Nasr City was once Egypt’s new capital, but things went wrong.

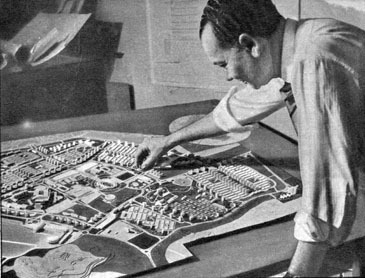

[Architect Sayed Karim pictured with his maquette of Madinet Nasr]

Mohamed Elshahed

One of Cairo’s least liked planned districts today, Madinet Nasr (Nasr City), was once intended to be Egypt’s new capital city. In fact it was billed in 1958 as “City of the Revolution” by the military regime that took power in 1952 and sought to establish its legitimacy through building and development projects across the country. In light of the Egyptian government’s recent announcement of its intentions to build a

new capital city, many of the statements used to promote the project

recall how in the late 1950s Madinet Nasr was presented to the public.

The

initial urban plan and architectural designs, mostly by architect and

planner Sayed Karim, were in tune with the times. The project’s brochure

contained English rather than Arabic text and was designed to attract

educated upper and middle class potential residents whom it assured that the new

city would be “planned according to the latest theories of city

planning.” An orthogonal plan composed of “super blocks” each containing apartments too expensive for the poor and largely catering to the

new middle class. The originally planned apartments ranged from

two-bedroom to four-bedroom duplexes. Each “super block” was to include

services and green spaces. A series of new administrative buildings were

planned (and some built) to house new ministries and to relocate others

from the downtown area. This was meant to be a modern city that reflects

the progress of the new regime.

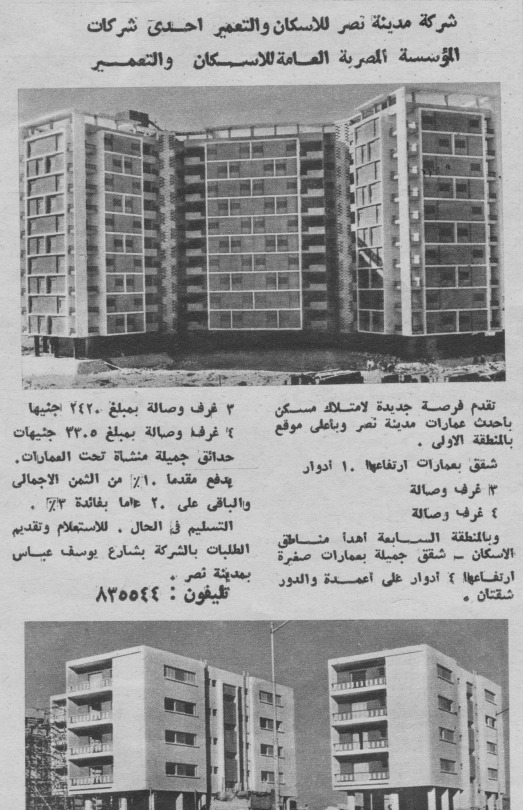

[Advert

for the new apartments in Madinet Nasr, 3 bedrooms+living room priced

2320 LE, 4 bedrooms+living room priced 3305 LE, to be paid %10

immediately and the rest over 20 years at a rate of %3 interest. An

average monthly salary at the time was around 17-20 LE]

But what went wrong? Today Madinet Nasr is chaotic, mismanaged (like the rest of Cairo and all of Egypt’s cities), congested with vehicular traffic in the absence of an effective public transport network, and the district’s density continues to escalate as low-rise residential buildings have long disappeared to give way to speculative apartment towers by developers. Furthermore, no one thinks of Madinet Nasr today as an independent city, its name has long become an anachronism referring to a brief moment in which the new city in the desert was meant to be that, a city. But its proximity to Cairo has made it today nothing more than an extension of the existing capital. So what is the story behind this former city of the future?

After 1953, the new

regime was struggling to tackle urban demands for better services and

more affordable housing. While popular (low-income) housing projects struggled to

meet demand and to be economically feasible, the state took on Madinet

Nasr, a large-scale urban development plan. In a company publication from the 1970s, the head of the

Nasr City Company Gamal Eddin Fahim stated that “our heroic

brethren, who struggled against occupation until our country was

cleansed from

it in 1956, have since then studied and planned for ways to raise our

people’s

standards of living and to fulfill the wishes of president Nasser and

Sadat

after him.” Nationalist politics were deployed to silence all voices in

favor of the visions of presidents, Nasser and Sadat after him, and the

city became a terrain for that singular voice of a president to showcase

his vision (or delusion).

According to Sayed Karim’s handwritten account of the founding of Madinet Nasr, in the early 1950s when he proposed his project to the municipality and various ministries, they refused to consider it because they saw his proposed expansion of Cairo as conflicting with the ideals of socialism. However, after a chance meeting with then officer Anwar Sadat, who was impressed by the architectural model of the city, Gamal Abdel Nasser gave a presidential order for its construction. Sayed Karim achieved his grandest commission by appealing directly to the highest echelons of political power. By the late 1950s Karim presented the plan not as a residential expansion of Cairo, as he originally envisioned it, but as a new capital with government offices, a stadium, and a convention center.

[A military parade with the first phase of Madinet Nasr 10-story apartment buildings seen in the background]

The design, implementation

and management of the new “city of the revolution” in 1950s Egypt was void of any

form of participation by the public or the future residents. It was a typical

high modernist development project that was built in the name of “the people”

as mere recipients of state-sanctioned modernity. The objectives of the newly

established Madinet Nasr Foundation (that later became the Nasr City Company) were as follows: to provide a new urban

model for desert expansion; to alleviate the housing crisis and population

density in central Cairo; to provide new governmental headquarters; to provide

housing for government workers; to provide serviced residential areas for

rental and ownership; to expand infrastructure into desert lands in order to be

sold “at a fair price” for private development; to connect the suburban

district of Heliopolis to the center of Cairo via new roads and public

transport options (at the time, only a single road linked Heliopolis to the

rest of Cairo).

The new city was positioned

east of the Abbasiya district, where military barracks were located, and

south

of the suburban enclave of Heliopolis. The total area of the project was

1200

square kilometers with the planned area as only phase one of a much

larger vision for expansion. Much of this was military-owned land.

Madinet Nasr was

ultimately a new district, rather than a new capital city in the fullest

sense but this status was ambiguous during the first decade and a half

after its announcement in 1958.

The development still relied on its connection to the existing historic

capital.

Although some governmental offices moved to Madinet Nasr, the major

symbols of

state power such as the parliament remained in the downtown area.

[Military officer giving a presentation about housing in the city of the future, Madinet Nasr]

Construction of the new district/city

was slow. In 1966, seven years after the presidential decree for the

establishment of Madinet Nasr, it was still discussed in the press as a plan

rather than as a reality. In addition to its slow

construction, families and workers were reluctant to move because of its

distance from the center of the city and the lack of effective transport

networks. Furthermore, the development’s lack of low-income housing forbid the majority

of those in need of housing from moving there.

By the mid-1970s, Madinet Nasr was still a work in progress in a perpetual state of construction and low

occupancy rates. It had failed to create the revolutionary urban setting it

promised, thus making visible the state’s inability to organize space as an

expression of its power. It also failed to respond to the pressing housing

crisis that had plagued Egyptian society for two decades.

With infitah

policies the state retreated from its position as the sole developer of

large-scale projects and opened the door for speculative developers to

enter the scene and build residential buildings that did not comply with

the original plan in hopes of maximizing profit. In the meantime the

state also retreated from its role as a manager of cities through its

institutions that could have allowed citizens to participate in their

everyday urban affairs. Governors continued to be appointed and

municipalities failed to carryout the most basic services from trash

collection to maintaining parks and trees.

Announcements and images of buildings and urban projects such as Madinet Nasr (or the new capital proposal now) aim to serve a legitimating function and to provide visible evidence of a developmental state responding to popular demands for change. However, without effective public institutions that value the well-being of all residents of the city such developments are doomed to failure as they already have in Egypt. I would argue that the failure of Madinet Nasr isn’t to be blamed only on the designs provided by architects and planners of the original vision. In my view, the failure of this past attempt at building a future city (and at managing the current one) is due to the reluctance of Egypt’s political power to allow for society any capacity to participate in controlling its urban present and envisioning and realizing its urban future.

*Much of this post is extracted from an upcoming chapter titled “Cities of Revolution: on the politics of participation and municipal management in Cairo“ appearing in Participation in Art and Architecture: Spaces of Participation and Occupation (2015), edited by Martino Stierli and Mechtild Widrich.

**A lengthier and more detailed discussion of Madinet Nasr appears in my dissertation “Revolutionary Modernism? Architecture and the Politics of Transition in Egypt, 1936-1967.”

169 notes

ayman-109 liked this

ayman-109 liked this alshareefsam liked this

fox911 liked this

fox911 liked this confahmal liked this

remusluqins liked this

remusluqins liked this  epharao reblogged this from cairobserver

epharao reblogged this from cairobserver  epharao liked this

epharao liked this kholodelkinanii-blog liked this

arquigraph liked this

arquigraph liked this  wizzatron reblogged this from cairobserver

wizzatron reblogged this from cairobserver boudicathebrave reblogged this from bloglikeanegyptian

territorealities reblogged this from cairobserver

sexybanano reblogged this from bloglikeanegyptian

sexybanano reblogged this from bloglikeanegyptian  ayarambles liked this

ayarambles liked this mybrainproblems reblogged this from abaegel

abaegel reblogged this from soso-surprise

soso-surprise reblogged this from bloglikeanegyptian

soso-surprise liked this

visirion reblogged this from bloglikeanegyptian

kshshu liked this

alexsankara liked this

tradramblings reblogged this from bloglikeanegyptian

countessdemontecristo liked this

visirion liked this

sokarplum reblogged this from bloglikeanegyptian

willempiresevercollapse liked this

nour-ishment liked this

nour-ishment liked this handaza reblogged this from cairobserver

handaza liked this

x-infatuation liked this

luscious-coptic-curls liked this

tomarza-blog liked this

zoghbyzovic liked this

zoghbyzovic reblogged this from cairobserver

eclipsedbythe-moon liked this

estimada-clienta-de-telmex liked this

estimada-clienta-de-telmex liked this mountpyre reblogged this from bloglikeanegyptian

infinite-scrolling reblogged this from cairobserver

bebowonder reblogged this from cairobserver

cairobserver posted this

- Show more notes