocates feel particularly at ease, but it does open the door for robotics to be truly commonplace in day-to-day life.”

Michael A. Gennert, professor of computer science and director of the robotics engineering program at Worcester Polytechnic Institute

“Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information. Robotics gives the company the ability to act on that information on a massive scale. Google already has enormous amounts of information on humans in general (our queries, our locations from Android, our tasks, our likes and dislikes, etc.) and individuals. Put that knowledge together with mobile robots and you’ve got Companion Bots (or Helper Bots).

Similar to the way the iPhone combined several devices (messaging, phone, iPod, watch), the Companion Bot combines telepresence, interaction, manipulation. You want the interaction of Jibo (not acquired by Google) with the manipulation of Meka with the mobility of Boston Dynamics and Schaft and the learning of DeepMind. The market is huge. One might need versions for children, the elderly, health, and other industries. You’d have to keep the mechanisms as simple as possible—that’s where the unit cost is. But the value is in the software—that’s where the development cost is.”

Vijay Kumar, professor of robotics at the University of Pennsylvania, IEEE Fellow

“Robotics is hard. Everyone claims that once one builds abstractions for hardware, robotics is a software problem. And indeed it is becoming easier to build hardware (I agree with much of what has been said in this article). But there are substantial challenges in the hardware/software interfaces mostly because software is fundamentally discrete while hardware must interact with the continuous world. While this distinction may not be important in autonomous drones and self-driving cars, it is a major problem in tasks that require physical interaction (e.g., contact) with the real world.

Boston Dynamics has the world’s experts in actuation, sensing, and control, particularly using hydraulics, and they are focusing on very difficult problems in legged locomotion, balance and agility. Where else could one use these kinds of systems? Clearly in tasks that require manipulation. Legs are like arms; stability and robustness in balance translate to similar properties in grasping and dexterity, and controlling locomotion is not unlike controlling manipulation. And we know that two-year-olds are more dexterous than our best robots. So there is a huge play to be made in manipulation, particularly in industry where the use of hydraulics is acceptable.

So think of any of the wide range of applications that require robots to operate on the manufacturing shop floor, in warehouses, in automated storage and retrieval systems, in military logistics operations (which by the way is a huge fraction of the cost for our DoD), and in maintenance in power plants and reactor buildings—you need BD-like solutions.

[About the other Google robot companies], I agree with Gary Bradski when he says Industrial Perception technology is a ‘ladder to many moons’: warehouse robots, tending stores (we are working with Walgreens for this), home robots for the elderly (which I firmly believe we’ll have in five to 10 years), robots helping hotel guests (Savioke is already doing this). Meka and Redwood are also in the manipulation space. But if I were in charge, I would take BD and Industrial Perception and target the applications I talked about above.”

Robin Murphy, professor of computer science and engineering and director of the Center for Robot-Assisted Search and Rescue (CRASAR) at Texas A&M University, IEEE Fellow

“If I were a large company with deep pockets, I would accept that robotics is what is called a ‘formative’ market and just like shopping on the web, it will take a decade or so to ramp up. Robots are innovations that do not directly replace people and thus it is hard for people to imagine how to use them—thus the market is formative. The theory of diffusion of innovation indicates that potential end-users, not developers, need to experiment with applications to see what works (and not just physically but human-robot interaction as well).

However, robots have to be extremely reliable and the software customizable enough to allow the end-users to tinker and adapt the robots, so that the end-user can find the ‘killer app.’ Essentially, you can crowdsource the task of finding the best, most profitable uses of robots, but only if you have good enough robots that can be reconfigure easily and the software is open enough. I would concentrate on creating generic ground, aerial, and marine robots with customizable software and user interfaces in order to enable their regular employees (and customers) to figure out the best uses.

In order to make sure the development was pushing towards the most reliable, reconfigurable, and open robots possible, I suggest the developers focus on the emergency response domain. Disasters are the most demanding application and come in so many variations that it is a constant test of technology and users. Imagine the wealth of ideas and feedback from fire rescue teams, the Coast Guard, and the American Red Cross, just to name a few! Focusing on emergency management would also have a positive societal benefit.”

Paul Oh, professor for unmanned aerial systems and director of the Drones and Autonomous Systems Lab at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas

“Shortly after Google bought these robotics companies, I had discussions with many colleagues from academia, industry, and government about what they thought Google was going to do. My own opinion was that ‘Google is an information company,’ and that a next-gen supply-chain would demand real-time and comprehensive monitoring and material-handling. I speculated that robots that can walk (Boston Dynamics, Schaft), manipulate (Redwood, Meka), see (Industrial Perception, Bot & Dolly), coupled with AI (DeepMind), would enable the realization of a next-gen supply-chain. About half of my colleagues said that’s really interesting… the other half said I gave Google too much credit!

Why is that important? Being able to know the ‘pulse of the supply-chain’ provides a lot of information about the parts, where they came from, who ordered them, and where they are going. Material-handling robots that pack, load, unload, stack, deliver, etc. provide the means to ‘measure’ (and possibly control) the supply-chain. . . . I was (pleasantly) surprised to see the latest Atlas perform material-handling tasks by lifting and carrying boxes.”

Nic Radford, co-founder and CTO of Houston Mechatronics

“There is a vast canyon between what gets views on YouTube and what makes money in the robot business. Would-be startup robot companies have long struggled with relevance and cost effective solutions to real world problems. Yes, we can ‘lab robot’ the heck out of any demo, but put in the field and robots like humanoids are rather flat-footed, literally, and show little hope let alone a palatable cost model. That’s not saying that a technology like a humanoid robot couldn’t find a multi-million dollar per unit market, but the robot sure as hell better work really well. And probably the only potential one is the military, something Google would likely stay away from.

In order to get ‘doors that open like this, and not like this,’ the trick is not to sell the whole humanoid, because it’s worth far more if you focus on the technologies that make up that humanoid. If you know how to monetize it properly, everything from the hierarchical distributed control architectures, user abstraction layers, actuators, perception, etc. basically all the stuff that makes up the robot can be applied to industries literally begging for robot tech innovation right now.

So what would I do with a string of companies like the ones that Google picked up? Well, here at HMI, the case was clear and we’re tackling it already, but I’d point them all in the direction of a multi-trillion dollar oil and gas market that really hasn’t seen any robot innovation for… well… never, and a market that is currently very open to adopting robotic solutions.

Quite candidly, if Google does decide to part ways with Boston Dynamics, I think it would be a massive mistake on their part. Google is probably one of a handful of companies with the resources to actually solve the humanoid robot challenge. And it is a solvable problem; it just requires some significant investment and tenacity to leave them alone and let them work. But unfortunately, for better or worse, the problems that are making money in robotics today and tomorrow on the surface are far less sexy. And I think not even Google can keep financing robotics where the end-game is so unclear.”

Mark Silliman, CEO at Bold Robotics

“Keep in mind Google’s strategy from day one. Be the epicenter of information flow, not the generator of content or physical products (obviously there is the Chromebook now but even that is produced by competitive third parties). If I was going to guess, Google is far more interested in becoming the data protocol of choice for IoT (allowing various robots/sensors/machines to communicate over networks) as opposed to making specific hardware.

For instance, I doubt they’ll actually produce a production automobile for the masses. Instead they’ll want to control how many competitive automobile companies vehicles ‘think’ and ‘communicate.’ Point is: king of software, not hardware. Similar logic will be applied well beyond automobiles of course.”

Siddhartha Srinivasa, professor of computer science and director of the Personal Robotics Lab at Carnegie Mellon University

“Google has delivered visionary search technology but sadly seems to struggle when it tries to do anything else. [About Boston Dynamics,] if you acquire a humanoid robot company, you shouldn’t be surprised they produce (awesome) videos of humanoid robots that might worry some people and raise questions about robots and jobs. As a company, Google has the great potential and the resources to build technology that can actually help people.

There are over 6 million people in the United States alone who are in need of assistive care and whose quality and dignity of life depends crucially on caregivers (who are increasingly harder to find and expensive to employ). Developing caregiving robots requires the marriage of hardware, algorithms, interfaces, software engineering, and user studies. I believe Google has the breadth of expertise to address this problem. And, it has the monetary backing to deploy caregiving technology in the real world. That is what I would do.”

Tandy Trower, founder and CEO of Hoaloha Robotics

“If I had all that robot technology I wouldn’t do anything different than I am doing now, i.e. I would purpose them to build companion robots for seniors! Keep in mind that I see Hoaloha Robotics less as a robotics technology company and more as a robotics applications company. For us, robotics is a means to an end. Our development is less focused on general robotics and more focused on how we can apply related technology to human challenges. In other words, our goal is not about human replacement, but human augmentation.

So what exactly would I do? I’d have [Aaron] Edsinger apply his innovative humanoid Meka technology to a next generation of what I am building now. Holomni might be able to improve on the omnidirectional drive we are developing now. Leila Takayama was a very impressive HRI social researcher at Stanford who studied under the late Dr. Cliff Nass, who served as an academic advisor to Hoaloha Robotics. I am certain how to put her to work. Similarly, Crystal Chao, who worked under Andrea Thomaz at Georgia Tech; she did some great research on human-robot interaction too.

Shaft and Boston Dynamics would still be a challenge on how to apply. Maybe they could use their technology on some exoskeleton work or other scenarios. For example, are there firefighter/search-and-rescue markets or construction industry applications? Don’t we still need robots to be able to help with the disaster cleanup at Fukushima? It seems like this technology would be a great fit for tasks where the environment is toxic to humans. How about space exploration? For Bot & Dolly, I’d probably want to consult with Spielberg and Lucas.”

Bram Vanderborght, professor of robotics at Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium

“I would look at the core competencies of Google, and a major one is providing information to the user in an easy way over different technology platforms. These platforms went from computers to smartphones (and wearables) and so a logical next step is robotics. I would make robots that everyone in the world would use several times during the day. So that means no prostheses, exoskeletons, rescue robots, and so forth, since they are for too specific markets.

I would also not forget how to make money from it. Google mostly earns money with its advertising business and also with the app store (Google Play). So by having robots, Google would be able to collect more information about users, their habits and interests, so it could further personalize the ads, maybe even to the point where the robot itself decides what to buy for the consumer. Moreover I would make an Android-like OS for robots that developers can create apps on, so that special apps for all kinds of purposes become available, including for children, the disabled, etc.

I’d start with socially interactive robots, so that all complexity of the robot is hidden, and the robot uses speech, emotions, and gestures to easily and intuitively communicate and provide information. So I think I would go for platforms like Pepper and Jibo (and create my robot OS as a platform independent system, so other companies can develop robots with it as well). As a result, several companies would be able to be formed around the Google robot and the OS. They will have a good wireless connection so that most of the processing power is done in the cloud, and the robots can learn from each other.

In the long term, I’d want that the robots are able to perform physical tasks at home and in offices. To achieve that, the robots would learn by collaborating with humans in manufacturing settings, which are more controlled environments and the expectations are different. This approach would lead to robot capabilities that I could gradually role out for the consumer market.”

Manuela Veloso, professor of robotics at Carnegie Mellon University, IEEE Fellow

“I would focus on finding out more about what are the needs of society that could benefit from robotics. Education, health, service. Based on my own research, I am biased towards service robots, like the CoBots we’ve been developing at my lab. The idea is using multiple autonomous mobile robots to perform service tasks like transporting things, mapping and monitoring the environment, and providing information to humans as well as guiding them through our indoor spaces.

An important requirement is that the robots need to do all those tasks in a very reliable and robust way. We were able to accomplish that by adopting novel approaches, such as our concept of symbiotic autonomy, in which the robots are aware of their perceptual, physical, and reasoning limitations and proactively ask humans for help. For example, if a robot is delivering mail, it will ask a person to put the papers into its basket, or if it’s going to another floor in the building, it will ask a person to push the elevator buttons. With a little help from humans, robots will go a long, long way.”

Erico Guizzo is the Director of Digital Innovation at IEEE Spectrum, and cofounder of the IEEE Robots Guide, an award-winning interactive site about robotics. He oversees the operation, integration, and new feature development for all digital properties and platforms, including the Spectrum website, newsletters, CMS, editorial workflow systems, and analytics and AI tools. An IEEE Member, he is an electrical engineer by training and has a master’s degree in science writing from MIT.

Evan Ackerman is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. Since 2007, he has written over 6,000 articles on robotics and technology. He has a degree in Martian geology and is excellent at playing bagpipes.