Eighteen months ago the cause of gender equality in UK universities got a welcome boost. Medical schools seeking biomedical research grants worth millions of pounds need not bother applying unless they had proven credentials in supporting women's career progression, the chief medical officer, Professor Dame Sally Davies made clear. For the first time, the pursuit of equality was explicitly linked to major funding streams.

Institutions could only expect to be shortlisted for the National Institute for Health Research cash, Davies said, if they had a silver award from Athena Swan – a scheme founded in 2005 that awards bronze, silver and gold charter marks based on universities' work tackling the under-representation of women in science. Since then applications for the awards have increased significantly.

But Athena Swan (Scientific Women's Academic Network) remains the only nationwide initiative aiming to improve women's representation at the highest levels of academia. It is currently focused solely on the sciences, and there is no such scheme for black and minority ethnic (BME) academics.

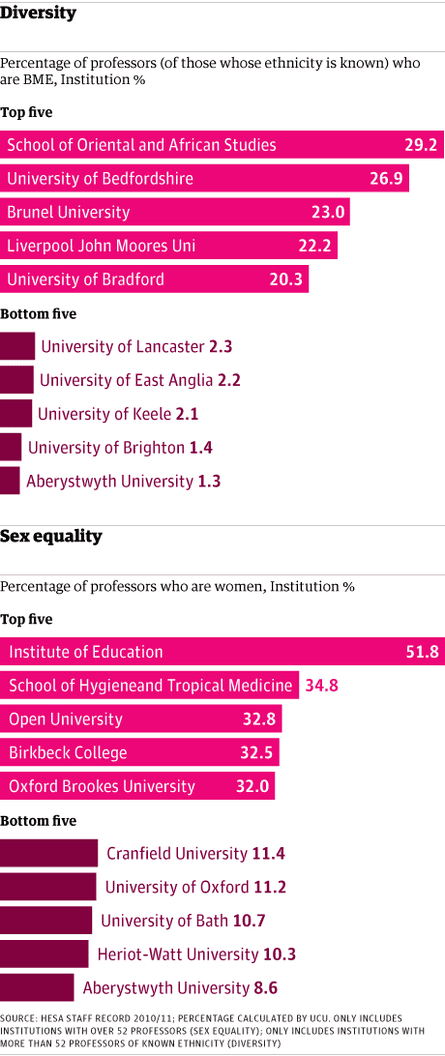

Given the findings of a new report by the University and College Union, that may come as a surprise. Figures released by the Higher Education Statistics Agency last week reveal that numbers of women and BME professors in our universities remain woefully low: just one in five professors are women (20.5%), despite the fact they make up almost half (47.3%) of the non-professorial academic workforce. Only one in 13 (7.7%) of professors are from BME backgrounds; BME academics fill 13.2% of other posts. The figures, for 2011-12, show only marginal increases on the previous year.

Using Freedom of Information requests, UCU looked into the applications process. Based on data from 21 institutions with some of the biggest gaps between representation at professor and other levels, it found that white applicants were three times more likely to secure a professorial role than BME ones. The data on women told a different story: they actually had a higher success rate than men, but weren't going for the jobs in the first place. Over four times as many men as women applied for professorial posts.

Why don't women apply for these positions? Many women feel the opportunity is not there once they have children. "I don't know if I could ever rack up enough papers to become a professor now," says Frances (not her real name), a senior lecturer in biosciences at a post-1992 university, who has three children. "I've spent too many years changing nappies. I work part-time and have had two nine-month maternity breaks. My department has been very supportive of my work to keep my research alive, but there are still only so many hours in the day. Most of my colleagues would probably do some of it at weekends or in the evenings. But I can't do that."

There is a familiar story, too, of women worrying that they don't have the necessary credentials to apply for jobs. "Women tend to undervalue what they can do," says Jenny Daisley, chief executive of the Springboard Consultancy, which runs development programmes for women at various levels in 40 universities.

What to make of the low success rate of BME academics? They made up 26.2% of applicants for professorial positions at the institutions studied, 18.6% of those shortlisted, and just 10.5% of those appointed. That gave them a success rate of 7%, against 21.1% for white applicants.

Some might argue that they must be applying for positions they are not qualified for. But that seems unlikely at such a high level, says Heidi Mirza, emeritus professor of equalities studies in education at the Institute of Education. She became one of the UK's first black female professors in the 1990s. "It has to be a discriminatory process," Mirza says. "Higher education is about peer review and has a fundamentally nepotistic way of operating. It's about networking and people supporting people they know who are like themselves, who they feel will mirror their own areas of interest. BME people often don't fit into that.

"Universities in the UK are still very much white, male institutions of privilege and self-reproduction."

Alison (not her real name), a respected senior academic, believes her exclusion from crucial informal networks is what has allowed white colleagues to pull ahead of her over the years. "It has taken me so much longer than my white peers to get to where I am now," she says. "You have to generate a large amount of grant income from external funders, but in order to do that you have to be invited on to research teams, and I feel I haven't had the same opportunities to be part of that as my white colleagues have.

"People tell you to go to conferences, join professional networks. But oftentimes to get to the next stage of becoming a professor it's more about informal networks – things like being invited to the dinner parties and other social gatherings. I feel that BME people just don't get those invitations – maybe because we're still seen as outsiders. As a result, you haven't got that level of support that white colleagues have. You really have to fight for yourself."

It seems incredible that universities, of all places, stuffed with the brightest and best, haven't cracked this problem. UCU wants institutions to introduce transparent professorial grading structures, as well as setting concrete targets for improvement, with specific time frames, and ensure progress is monitored at the highest levels. Too many of the stated equality schemes at institutions with above-average "representation gaps" lack measurable objectives, the report says.

Simonetta Manfredi, joint director of the Centre for Diversity Policy Research at Oxford Brookes, believes the chief medical officer's announcement provides a clue to one way forward. "The moment you link gender equality issues to funding, all universities will do it," she says. She's encouraged that the Equality Challenge Unit (ECU), which works on equality and diversity for staff and students, is piloting an Athena Swan-inspired scheme for women in arts, humanities and social sciences, with the University of Reading.

Last week, Research Councils UK said it expected institutions that receive its funding to provide evidence of the ways equality and diversity were managed; it stopped short of demanding formal accreditation, but warned that it would consider such measures if there was no improvement.

On the BME side, the ECU is focusing on unconscious bias, says head of policy Gary Loke – getting people to recognise it exists and then institute training to counter it. UCL and Leeds Metropolitan have been piloting such schemes, and the unit has commissioned an academic literature review on the subject to be published this year, to get people "to take it seriously". "We know that to persuade academics to think about these things they need to have empirical evidence," Loke says.

Karen Jochelson, director of economy and employment at the Equality and Human Rights Commission, says institutions that have identified that a particular group is not applying for jobs should consider positive action to widen the pool, such as the mentoring, networking or training schemes already in place at some places. "In sectors that work through personal networks, if people don't have the networks they won't necessarily understand what's needed at that next level," she says.

The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine has one of the highest rates of women in professorial roles, with 28 (33%) of its 85 posts held by women (in October 2012). It has a raft of policies in place that encourage women to build their careers at the school, from working from home and term-time contracts to transparent criteria for promotion. There must be at least one woman on boards making academic appointments, and half the current senior leadership team is female.

"I believe there's a snowball effect," says Laura Rodrigues, the school's equality and diversity lead, and a professor of infectious disease epidemiology. "The more the junior female staff and students see female scientists directing courses, leading seminars, being in positions of responsibility, the easier it is for them to see themselves in those positions. Being a senior scientist is no longer seen as a privilege reserved for white men." The fact the gender balance is better among professors promoted from within the school than appointed from outside suggests their policies are paying off.

For Jochelson, UCU's report shows "some very real problems". If institutions are serious about improving their record, the first step is collecting and analysing the data, she says.

But the quality of information provided in response to UCU's FOI requests varied hugely, according to the researchers, with a significant number of 35 institutions originally contacted unable to provide the data because they did not collate or retain it. The ethnicity of more than a third of professorial applicants, and even 9.1% of those actually appointed, was unknown.

Jochelson was surprised by the gaps in the data, saying they suggested some institutions might not be complying with the public sector equality duty (PSED), under which English universities are required by law to publish information about their employees and objectives for areas needing improvement. "It was quite shocking," says the report's author, Jane Thompson. "A lot of institutions said providing that information was voluntary, so it wasn't their fault if people didn't provide it. That's a cop-out."

But the coalition is reviewing the PSED as part of its "red tape challenge" to reduce bureaucracy, and that worries UCU's general secretary, Sally Hunt. "It's becoming even more difficult to believe that institutions left to their own devices will be committed to making the necessary changes," she says.

Alison still wants to become a professor. "I think it's important that people see a black woman achieving that," she says. "But it's very difficult, isolating and wearing. I didn't expect it to be like this: when you start out you think if you do everything you're supposed to do, your talent will be recognised and you'll progress. It's not like that."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion