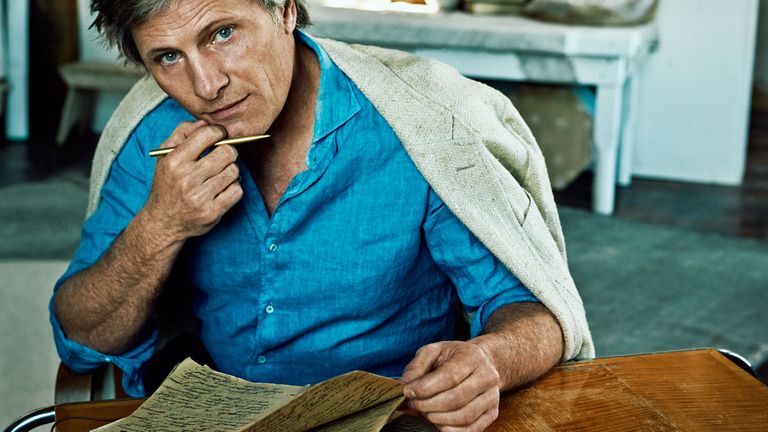

This summer, the quintessentially un-Hollywood Viggo Mortensen stars in a film about a father of six who rejects the world to raise his kids completely off the grid. How much does this character resemble the actor himself? Let's start with his flip phone.

Viggo Mortensen has come bearing pancake mix. We are curbside at the tiny airport in Syracuse, New York, on a truly dreary day (even by Syracuse standards), and within seconds of hopping into his rented Ford Fusion, I learn two things about him: He's the kind of guy who picks you up at the airport, and he's the kind of guy who brings presents. Pancake mix is a delicacy in upstate New York. "Do you like maple syrup?" Because he brought me some of that, too. He's prepared a gift bag.

"You can smoke in the car," Mortensen says, gesturing with his own smoldering American Spirit. "There's an ashtray." It's a cardboard cup from the airport Best Western, where he got his coffee this morning, that he has filled with an inch of water. For us.

Is he always this chivalrous?

He smiles. "I try."

Clooney, I tell him, probably never picks anyone up at airports.

He laughs. "He's probably a lot busier than I am."

We're here to talk about Mortensen's new movie, a subversive and surprising family drama called Captain Fantastic, and we're here here, in upstate New York, because Mortensen has taken some time off from his life in Madrid to care for his dying father. To see him to the end, same as he did for his mother, Grace, who passed away a year ago. Grace was a saint. His father, also named Viggo Peter Mortensen, not so much. But you do what you have to do. The old man is in Watertown, an hour and a half from the Syracuse airport, where Mortensen went to high school and where we are headed now.

And so we drive. Or, rather, he drives. For the next eight hours, for about 250 miles, up to and around Watertown, through the Adirondacks and not quite to Canada—though he does ask if I brought my passport—with periodic stops at diners and waterfalls, lakes and trout ponds, his mother's grave and finally his father's farmhouse. Viggo loves to drive. Sometimes he drives cross-country, just for the hell of it. And yet he has rented a Ford Fusion. "They always do this thing where they try to upgrade me to some fancy fucking car." But he doesn't want a fancy fucking car. At times, he spontaneously pulls over to the side of the road for a good five or ten minutes to finish a train of thought—about life or death or demons or fears or his favorite soccer team in Argentina, San Lorenzo. About the time in the wilds of New Zealand when he skinned, cooked, and ate his own roadkill. ("It was there.") About how much he loves the militant Chomskyite he plays in Captain Fantastic, a father of six who decides to raise his kids in the isolated wilderness of the Pacific Northwest. We could've gone straight to Watertown and stayed there, and we could've gotten there a hell of a lot faster, but Mortensen, his two hands resting gently on the bottom of the steering wheel, doesn't like to drive too fast. He doesn't want to miss a thing.

There are precisely two famous people ever to come out of Watertown. One of them is dead (the writer Frederick Exley), and the other one starred in the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Two and a half hours into our journey, Mortensen and I stop for coffee at a joint he likes because his mother used to go there as a teenager. The place is packed with a lunchtime crowd. We sit at the bar, and no one seems to recognize him, not even the pretty bartendress he chats up about Syracuse basketball. This is a remarkable feat for someone who looks like he does. But he just doesn't scream "I'm famous." Plus, he's dressed like everyone around him, in a plaid flannel shirt, generic jeans (they're not even Levi's), and old black sneakers he got in Denmark a couple decades ago. (Mortensen doesn't go in much for trappings. He has a flip phone!) Finally, as we're walking out the door, we hear: "Hey! Ya comin' to the reunion?"

Mortensen turns around. "Hey, Robin," he says to the waitress. They went to high school together. "How's your family?" She tells him where the class reunion is. It's in July, their fortieth. He just might do that.

I ask Robin what Mortensen was like in high school. "He was very quiet," she tells me. "He was a blond, beautiful, that's what he was."

Mortensen has never been like the other boys and girls. He is not in Us Weekly leaving Starbucks with his hand over his face. Not at Lake Como with George and Amal. When he must go on the red carpet, you will not find him in a Dior tuxedo. (He mostly wears vintage. Once, when asked whom he was wearing, Mortensen provided a name—Bambino Veira—and watched in bemusement as members of the Hollywood press dutifully wrote it down. Veira was a soccer player in Argentina.) He lives in Madrid, and he works when he wants to work, doing whatever he feels like doing. Once, it was erroneously reported (and repeated and repeated, which pissed him off, and he is not a guy who gets pissed off, except about the war in Iraq) that he was giving up acting because he said he wanted to take a break. He just wanted to take a break. Give him a fucking break.

Mortensen is fifty-seven and has been at this drill since 1982—choosing to become an actor at age twenty-three after watching too many movies and thinking, I can do that. His previous careers included driving a truck, delivering flowers, and loading ships in Denmark. For years he lived from gig to gig, check to check, mostly broke. It probably didn't help that, on a whim, he left L. A. and moved to Idaho. He supported his acting career for years by bartending and waiting tables. Then he got a couple breaks. Woody Allen cast him in The Purple Rose of Cairo, but his performance was left on the cutting-room floor. Ditto for Swing Shift, with Goldie Hawn. Finally, he was cast as a young Amish man in Witness with Harrison Ford, and the public got to lay its eyes on him for the first time. But that was 1985. It would be another sixteen years and at least as many (mostly obscure) roles before he would acquire true fame. He was offered the Lord of the Rings role only when another actor, Stuart Townsend, was dropped at the last minute, and he took it only because his then-eleven-year-old son, Henry, had read (and loved) the Tolkien trilogy and convinced him to do it. Box-office smashes, all three of them, and they made him hugely famous (for a time) and rich.

Then he did something truly bizarre by Hollywood standards. He had the world by the balls, with his pick of roles—big studio stuff, Clooney kind of stuff, paycheck stuff. He turned all of it down, choosing instead to do what he wanted to do, little of which was lucrative. "I mean, how much fucking money do you need?" he asks. He used some of his Lord of the Rings loot to start a publishing company—yes, a publishing company; it's called Perceval Press, after one of King Arthur's Knights of the Round Table—that would publish poets and other writers who might not otherwise get a book deal, and do so without having them "compromise." He could also afford to spend time on his other interests—writing poetry, taking photographs, painting.

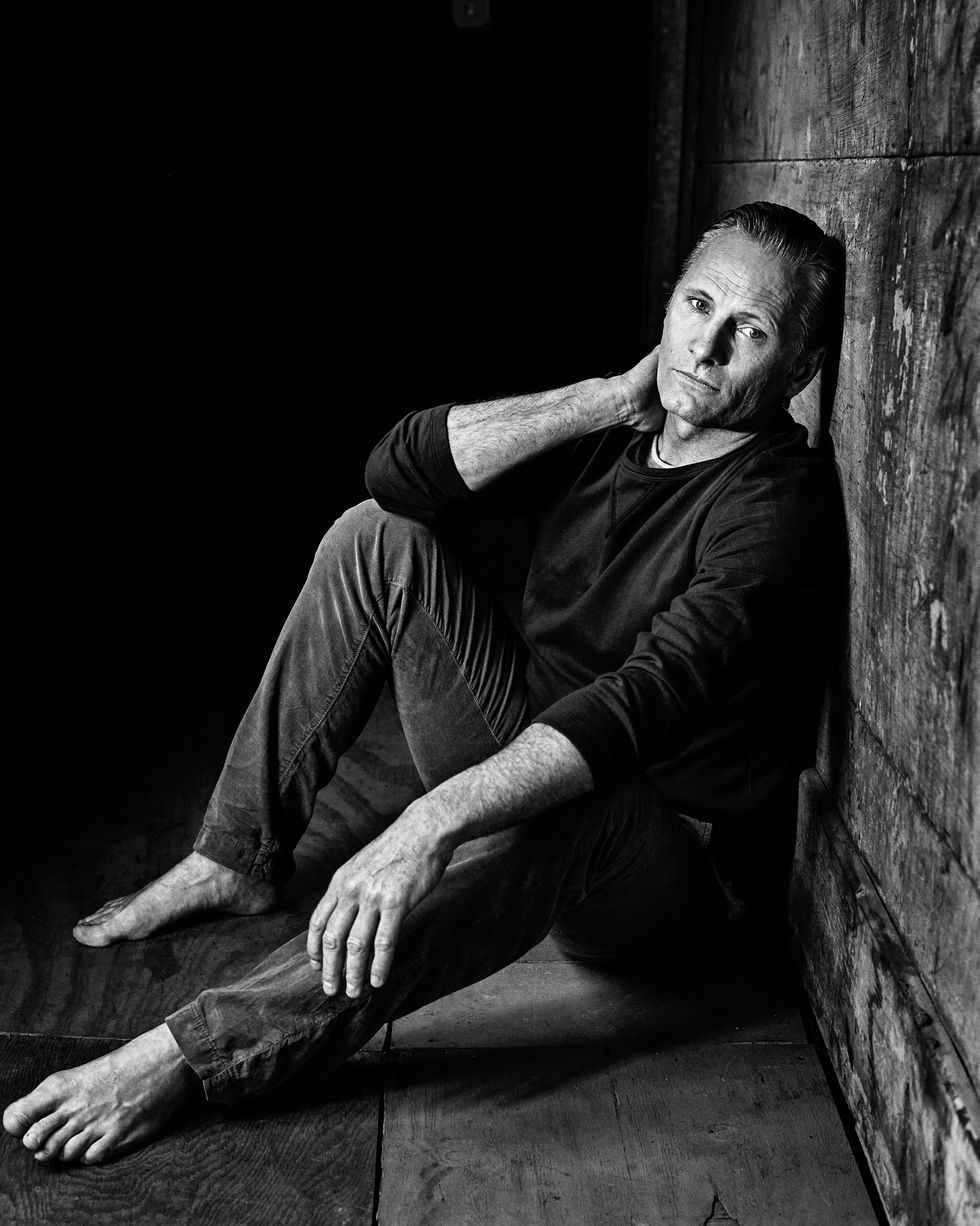

Still, it's not like he ever stopped acting. It's just that the roles he did take were mostly in indie films or David Cronenberg movies—dark, complicated, intellectual affairs that aren't on heavy rotation at the local multiplex. This led to spectacular performances in classics like A History of Violence, in which he plays a diner owner in the middle of nowhere who has (surprise!) a mysterious dark past, and Eastern Promises, a nasty piece of business about the Russian mob that got him his first and only Best Actor Oscar nomination and features a knife fight in the nude that few men can recall without wincing. (He lost to Daniel Day-Lewis, for There Will Be Blood.) And now there's Captain Fantastic, directed not by Cronenberg but by an actor-writer-director named Matt Ross, with Mortensen playing an endearing, passionate, complicated—okay, weird—father who tries to protect his kids from the pressures of a conformist, commodified society. There's lots of hunting and gore and kumbaya, and there's even a long, lingering scene of Mortensen once again in the altogether. He has never had a problem with letting it all hang out; like his ability to speak eight languages, he doesn't really get why people make such a big deal out of it. As his character says in the movie: "It's just a penis. Every man has one."

Four hours into our journey, we stop at a waterfall, and the sun is breaking through an overcast sky.

"It's just beautiful, isn't it?" he says.

His flip phone rings. It's his dad's nurse.

Today is only the second time since he flew back to the States from Europe several weeks ago—"when it seemed like only a matter of days" that his father had left to live—that he has left the house for more than a few hours. ("He's a tough son of a bitch," he says of his old man. "He rallied.") It took a while to find nurses he could trust, but he has hired one for today. She tells him there's a medical supply they've run out of that he needs to pick up. We leave the peaceful waterfall and drive into the strip-mall part of town, pulling into a dreary parking lot in Watertown.

"Is it okay if I go in by myself?" he asks. He doesn't need to say that it's a matter of dignity. His father is bedridden. Mortensen sleeps in the next room with a baby monitor on. He really doesn't need to say more.

He comes out of the store and discreetly loads his purchase into the trunk. And we head toward his dad's farm. It was his mother, he tells me, who was from Watertown. She met his father on a trip to Norway. "Little Viggo," as he was called—Europeans don't use junior—was born in New York City, the first of three sons. But when he was still a baby, his father—who was a farmer in Denmark—got a job with a company that sent him to Argentina to manage poultry farms. When Mortensen was eleven, his parents divorced and things got ugly. Grace took her three sons back to the U. S., to Watertown. Viggo the father went on to a string of wives and other women. Then he decided he would also move . . . right by Watertown. He said it reminded him of Denmark; Mortensen knows it had more to do with torturing his mother.

Now his father has dementia. His mother had dementia, too. Viggo is terrified that he will also get dementia one day. He's thinking of being tested for the gene. But then what? We are driving down a gorgeous country road with farms on both sides. Some of this land until recently belonged to his dad. But some months ago, "he decided he was broke. He's not. I said, 'You have all this land, sell it if you think you're broke.' And he did." Lots of farmland. "Then he calls me up one night and says, 'Someone's on my property, I'm gonna shoot them.' I said, 'You can't fucking shoot them, you don't own it anymore!' "

On the road, his phone rings again, this time with a call from his girlfriend in Spain. Mortensen was married once, to the punk-rock singer Exene Cervenka, the mother of his twenty-eight-year-old son, Henry Blake Mortensen, an actor and musician. Since 2009, he's been living in Madrid with the actress Ariadna Gil. Why Madrid? "Because I fell in love and she lived there." (After graduating from St. Lawrence University in 1980, not far from Watertown, he moved to Denmark and stayed there for a woman. He seems to do a lot for women, and his poetry, raw and intense, is filled with heartache. Has he had his heart broken? "Many, many times," he says, taking a long drag of his cigarette.)

We head down a gravel driveway to his dad's farmhouse. "Oh good," he says. He is happy that the daffodils he planted are already blooming. There is an old bathtub in the yard (they had to replace it with one they could lift his dad into). I wait in the car. Some fifteen minutes later, he comes back out. He looks a bit shaken. Apologizes for taking so long. Then says, "C'mere. Let me try to show you a little bit of my dad. He made this place to hang out with his friends." He takes me into a small red barn on the property and opens the squeaky door.

Oh, dear God.

There are animal pelts everywhere. Bears with heads on the floor. Moose on the walls. Horns everywhere. Dried elk poop.

"Yeah, this is his man cave," he says.

And we are suddenly both laughing hysterically, until it hurts.

We decide to grab a late lunch, pulling into a diner by Lake Ontario, where he orders a tuna-fish sandwich. On the way, he walks me through his "obsession" (his word) with death.

"I think about death all the time," he tells me as we both fire up another cigarette, him leaning over to light mine. "I mean, when I was a little kid, some of my first memories are waking up and going, 'Ugh, I'm gonna die.' " As a kid? "I guess living in the countryside, I might've learned about it earlier. That idea of mortality, you know? Once I realized that animals are gonna die, hence I'm going to die. . . ."

That had to be depressing. "No, not getting depressed, getting pissed off! Like, that's really bullshit. Like, whose idea was [dying]?" We laugh. He exhales. "I still think about death when I wake up. It's the first thing that enters my mind. But I think that's what makes me want to try things, you know? Whether it's writing or painting or whatever. To record what's happening as it goes. It goes quick." That helps explain the well-worn leather-bound journal he carries with him everywhere. He wants to "record life."

In the diner, he asks for the time. (He doesn't wear a watch.) "I better get you back," he says. Ninety minutes later, we pull up to the departure gates at the airport. I begin to say goodbye. But no, Mortensen is coming in with me. Way earlier in the day, in our first ten minutes together, I mentioned that I forgot my driver's license and that some drama ensued at LaGuardia Airport. He's coming in with me to make sure I get on my flight. He thinks maybe he'll know one of the TSA agents, but when we get to security, he knows no one. Nor do they know him.

The TSA cop wants to know what I was doing in Syracuse for just eight hours. She thinks I'm a drug dealer. At this, Viggo starts to laugh. I tell her I'm a writer and had to interview someone. "Huh." She looks Mortensen up and down. "Are you famous or something?"

On the other side of the security rope, Mortensen couldn't be happier.