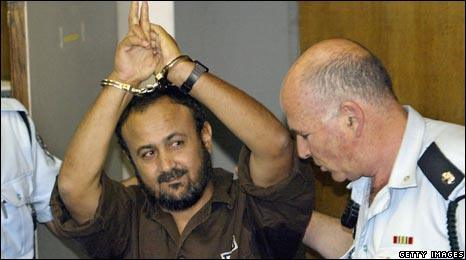

Profile: Marwan Barghouti

- Published

Marwan Barghouti was not well known among Palestinians until he came to prominence as a leader of the second Intifada.

But it was his arrest by Israel in 2002 and conviction on five counts of murder two years later that turned his into a household name.

Barghouti enjoys widespread respect and support among all Palestinian factions and, despite currently being in an Israeli prison, is now considered a favourite to succeed to Mahmoud Abbas as President of the Palestinian Authority.

Such an outcome would depend on him being freed in a major prisoner exchange, possibly in return for the Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, who has been held in Gaza since June 2006.

'Young guard'

Born in 1958 in the village of Kobar, near the city of Ramallah, Barghouti was nearly nine years old when Israel occupied the West Bank and East Jerusalem during the 1967 Middle East war.

At the age of 15, he became active in the Fatah movement of the late Yasser Arafat.

In 1978, he was arrested and imprisoned by Israel for more than four years on charges of being a member of an armed Palestinian group.

Barghouti completed his secondary education and learned Hebrew while in jail, and after his release in 1983, began a degree at Birzeit University.

It took another 11 years to finish his studies, however, as he remained politically active and became a leading member of Fatah's "young guard", who came to prominence while the movement's established figures, including Arafat and Mr Abbas, were exiled in Lebanon and Tunisia.

Then, in 1987, Palestinians broke out in revolt against Israeli occupation, in what became known as the first Intifada, or uprising. Barghouti emerged as a leader in the West Bank, and was later deported to Jordan.

Disillusioned

He returned in 1994 following the Oslo peace accords. He strongly supported the peace process, but was sceptical about Israel's commitment to successive land-for-peace deals.

In 1996, he was elected to the Palestinian Authority's new parliament, the Palestinian Legislative Council, with overwhelming support.

He then launched a campaign against human rights abuses by Arafat's own security services and corruption among his officials, further raising his profile.

At the same time, Barghouti established close contacts with several Israeli politicians and members of the country's peace movement.

But by the summer of 2000, especially after the collapse of the Camp David summit, he had become disillusioned. He predicted that the "next Intifada" would mix popular protests with "new forms of military struggle".

The second Intifada broke out that September after a visit by Ariel Sharon, then the leader of Israel's opposition, to the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem, which houses the al-Aqsa mosque, sparked Palestinian anger.

Now leader of leader of Fatah in the West Bank and chief of its armed wing, the Tanzim, Barghouti led marches to Israeli checkpoints, where riots broke out against Israeli soldiers.

He also spurred on Palestinians in speeches, condoning the use of force to expel Israel from the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

"While I, and the Fatah movement to which I belong, strongly oppose attacks and the targeting of civilians inside Israel, our future neighbour, I reserve the right to protect myself, to resist the Israeli occupation of my country and to fight for my freedom," he wrote in the Washington Post newspaper in 2002.

"I still seek peaceful coexistence between the equal and independent countries of Israel and Palestine based on full withdrawal from Palestinian territories occupied in 1967," he added.

Arrest

The second intifada saw a number of armed groups associated with Fatah and the Tanzim emerge, most notably the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades, which carried out numerous attacks on Israeli soldiers and settlers in the West Bank and Gaza, and suicide bombings targeting civilians inside Israel.

The Israeli authorities accused Barghouti of having founded the Brigades, which he denied, though he hailed some of the group's operations.

Having survived an Israeli assassination attempt in 2001, when his bodyguard's car was hit by a missile, the Brigade possibly sealed Mr Barghouti's fate when it issued a statement in 2002 claiming him as its leader.

Barghouti was arrested by Israeli troops in Ramallah that April and first appeared in an Israeli court the following August - charged with the killing of 26 people and belonging to a terrorist organisation.

Throughout his trial, he refused to recognise the legitimacy of the Israeli court. His lawyers insisted he was only a political leader, and sought to turn the process into a trial of Israel and its occupation of Palestinian territory.

In 2004, Barghouti was convicted on five counts of murder for the deaths of four Israelis and a Greek monk, as well as attempted murder, conspiracy to murder, and membership of a terrorist organisation.

The court found there was insufficient evidence connecting him to the 21 other deaths on the original indictment.

Continued role

But even from his prison cell, Barghouti has remained an important Palestinian political figure.

He helped negotiate, using his mobile phone, a unilateral truce declared by the main Palestinian militant groups in June 2003.

That ceasefire collapsed two months later, following a Palestinian suicide bombing and an Israeli air strike that killed a Hamas political leader.

Barghouti also drafted the 2006 Prisoners' Document, in which jailed leaders of all major factions called for a Palestinian state to be established within pre-1967 borders and the right of return for all Palestinian refugees.

He also helped forge the Mecca Agreement, which attempted to bring about a national unity government for the Palestinians in 2007.

And this August, Barghouti was elected to Fatah's Central Committee, along with other members of the "young guard" - now in their 40s and 50s - including Gaza strongman Mohammed Dahlan and Jibril Rajoub, a former Arafat aide.

The prospect of Barghouti's release has divided Israel, with some cabinet ministers arguing that as a reformist who could unite the rival Palestinian factions, he offers the best prospect for peace should Mr Abbas step down, and others saying someone convicted of five murders should never walk free.