On Saturday, Nepal was shaken by a massive earthquake that registered a 7.8 on the Richter scale, causing widespread destruction in areas of dense population, and preventing aid workers from reaching more isolated villages in the mountainous regions. As of Tuesday, at least 5,000 people were dead and at least 10,000 were injured. Hundreds of thousands of people have been left homeless.

With any natural disaster, communication can often become a matter of life and death, and if phone lines are broken and cell towers crumble, relaying messages to the outside world and coordinating rescue efforts becomes that much more difficult. Add to that the fact that Nepal's government is woefully unprepared to handle such a humanitarian crisis, and chaos reigns.

Still, some volunteers are trying to impose order on the chaos. After the quake, which shook cities in India as well as Nepal, volunteer ham radio operators from India traveled to the region to relay messages from areas whose communications infrastructure is broken or overloaded. Ham radio, also called amateur radio, is a means of sending and receiving messages over a specific radio frequency, and it is often used in disaster situations because it operates well off the grid; transceivers can be powered by generators and set up just about anywhere.

Amateur radio has taken a back seat with hobbyists in recent decades as other means of wireless communication have become cheaper and easier for people to use (you don't need a special license from the FCC to operate a cell phone, although sometimes it seems like we'd be better for it if that were the rule). The decline in participation rates is unlikely to change substantially in the US, and the Times of India noted that awareness about ham radio is still low in India and nearby areas. Still, it has proven to be effective as a means of communication in Nepal in recent days.

Ars spoke to Jim Linton (whose call sign is VK3PC), the Chairman of the International Amateur Radio Union’s (IRAU) Region 3 Disaster Communications Committee, to get a sense of what kind of information ham radio operators are getting (Region 3 encompasses the vast Asia-Pacific area; Linton is based in Australia). Throughout the day, Linton received updates from Jayu Bhide (call sign VU2JAU), who is the National Coordinator for Disaster Communication for the Amateur Radio Society of India. Bhide was in frequent contact with people on the ground in the mountainous regions of Nepal that had been hit the hardest.

As of today, Bhide told Linton, rescue teams are still struggling to find missing people trapped in the ruins. In one case, a hotel housing four doctors was demolished during the quake. Only one of the doctors survived, and he stationed himself in a Red Cross facility across the street from the demolished hotel. "The flights from Kathmandu airport were delayed and people were stranded [in] several places,” Bhide added. "More than 17 Red Cross camps were set up.”

"The situation is still one of chaos,” Linton wrote to Ars this morning. "The Government of Nepal has asked all people to stay out of buildings due to them being unsafe.”

As of Tuesday morning, four amateur radio operators from India’s Gujarat region and four others from North Delhi have left to set up stations at critical places in Nepal. Three operators, including Bhide, said they are setting up High Frequency and Very High Frequency stations on the border between India and Nepal.

Amid the chaos, many Nepalese have struggled to get messages out to family members in other countries. The Los Angeles Times noted that the disaster has worsened the economic woes of an already poor country, which has long depended on foreign aid and remittances from family members working outside of Nepal. Bhide told Linton on Tuesday that much of his work had been to relay inquiries from family members abroad looking for news of their families. ”Many messages piled up to pass on to Nepal to find missing people,” Bhide reported.

”Many more HAMs were busy passing messages as well as forwarding them to relatives,” Linton wrote to Ars.

According to a January 2015 report from the Nepal Telecommunications Authority (PDF), only three percent of Nepal’s population relied on fixed telephony service like Public Switched Telephone Network (PTSN) or Wireless Local Loop (WLL) lines. By contrast, 86 percent of the population said they relied on mobile phone service to communicate. 39 percent of the population reported that they had Internet access. It is unclear how much of that communications infrastructure remains intact.

Bhide noted that “a request was also made to Ministry of Nepal to make mobile roaming free so that Indian mobiles as well as other mobiles can be used. It will reduce the load on wireless communication." On Tuesday, he added, "The mobile network and some telephones lines were restored along with power in some places.”

New tech, same problems

For areas where Internet is still accessible, some solutions to determine the safety of family members have surfaced. The International Red Cross quickly set up a website on which family members outside of the disaster area can report people for whom they are still searching. People who are safe in Nepal can report their safety on the site, called "Restoring Family Links," as well.

Facebook also dusted off its “Safety Check” feature, announced in October 2014, which asks people who are ostensibly in an affected area to confirm that they’re safe in the event of a natural disaster so that friends and family around the world won’t worry.

Still, this feature, while well-intentioned, is not a perfect solution to distributing information—issues about Internet access aside.

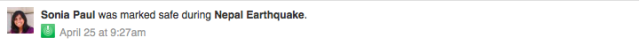

I personally noticed the feature on Sunday when I got a notice in my feed alerting me that Sonia Paul, a former colleague of mine who has been working in India for a couple of years, was “marked safe.” She had listed Lucknow, India—a city that did experience some destruction from the quake—as her location, but when I messaged her a day later, she said that she’d been working in Mumbai and never was in any danger.

Still, she got messages from concerned friends who assumed from the alert that she was in the thick of the disaster. Their concern, she said, was sweet but unnecessary—she had just clicked Facebook's automatic alert, and didn't realize it would cause such confusion. "It wasn't dire, just confusing," Paul said. "And that's the nature of our lives, that people move around a lot and are not always updating [Facebook]."

In contrast, she said, a friend of hers from Mumbai had gone trekking in the mountains where the earthquake was felt. But because he had listed his hometown as Mumbai, Paul said, "I didn't know if he was ok until I WhatsApped him.”

While Facebook's new feature is neat in theory, in practice, active confirmation of a person's well-being after a disaster is difficult and not always possible to reduce to an algorithm. Sometimes it takes the sweat of a handful of volunteers using decades-old tech.

reader comments

91