Premature Evaluation: Garbage Day

Throwaway

Each week Marsh Davies descends like a hungry urban gull upon the reeking heap of Early Access, hoping to yank free a tasty treat without choking on a crinkled Space Raiders packet. This week, he’s been stuck in Garbage Day, a game that is nominally about replaying the same looping time period, again and again, until you piece together the mystery and escape your temporal prison. In its current form, however, it’s no more than a colourful but cramped chaos sandbox, in which you can kill and maim cartoonish inhabitants of a highly-smashable town in the knowledge that any consequences will be reset as soon as the clock strikes midnight. But does its eternal present suggest a plan for reaching a less frivolous future?

According to Google Docs this is my 57th Premature Evaluation and - perhaps you should be sitting down - it’s going to be my last. There, there. If I’ve been able to discern any trend during the time I’ve been reviewing Early Access games, it’s that no one knows what they’re doing. Developers don’t know what they’re selling, customers don’t know what they’re buying, and I often don’t know what I’m reviewing - each week I play two or three games in the hope of finding one which is recognisable, even loosely, as a product against which even the vaguest expectations might be tentatively measured. The rejected games are frequently so amorphous in their unfinished (or, perhaps more accurately, unbegun) state that to review them at all would just be to bellow pointlessly into their cavernous absence of purpose. Sure, the boundaries between bare-bones alpha, fantasist Unity Asset Store piffle and outright scam are porous indeed, but I think most of the time developers of these games just don’t understand what it is reasonable to ask of a customer, what it is ethical to sell or what they need to show in order to convince people that their game can reach the future they have promised.

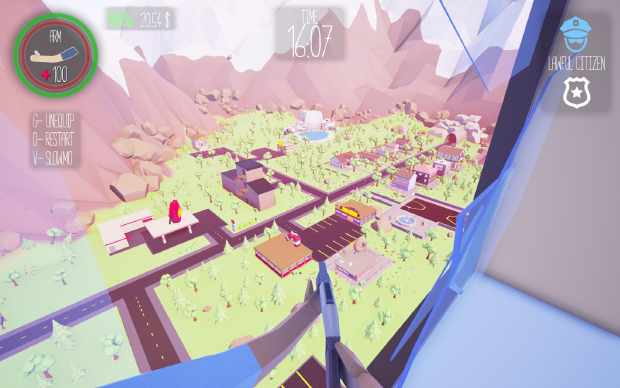

Garbage Day is therefore not only a frequently all-too-accurate alternate name for this column but paradigmatic of its problem. The central premise is currently entirely absent in any meaningful way from the game; the nuclear power plant accident which has apparently trapped you in time, Groundhog Day-style, is an event entirely confined to the Steam Store description. The power plant itself comprises a handful of empty rooms, and so it is with many of the buildings of this very small town, hemmed by unclimbable mountains. The occupants are similarly vacant, offering only the phrase “Blah blah blah” as they wander aimlessly back and forth. There are no clues to find in the sandbox mode that is currently the entirety of the game, and, moreover, no clue as to how such clues might be inclu(e)ded at a later date. Garbage Day in no way suggests how it will become more than it is, how it will seed its world with interactions that might unlock a complex plot.

This said, nothing about the game suggests it couldn’t meet such expectations, either. It is a fine, frivolous and passingly funny thing, and I’ve enjoyed all the minutes I’ve spent in it, even if I don’t feel compelled to spend many more. There is a naive slapstick to the low poly animations and a simple pleasure in the physics-enabled destruction of this chirpy, cartoon town. There’s a quality to the modelling, to the high-saturated blue-tinted palette, to the infuriatingly chipper music, to the way the moon rises right in the crevice of a mountain pass, which confirms that aesthetic choices have been made - and good ones, too - rather than emerging semi-accidentally from an assortment of Unity Asset Store parts. There are systems too, albeit disconnected from any real function: cash registers and bank vaults can be looted. Donuts can be ordered. Lawmen can be angered - although your wanted status can presently be erased by getting in or out of a car. It’s not the only bug: run over a shotty-toting sheriff and sometimes one of his identical mates will instantly explode in sympathy.

Waking at 7am, my first instinct is to trash my house, slinging its unanchored physics objects about and seeing what breaks. The game is a little inconsistent here: glass shatters and wooden doors can be obliterated, but a basketball will survive a point-blank shotgun blast. People don’t, though. Bits of them splurt off and roll about independently. Disappointingly, feeding them into a woodchipper produces no particular interaction. In fact, I think I’ve pretty much covered all the game’s interactions over this and the last paragraph. An array of weaponry sits in front of your house in the sandbox mode, and it does largely what you might expect. Melee weapons elicit an illicit giggle, but since cops will shoot you on sight after any act of violence, you might as well take a gun to even things up. As yet, climbing over the counter of a shop and emptying the register does not count as an infraction, and the citizens are remarkably tolerant of wanton property damage, too.

After a half an hour, I feel like I have exhausted most of the entertainment to be had ploughing through picket fences and gunning down donut retailers, and so I seek a way out. A mountain pass leads out into desert. Cacti disassemble most satisfactorily, I discover, though my car handles the terrain poorly, slipping, sliding and sometimes snagging on a vertex and flipping end-over-end. I make my way towards a lighthouse which I can see peeking over the dunes, but my car spasms itself into the water of the bay instead. Luckily it appears impossible to drown, and I am able to clamber slowly up a murky polygonal shelf to the surface. Dusk is setting now - I have scant few minutes of real time to reach the lighthouse before the day resets. I clamber up and around, but there is no way in.

Before I started doing this column, the excellent Chris Livingstone used to walk RPS’s Early Access beat, writing under the title “The Lighthouse Customer”. It was a phrase that I hadn’t heard before and I had to get Graham to explain it to me: like the canary in the coal mine, a lighthouse customer might warn others of dangers ahead. It seems fitting that, for my last review - of a game which is typical of Early Access in its embryonic formlessness and unknowable destiny - I discover the lighthouse doesn’t even have a door.

Garbage Day is available from Steam for £11, which is quite a lot for something this thin. I played version with the Build ID 940948 on 22/01/2016.

Thanks for reading the column over the last year and a bit! You all look very nice today.

![Furthermore, Cromwell - in this communication as in later ones - also makes plain that no civilians were to be harmed, nor their property ransacked, so long as they did not take up arms against him. There’s every reason to believe he was true to his word: only days before his first supposed massacre, Cromwell had hung a number of his own soldiers who had stolen a chicken from a local woman. He was quite clear in his declarations to his own highly-disciplined forces that the native populace was not to be molested, under pain of death, but instead generously compensated for whatever intrusion the New Model Army made upon them. As the campaign drew to a close, and victory became more certain, Cromwell proved lenient in both his terms of surrender and his offering of quarter. In some instances, he shows tremendous patience. Reading his letters is a delight - the exchange between Cromwell and the governor of Wexford is a masterclass in polite menace and dry wit. The governor, playing for time and overplaying his hand, asks for exceedingly unlikely terms - Cromwell is marvellously withering, dismissing the demand that all hostility end while negotiations are laboriously spun out: “I consider that your houses are better than our tents, so I shall not consent to that”. But Cromwell nonetheless does allow the governor many further chances, presumably again being reluctant to cause a further “effusion of blood”. After receiving an exasperating letter in which the governor relates an excuse for his various delays, Cromwell replies: “Sir, You might have spared your trouble in the account you gave me [...] These are your own concernments, and it behoves you to improve them.”](https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/images/16/jan/garbagedaype7.jpg)