Walking into the post-bankruptcy RadioShack feels like guest-starring in a burgeoning engineer's fever dream: aisle after aisle of tiny parts and power connectors and remote-control toys, DIY kits for building all manner of electronic games, stacks of the latest in headphones and speakers. Near the front door, there's an entire aisle of drones that can do barrel rolls over the shelving units. And you can play with anything you want.

Despite this, most of America believes RadioShack is gone. In February 2015, the company declared bankruptcy and announced that it was closing or selling all of its American stores. Late-night comedians pecked at the news like vultures on carrion. Jimmy Kimmel cracked that "people just aren't buying as many blank VHS tapes as they used to." John Oliver delivered a mock eulogy and produced a highlight reel of financial analysts laughing glibly at the company's demise.

But then, RadioShack didn't go away. Last March, Standard General, a hedge fund that specializes in distressed assets and had lent RadioShack hundreds of millions of dollars when it was in trouble previously, bought the company at a bankruptcy auction and promised to save thousands of jobs. The hedge fund created a new company, General Wireless, to buy the stores, mostly using the old RadioShack's debt as currency. They brought in Ron Garriques, a former Dell and Motorola executive, to be the new CEO. Then General Wireless partnered with Sprint to open more than 1,400 of the mobile carrier's stores inside remaining RadioShacks. Of the 4,000 RadioShack locations around before the bankruptcy, more than 1,700 never closed at all.

The company's #RadioShackisBack Twitter campaign is evidence of the labor required to remind the public of this fact. The campaign included an endorsement from Carlos Mencia and a video of comedian Orlando Jones shopping and singing "The Shack is Back!" In December, the company announced that rapper Nick Cannon, host of America's Got Talent, would become RadioShack's "chief creative officer."

"Every day I have to explain to somebody that, yes, we are still here," says Todd Schrader, RadioShack's vice president of stores, who has been with the company for seven years. "Yes, you can still get a lot of the same products you remember from your childhood, and a lot of cool new stuff, too."

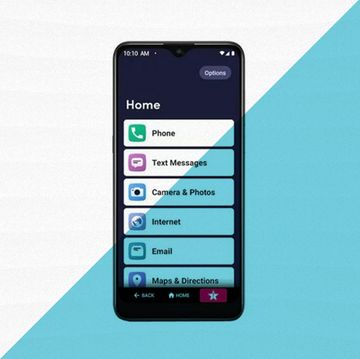

That's the idea with the RadioShack reboot: a return to the neighborhood electronics store—the parts and power, the pieces you need to fix something yourself—plus modern products the C-suite hopes will lock in customers for the future.

One of the revamped RadioShack stores on the outskirts of Fort Worth, Texas—where the company was headquartered for decades—has an aisle full of remote-control cars and boats that could have been featured in Saturday morning cartoon commercials 30 years ago. Gone are the TVs and laptops and kiosks from competing cell carriers that once turned the stores into run-down phone purveyors secretly wanting to be Best Buys. Now there are inexpensive soldering irons and a 3D-printing pen capable of "drawing" small plastic sculptures, and RadioShack-brand do-it-yourself starter kits to make water alarms or electronic clocks or a theremin. These kits, which have been around for years, were an important part of the new effort. Michael Tatelman, the new chief marketing officer, says it's an explicit attempt to court a new generation of makers and STEM students—the type who might be buying parts for decades to come.

In fact, restocking shelves was the first challenge the new RadioShack faced. Even stores that remained open through the bankruptcy sat barren for months. "It was a race to get inventory for the holidays," Tatelman says.

The bankruptcy rulings took nearly a year, and afterward the company's old credit lines were shot. The new RadioShack had to establish contacts all over the world, then contracts and credit lines. It had to work out the acquisition and the shipping and the pricing. A lot of the products bear names from the languishing RadioShack house brands, but the company had to find new places to make most of them. In November, when Amazon reported that a few retailers would be able to sell the Amazon Echo, RadioShack was on the list. (Best Buy wasn't.)

But when RadioShack announced (also in November) that its Black Friday sale would start two days early, the company again became late-night joke fodder. One of Saturday Night Live's "Weekend Update" anchors quipped: "You may know RadioShack from their slogan: Hey, didn't that used to be a RadioShack?"

Tatelman says it's been a journey. And that journey is far from over. In late January, Garriques resigned as CEO after less than a year on the job. The same month, mobile partner Sprint cut 2,500 jobs to make ends meet.

Still, as maker culture has surged in popularity among young adults who feel alienated from meaningful work, RadioShack is trying to become the phoenix of DIY consumer electronics—rising from its own ashes to encourage another generation to tinker. On top of all those drones and kits and cords and speakers, the new RadioShack carries something else: hope.