You don’t have to get many belts in taekwondo to realise the most intense fighting is actually going on between men in blazers. Back in the 1980s there were only two rival international federations governing the Korean martial art. Today, as with Trotskyism, even more splinter groups have proliferated. Meanwhile in boxing there are at least four separate organisations that can dub you “world champion”.

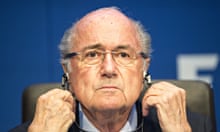

So Fifa, before it descended into crisis, was that rare thing: a world sporting body with no refuseniks. Thanks to the largesse of its executive – recycling sponsorship money to small national associations that would remain loyal to the centre – it became the perfect global monopoly. It was, until last Wednesday, seemingly above national jurisdiction. Though headquartered in Geneva, Fifa – like globalisation itself – seemed really to be domiciled in a first-class cabin, 32,000ft above the earth.

Any mere government uppity enough to suggest it was corrupt, or overpowerful, could have its representatives threatened with expulsion. But it turns out Fifa is, after all, subject to national laws and it is possible – whatever the outcome of individual corruption allegations – that once applied, these laws will lead to its breakup. And if it falls apart, it will do so along the same faultlines that are tearing the global political order apart.

Russia’s immediate condemnation of the FBI’s swoop on Fifa set the tone. Perhaps, mused Vladimir Putin’s many fans on Twitter, the Russian secret police should now investigate Nato. When it came to the vote, on Friday, over Sepp Blatter’s leadership, it was done as a blatant piece of east-west geopolitics, with the emerging world lined up, much as it was in the cold war, between the different sides.

But Fifa is only the latest episode in a growing mismatch between globalisation as an ideology and geopolitical breakup as fact. The Eurovision Song Contest, for example, has for half a decade been a politicised farce. It is less a musical competition, more a proxy ideological war in which the nations of eastern Europe express loyalty or loathing to Putin using breast implants and whitened teeth as signifiers.

When it comes to the internet, it is increasingly Balkanised. One-fifth of humanity – China – is not allowed search terms that coincide with such sensitive political events as the ruling party congress. Turkey, during the political unrest of the past two years, has regularly switched off parts of a global system nominally owned and controlled by American and British multinationals. Brazil, in its desire to avoid surveillance by the US-UK intelligence system, is laying private fibre-optic cables to Portugal and Angola.

And then there is truth itself: as purveyed through the English language news channels aligned to various sub-global powers, it too is fragmenting. No sooner had al–Jazeera begun to lay off journalists in Doha than an English language channel formed at the behest of Turkey’s president Erdogan scooped them up. To achieve their aims, which is to make all truth look like propaganda, the TV channels aligned to various despots do not have to be credible. They simply have to make every fact contestable on social media.

Those of us who watched the dazzling rise of globalisation in the 1990s always assumed that – because it was an economic system – if it ever fell apart it would be with economics first, politics second and the globalist ideology a long time after. That has proved completely wrong. Patterns of trade certainly shifted after the traumatic highpoint of the global era, the post-Lehman Brothers crisis. But the world market has not itself, yet, fragmented. Instead it is at the level of sport, music, news, censorship and surveillance that the world system is falling apart.

Fifa, for all its problems, is a good example of why global systems are worth pursuing in economics. They formalise rivalry, set explicit rules, contain conflict by making the absence of it a positive sum game. But the problem is, over time, their original structure becomes mismatched with the underlying geopolitics, which shift.

At the start of the global era it was assumed that, given time, most countries would become less corrupt and more democratic, because the market can only function under the rule of law. Global consumer brands emerged, always premised on the assumption that even if they did business with crooks, they themselves were a civilising force against crookedness. But the Fifa debacle only dramatises a general problem now for global capital. The world’s elites are fairly happy with corruption, and prepared to see it rise – alongside the rise in censorship and TV propaganda channels, and militarised riot policing.

The soccer billboards, which once only advertised clean, western consumer brands, are now for sale to companies like Gazprom, so openly aligned with dictators that they were sanctioned by the US. Globalisation did not lead to most of the world becoming like the west, but to the west’s ideals – democracy, transparency and the rule of law – becoming ever more beleaguered.

It is likely now that two or three of the giant brands reliant on global football will, at some point, try to re-form Fifa as a private entity – much as happened when the English Premier League seceded from the FA. If so, what emerges will be cleaner, more oriented to the corporate values of the US than to those of Azerbaijan, and quite possibly a bigger money-spinner. But it is unlikely to be truly global. In that, Fifa is a parable about the future of capitalism.

Paul Mason is economics editor of Channel 4 News. Follow him @paulmasonnews.