The coming of the new year gives us an opportunity to both look back wistfully and look forward with hope. It also offers a chance to look back with anger and toward the new year with a sense of cynicism and schadenfreude. So, in the interest of curdling your eggnog a bit, we're dusting off Ars' tech company "Deathwatch" list to see which companies we've tracked in the past have managed to survive, which have slipped into various levels of oblivion, and which companies need to be added to the stack to replace those that have either emerged victorious or have fallen irrevocably into corporate limbo.

First, a clarification of our criteria for what places a company on Deathwatch. To be considered, companies need to have experienced at least one of the following issues:

- An extended period of lost market share in their particular category

- An extended period of financial losses or a pattern of annual losses

- Serious management problems that raise questions about the business model or long-term strategy of the company

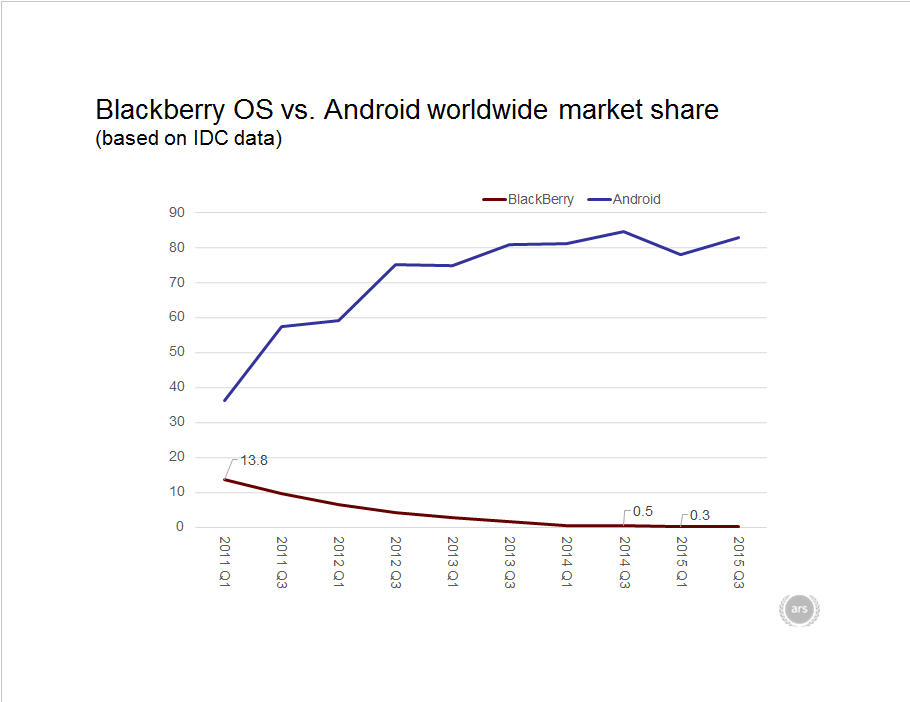

The Deathwatch took a holiday last New Year's, but our 2014 picks proved to be good for another 12 months of pain: RadioShack, BlackBerry, Zynga, HTC, and AMD. RadioShack, our most sickly suspect, restructured and then sold some of its stores to Sprint, closing the rest. While it still exists as a brand in some locations, the company has essentially ceased to exist. We rule that RadioShack has earned a toe-tag, while the others…well, they're largely in the same delicate condition they were in when we last did this list.

A target rich environment

That said, we only have one real returnee (well, two, sort of) from our end-of-2015 list—simply because there are other companies in play that are worth closer attention, and some of the companies still alive from our previous lists are effectively "undead"—greatly declined from their past position, but refusing to die outright because they've managed to downsize themselves into a survivable niche. Zynga and AMD fall largely into this categorization—their market shares have dwindled, but there's seemingly always someone who will play Farmville or who needs a cheap video card.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...