How Doctors Think: Suicide Prevention

Second in a Series about "How Doctors Think"*

By Lloyd I. Sederer, MD and Jay Carruthers, MD**

About 10 years ago, one of us (LIS), as mental health commissioner of NYC, was providing budget testimony before a committee of the City Council. One of the City Councilors asked what my agency was doing to reduce suicide attempts and deaths in the City.

In addition to funding Lifenet (now a national crisis line), I spoke about my agency beginning an audacious initiative to implement depression screening and management in all primary care practices in the city.

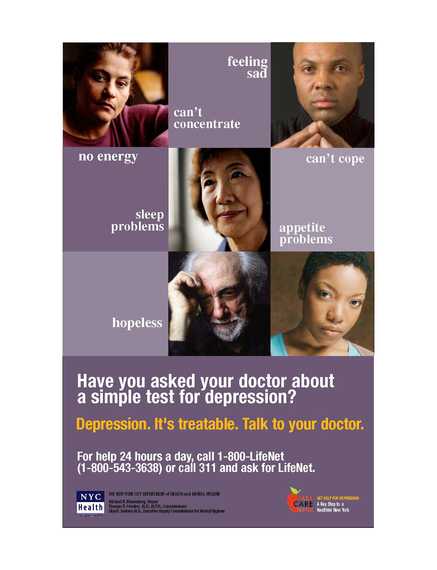

We knew clinical depression was present in a vast percentage of people who make serious suicide attempts. By detecting and effectively treating depression in primary care settings, where most people appeared -- especially seniors -- in the days and weeks before an attempt, we envisioned reducing suicide attempts among residents of NYC by treating the mental disorder that was instrumental to prompting people to this form of self-destruction. We had launched a depression treatment campaign; we even had a poster and media campaign at doctors' offices, on buses and the subway and at ATMs!

However, that was what we knew then. Since then we have learned more about how best to reduce suicidal behavior. While a social media and public education campaign about depression was (still is) needed and detecting and effectively treating depression in primary care (and other) settings was (still is) necessary those did not translate into immediate reductions in suicidal behavior.

We have since learned that to reduce suicidal behaviors we will need to separate intervening in the acute, transitory suicidal state from other efforts to treat any accompanying mental or addictive disorder, including depression. In other words, detection and treatment of an underlying mental health condition is still necessary but it is not sufficient if we are going to reduce suicides in NYS (or elsewhere).

Doctors, mental health clinicians, and community health workers now must learn to think (actually practice, not just think) differently to save the lives of suicidal people. First, they need to ask (as they always have), in ways that do not rush or shame, whether someone is or has reached the point where living has become a form of intolerable suffering. After asking, today's clinicians will principally need to learn to do three things for those at risk:

1.Establish a "Safety Plan", a preplanned way to get support and reduce the impulse to act (an educational video on Safety Plans is available here).

2.Maintain phone or in person contact (called a "Warm Handoff") in the days following a suicide attempt, an emergency room visit, or a psychiatric or addiction hospital stay.

3.Reduce access to deadly means of self-destruction, especially guns.

Each of these is described in more detail below. The need to treat any active mental and substance use disorder does not go away -- but that will take time. A person has to be helped to stay alive until the treatment works and any deadly impulses abate.

A Safety Plan is a prioritized list of supports and coping strategies to be used when suicidal urges arise. A trained clinician works collaboratively with the patient to construct an individualized safety plan. Core to this effort is the view that the suicidal individual is the expert on his or her life; the clinician is the expert on interventions that can help. Together they craft a plan that is then practiced and refined over the course of treatment, in which specific self-management skills and action steps to obtain support are employed during times of distress.

It has been identified that the period immediately following discharge from an inpatient psychiatric unit or Emergency Room as high risk for suicidal individuals (especially within the first 30 days). Clinicians now need to carefully attend to these transitions in care and ensure that services bridge the gap between the hospital/ER and the patient's engagement in outpatient services. One such approach is called "structured follow-up" where the hospital team develops a Safety Plan with the patient just prior to discharge. Equipped with a copy of the hospital safety plan, a trained staff person calls the patient within 24 hours of discharge. In a series of brief calls -- often lasting fewer than 15 minutes -- the clinician does a quick mood and safety check, reviews the safety plan (refining it if needed), and problem solves around any barriers that might limit additional treatment and social supports. Calls can continue until all agree that what is needed for safety is in place.

Finally, we know the vast majority of individuals contemplating suicide experience some measure of ambivalence about taking their life. For many, the time from first thinking about ending their life to the time of attempting suicide is often minutes to a few hours. These brief, but transient, moments of acute suicidality can come on powerfully and suddenly -- and exceed a person's capacity to use a Safety Plan or seek help. In those instances, what is critical is whether a person has immediate access to lethal means of dying, especially firearms. Guns account for over 50 percent of all suicides in the U.S each year and are lethal in over 85 percent of cases. Thus, doctors now need to think and ask about access to deadly means of suicide, especially weapons. Taking steps to "suicide-proof" a home with safe storage of firearms, using gun locks, and reducing access to dangerous medications can prevent a brief period of overwhelming distress from turning into the tragedy of a family suicide.

Doctors and other health and mental health clinicians are learning to think differently about suicidality, and thereby reduce its grave consequences. They need to learn, as we have and you will as well if you have a loved one with a mental illness or addiction, to uncouple treating the disease state from intervening to keep someone alive. The three practical approaches described here work. When they become broadly adopted and consistently used in clinical care many lives will be saved.

---------

*The first in this series was: How Doctors Think: Addiction, Neuroscience and Your Treatment Plan, The Huffington Post, June 29, 2015.

** Dr. Carruthers directs the Suicide Prevention Office at the NYS Office of Mental Health and is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Albany Medical College in Albany, NY.

......................

Dr. Sederer's book for families who have a member with a mental illness is The Family Guide to Mental Health Care (Foreword by Glenn Close) -- is now available in paperback. He takes no support from any pharmaceutical or device company.

His website is http://www.askdrlloyd.com

__________________________

Need help? In the U.S., call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.