SAN FRANSCISO—At a Kickstarter launch party in a swanky downtown hotel, employees and friends of year-old company Fove milled about, ready to talk to anyone and everyone about their contributions to a new virtual reality headset. VR headsets are old news at this point—Oculus Rift, Samsung Gear VR, Sony’s Project Morpheus have all run the press gamut a few times over. But Fove wants to leapfrog the traditional players by coming to the starting line with something that none of those incumbents have (at least thus far): an eye-tracking system.

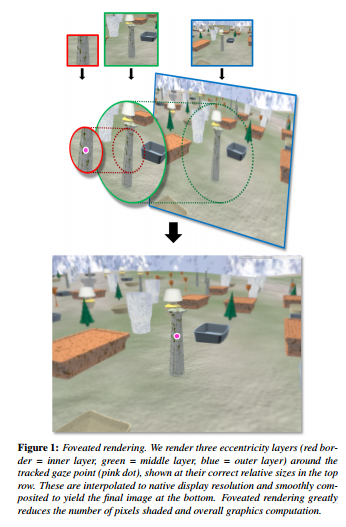

Fove says the eye-tracking system will eventually allow for foveated rendering—a cutting-edge way of reducing the processing demands of VR headsets by generating a high-resolution image only for the immediate area that a player is looking at, allowing peripheral areas to be rendered with less definition.Fove just met its Kickstarter goal of $250,000, which it will use to produce an SDK headset with a 5.8 inch display with 2560x1440 resolution, and a 0.8 pound weight. What sets it apart, though, are the infrared sensors that bounce IR light off the user's retinas, to measure the distance between the eyes and the direction they're each pointing. Kickstarter backers have been able to secure development headsets for between $300 and $400, and Fove aims to ship by Spring 2016. The development platform will integrate content from Unity, Unreal Engine, and eventually Cryengine.

Ars got a chance to try out a demo version of the headset, which was equipped with eye-tracking capabilities but not foveated rendering, which Fove says is still in development. The casing of the headset is sleek, and on my head it felt similar to an Oculus Rift DK2. It was a little heavy, but not to the point of discomfort. Once on, Fove’s team had me quickly calibrate the headset by looking at a succession of green dots projected at random points in front of me.

From there, the Unity-based demo was much like the one Ars experienced last year with German eye-tracking company SMI at the Augmented Reality Expo. The difference between SMI and Fove, however, is that SMI sells its eye-tracking tech to headset manufacturers and Fove wants to sell a headset with eye-tracking directly to the consumer.

I got to play a minute or two of a little first-person shooter where you aim at incoming triangle grenades with your eyes and then pull the trigger on a controller to explode them. The experience felt seamless and natural to me. I didn’t have to get used to the feel of a thumbstick to move around and there seemed to be only a little lag between looking at a target and being able to shoot at it.

For show, Fove’s team then turned off eye-tracking and head tracking—a quick 30 seconds of trying to play the same game in a more static world left me feeling nauseous and dizzy. (For comparison, Oculus Rift has had head position tracking since DK2, but eye-tracking is an added bonus in Fove.)

-

A side view of the FoveMegan Geuss

-

The body of the display seems to be a bit longer than that of its competitorsMegan Geuss

-

Yuka Kojima, the CEO and co-founder of Fove the company.

-

Kojima was busy setting up the demo area before the launch party kicked off.Megan Geuss

-

The inside of this Fove prototype had inverted cameras underneath the lenses to track eye movements.Megan Geuss

A bold plan

It’s an audacious thing to try to enter a hardware market with several heavy-hitting incumbents already on their way to producing a market-ready consumer version of a similar product.

Still, Fove’s founders, CEO Yuka Kojima and CTO Lochlainn Wilson, are no strangers to the video game industry. Kojima was a game producer at Sony Computer Entertainment in Japan before founding Fove. Wilson previously worked with an image processing startup in Australia. The two met at the annual Game Developers Conference in San Francisco and remained friends. When Kojima pitched her idea to Wilson, he joined up and later recruited two of his friends to help Fove build its product in Japan.

Since then, the company has had support and mentoring from Microsoft Ventures Accelerator London and it won a spot in the Rothenberg Ventures River VR Accelerator, which came with a $100,000 award to further their product. The company has also had support from the University of Tokyo and it says Toshiba and Samsung will be supplying components.

Obviously Fove’s value proposition lies not just in eye-tracking but in bringing foveated rendering to virtual reality game developers. That feature is still relatively new and untested in video games and virtual reality, but it has lots of potential to let game developers scale down the graphics processing power they need by overlapping different levels of resolution in a game world.

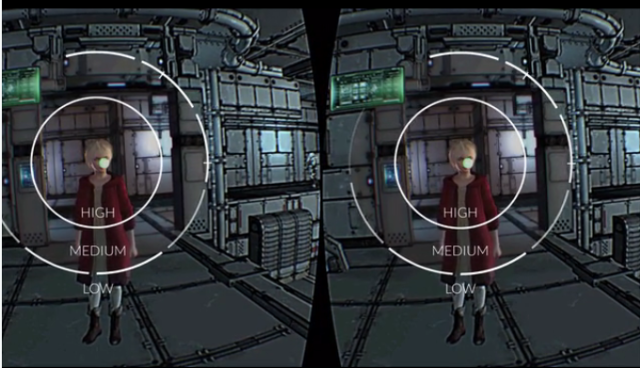

Fove’s press materials show a concept similar to the process laid out by Microsoft’s labs in a 2012 research paper (PDF). In this process, the highest resolution image will only span the small distance of the screen directly hitting the player’s fovea—usually only a couple of degrees. A concentric circle around that area has a lower resolution, and the periphery outside of that circle has a lower resolution still. Despite the degradation of the image as a whole, the human eye won’t know the difference as long as eye-tracking can keep the highest resolution area in front of your retina at all times.

There could be a catch to this attempt at reducing the technical requirements for VR hardware. Oliver Kreylos, a VR researcher at UC Davis, explained to Ars in an e-mail that foveated rendering needs to be very good or it could actually harm the user experience:

"The issue right now is that foveated rendering only pays off when screens have very high pixel counts, and eye tracking is highly accurate and has very low latency. It is very off-putting for the viewer if her eyes ever directly look at a portion of the screen that is rendered in reduced resolution. It's comparable to the oft decried problem of texture popping in 3D games where players suddenly find themselves looking closely at low-resolution fuzzy textures. If eye tracking is not good or fast enough, the full-resolution rendering area has to be expanded to cover all potential spots where the fovea might be in the next frame, and due to the significant overhead of foveated rendering, there might not be any performance gains (or even losses) as a result.

At this early stage, it’s unclear how easy that problem will be for Fove to solve, but experts in the field seem to think that working to create hardware, software, and a developer base that can make use of eye tracking is a step in the right direction.

Dr. Albert “Skip” Rizzo, a Director of Medical Virtual Reality at USC's Institute for Creative Technologies, recently attended a virtual reality conference where Fove made quite a showing. “Unfortunately there was a long line for the Fove, but I’ve heard from people that it’s pretty compelling,” he told Ars.

Since the '90s, Rizzo has been working to bring virtual reality to therapy, helping patients with PTSD and brain injuries by immersing them in therapeutic simulations. Fove has tested its products for similar use cases already: long before launching its Kickstarter, the company took its prototype into therapeutic situations, helping students at the University of Tsukuba's School for the Physically Challenged play the piano with their eyes, and allowing a paralyzed man to operate a robot through which he could interact with his family.

Rizzo says that even as an adamant supporter of head-mounted displays in therapeutic situations himself, he would want to see a clearly defined value proposition before predicting that Fove will be revolutionary in the field. "I think one has to be really clear about what eye-tracking may add to the mix here. My first question is do you need to have eye-tracking in a head mounted display to play the piano?” he asked, adding that eye tracking has been around for a long time and has helped patients who need it without the extra cost of a head mounted display. Still, "maybe there’s some value in having someone in a head mounted display where they’re blocking out the ambient light,” Rizzo suggested.

A personal project

Kojima told Ars that Fove’s eye-tracking will have multiple use cases, but that her personal goal in creating the headset was to make interactions with characters more realistic emotionally. Gamers like herself are "not satisfied with [the] current virtual reality system,” Kojima said, adding that eye contact “makes virtual reality more friendly.”

”I wanted to communicate with characters with non-verbal communication, I wanted to dive into the world with more sensitive contact,” Kojima told me at Fove's launch party last week. She turned to a demo of a game with a character looking at us. When Fove’s platform is complete, looking at the character's eyes will elicit a smile. By the same token, "if we look at her boob she will be angry, it’s more human,” Kojima laughed.

For Wilson, the project was a chance to make VR headsets more competitive in real-world gaming. "We don't believe that current virtual reality is competitive," Wilson said at Fove's launch party. "We would get our asses kicked if we were to play against someone with a keyboard and mouse." Eye-tracking, Wilson believes, makes response time in a head-mounted display faster and makes the player better.

Whatever the reason, over 650 other Kickstarter backers have decided that Fove's vision is the one they want to see in virtual reality next year. And VR is new enough that underdogs could become major players in that short amount of time. As Dr. Rizzo noted "there’s been an explosion of interest in head mounted displays. But three years ago, it was still a failed technology."

reader comments

28