A young woman walked into a Family Dollar store in Cleveland, exhausted, sweaty and desperate. Michelle Knight was 21 years old, and she'd spent the past few hours searching for the location of a crucial meeting. The appointment, with social services, was to discuss how she might regain custody of her 2-year-old son, who'd been placed in foster care a few months earlier after her mother's boyfriend got drunk and, Knight says, became abusive and broke the boy's leg.

It was August 2002—years before smartphones and Google Maps—and after nearly four hours of wrong turns, Knight spotted the Family Dollar store. She bought a soda and started asking people for directions. A woman in the soda aisle couldn't help. The cashier couldn't either. Knight was about to walk out when she heard a male voice: "I know exactly where that is." She looked up and saw a man with thick, messy hair and a potbelly, dressed in black jeans and a stained flannel shirt.

"Oh my gosh, you're Emily's dad!" Knight said. Standing before her was Ariel Castro, the father of a girl she knew from the neighborhood. While Knight had never met him, she'd seen photos of him on Emily's cell and overheard her talking to him on the phone.

Castro smiled. "If you give me a second here, maybe I can show you how to get there," he said softly. "Want me to give you a ride?"

She gratefully followed him out to his car.

Castro's orange Chevy was littered with Big Mac wrappers and Chinese food containers. "Wow, you must live in this place," Knight said, as recounted in her memoir, Finding Me: A Decade of Darkness, a Life Reclaimed. He laughed. Instead of driving straight to the social services meeting, he told her he had to make a quick stop at his house first. They started talking about Knight's son, Joey, and then Castro mentioned that his dog had just had puppies. By the time he pulled up to his house on Seymour Avenue, just a few blocks from where Knight lived, he'd convinced her to take one home for Joey.

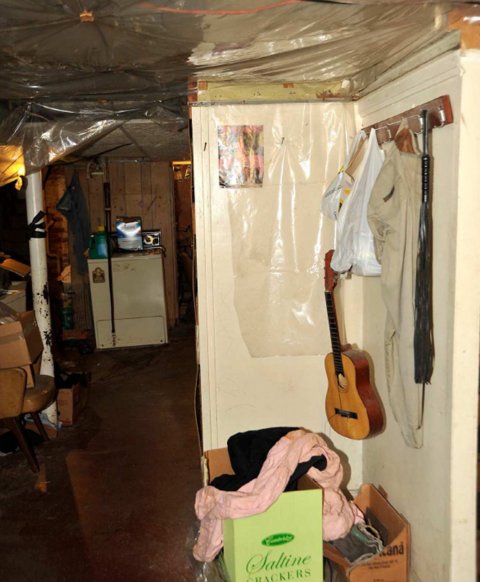

A tall chain-link fence surrounded the dilapidated, multi-story home, and trash was strewn across the lawn. Castro drove down the driveway, got out of the car and secured a large padlock on the gate. That puzzled Knight. Weren't they only going to be there for a few minutes? Castro said something about not wanting his truck to get stolen, then helped her out of the car. She saw an old man standing in the yard next door, so she waved. He waved back. Then she followed Castro inside.

The thick air smelled like stale beer, urine and rotten black beans, and many of the windows were boarded up. Knight couldn't believe Emily spent time here. "She's right downstairs, putting some laundry in the machine," Castro said. "Why don't you come with me upstairs so you can go ahead and pick out a puppy?" Knight hesitated. She didn't hear any puppies. She didn't hear Emily either. But Castro had an answer for everything: The puppies were sleeping, and Emily would be up any moment. He pointed to the staircase, and Knight started climbing.

On the second-floor landing, he directed her to a small bedroom with pink walls. "They're under there," he said, pointing to the dresser. Knight took another step forward and—BAM!—Castro slammed the door shut behind them. He then slapped one hand over her mouth and nose and the other against her head, and pushed her to the ground. Knight started shaking. She couldn't scream. All she could do was stare at the two metal poles on either side of the room, and the taut wire running between them. Castro tied an orange extension cord around her ankles and wrists, yanked her limbs together behind her back, then wrapped the cord around her neck. "You're only gonna be here for a little while. I'm not gonna keep you that long," she remembers him saying as he unzipped his pants and masturbated until he ejaculated on her.

Castro then sat on a stool, breathing heavily. "Now I need you to be still so I can put you up on these poles," he said, shoving Knight onto her stomach. He tied a second extension cord to the one around her limbs and neck, then attached it to the wire hanging between the poles. Suddenly, Knight felt herself being roughly hoisted into the air. Her entire body dangled, face down, in a plank position about a foot above the floor, neck cocked, back arched slightly, hands and feet bound behind her. Castro stuffed a smelly sock in Knight's mouth, covered it with duct tape, blasted the radio and walked out. She heard the door slam shut and his feet pounding down the stairs. Then, nothing.

"The first thing that came to my head was, Holy shit, I'm gonna die here," Knight says. "I'm not gonna be able to hold my son in my hands. I'm not gonna be able to say I love him. I'm gonna miss every moment of his life."

Knight choked back those same fears, day after day, for the next 11 years.

Sadism Sells

Knight closes her eyes for a moment and tilts her head up toward the sun. When she opens them, she says, "Watching the clouds go by is so beautiful!" I follow her gaze and notice that the pale-blue sky is studded with delicate white wisps. It dawns on me that someone who was held captive for over a decade—raped, beaten, starved, chained and rarely let outside—would of course want to stop and watch the clouds float by.

We're sitting outside a restaurant in downtown Cleveland. Knight, who's 34 now, wears a magenta and black-leopard-print blouse, dark jeans and pink lipstick. She gently pats her short blond hair and points to a meaty green animal tattooed around her right wrist. "This is a protection dragon," she says. She raises her left sleeve and drops her shoulder, revealing five large roses cascading down her arm, each one covered in drops of blood. "Every rose is for every abortion that I had in the house."

It's mid-June, just 10 days after the two-year anniversary of her rescue from Castro's house. Since then, Knight legally changed her name to Lillian Rose Lee and has become an advocate for victims of abuse and violence. She's also covered her body with tattoos. On her right shoulder, there is a brown teddy bear decorated with red hearts, a design she drew during captivity. On her chest, a baby and the phrase "Too beautiful for this Earth." On her right calf, there's a large face, part skeleton and part flesh. "This tattoo represents my life from the past and my life in the future. It says, 'My heart is not chained to my situation.'" Knight often talks in quotes like this, especially when describing her life today—life after "the dude," as she calls Castro, and the nearly 4,000 days she spent trapped in his grotesque prison of abuse.

From concentration camps to war experiences, history proves that people can survive unspeakable traumas. Yet there is no neat and tidy explanation as to how they do it. "Core elements are keeping hope up in some way: thinking about the future, and having something to occupy your mind so you're not dwelling on it all the time," says David Finkelhor, director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire. Some captives learn to dissociate or minimize what they're going through. "Some of the defense mechanisms that are occasioned by trauma may help victims get through really horrific experiences," says Dorchen Leidholdt, director of the Center for Battered Women's Legal Services at Sanctuary for Families in New York. "But when they get out it can make it harder for them to heal and rebuild their lives."

Culturally, we are fascinated by these modern-day Brothers Grimm fairy tales—the details of capture, the sadistic acts of violence, the complete and utter subjugation. But we are largely uninterested in their aftermath. Recovery, which presents a deluge of challenges (post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, substance abuse, chronic health conditions, abusive relationships and subsequent victimization), is far less uplifting than rescue, justice and restoring order to the world. "We want to believe that stories of kidnapping and captivity end, like the Disney version of Rapunzel, happily ever after," says Bruce Shapiro, executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. "But life after captivity can be harrowing too. We don't really want to know about that, because in a way, that's more frightening."

There is a cohort of women who know exactly how terrifying recovery can be. They are members of a society they never wanted to join, because membership meant enduring harrowing traumas and surviving to tell their stories. The names evoke some of the most hideous captivity tales on record. There's Jaycee Dugard, who, in 1991, was abducted while walking to a bus stop in South Lake Tahoe, California. Convicted sex offender Phillip Garrido and his wife, Nancy, held 11-year-old Dugard for 18 years in a makeshift compound of sheds and tents behind their house, where Phillip repeatedly raped Dugard and where she gave birth to two children.

Elizabeth Smart was 14 when, in 2002, Brian David Mitchell plucked her from her bedroom in Salt Lake City and kept her for nine months at a nearby campsite, raping her daily. In Austria, Natascha Kampusch spent eight years of her childhood imprisoned in a cellar. For 24 years, Elisabeth Fritzl's father stashed her in a basement dungeon, where he raped her and fathered seven children. And then there's Knight, whose torture was so brutal that, as Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Timothy McGinty puts it, "no one went through what [she] went through, barring the Korean or Vietnam prisoners, and they didn't go through it as long."

These stories are so darkly fascinating that many have been adapted into books, movies and TV shows. A Lifetime Original Movie, Cleveland Abduction, based on Knight's story, aired in May. The two other women Castro abducted, Amanda Berry and Gina DeJesus, co-authored Hope: A Memoir of Survival in Cleveland. Smart wrote My Story. Dugard penned A Stolen Life: A Memoir. All four books became New York Times best-sellers. Kampusch recounted her ordeal in 3,096 Days in Captivity, and she, Smart and Dugard were also the subjects of TV movies and films.

Hollywood loves to glamorize torture and sexual violence, from ripped-from-the-headlines tales to the 1991 thriller The Silence of the Lambs, about an FBI trainee (Jodie Foster) interviewing a brilliant psychiatrist turned cannibalistic psychopath, and Liam Neeson hunting down sex traffickers in Taken. And that makes it even harder to identify with real-life survivors of real-life cases. Perhaps for good reason: "None of us wants to imagine ourselves as that vulnerable," Shapiro says. " We say, 'They must have been implicated in their captivity in some way.' Or we focus for five minutes on the sensational details and the trial and then stop thinking about it."

It's a lot easier to focus on women like Knight when they're rescued—when their futures are filled with opportunity—than a few years later, when the sparkling promise of being saved may have given way to personal or professional struggles, or depression, or worse.

Recovery for the victims of these monsters is a lifelong maze, sometimes without a very bright light at the end. Survivors like Knight rarely have the chance to talk to someone who truly understands—from personal experience—the extended, twisted degradation they endured. Some are left dangling from a precipice that we'd rather not help them scale, either because we simply don't know how to or because it's easier to pretend they aren't dangling at all.

Sleeping in a Blue Garbage Can

Before Knight wandered into that Family Dollar store and accepted a ride from Castro, she had already survived a childhood mired in hardships. She grew up in a frenetic haze of poverty and filth, where school was an afterthought, soap and toothpaste were luxuries, and Pop-Tarts and SpaghettiOs were as nutritious as things got. She and her younger twin brothers, Eddie and Freddie, spent about a year living in a brown station wagon, and when their parents—who she says rarely held steady jobs—finally moved the family into a house, it was in a neighborhood crawling with prostitutes and drug dealers. They moved often, and with each new home came a revolving door of relatives, roommates and strangers.

"I have very few happy memories of my childhood," Knight says. She goes silent, as if searching for something she even wants to remember. "Playing with my brothers. Running around. Tag was our favorite game."

In school, Knight was teased incessantly, but life at home was worse: A male family member started molesting her when she was 5 years old, and the abuse escalated over the years from a couple of times a week to almost daily. "It's like I was buried six feet under and screaming and nobody can hear a thing," she says.

Knight ran away when she was 15. She slept in a blue garbage can beneath an underpass until she fell in with a marijuana dealer who traded her a room for her work as a drug runner. "I didn't think about what was gonna happen to me out there—how I could get killed or raped again. I thought, This is my way out."

Yet Knight was never very far from home. When a neighbor spotted her and told her father, he dragged her back to their house. The very next night, the same family member raped her again.

Knight passed into ninth grade but hated everything about school: The kids were mean, she was failing her classes, and she constantly felt "stupid." In her sophomore year, she got pregnant by a guy at school. She never told him, nor did she consider having an abortion. "Having my son was one of my happiest memories in my life," she says of Joey, who was born in October 1999. "Just seeing his little 10 fingers and toes, and seeing how beautiful he was. He's a gift."

When the boyfriend of Knight's mother broke Joey's leg, Knight watched helplessly as social services took away the one good thing in her life. She was 21. She didn't have a job or a car. She'd dropped out of high school. She was being molested at home and had no family support. How would she ever get her son back? "It's still a little difficult to talk about, even though it happened a ways back," she whispers. "The day that I disappeared, I didn't know that I was gonna be spending 11 years in a house full of torture, hell, chained up to poles, hanged from ceilings. I didn't know any of this was gonna happen. I was walking to go get my son back."

Raped Six Times a Day

Knight hung between those two poles in the pink bedroom for about a month. Castro would come home from work, lower her onto the floor, rape and beat her, and then, "Shoooo! Right back up," she says. "Oh my God, I felt so nasty. I felt sticky. I burned. I itched. I couldn't scratch. I was crying repeatedly. I was numb. I felt in so much pain."

One day, Castro dragged her into the basement, a stinking hovel of junk, clothes and boxes. He sat her on the floor, stuck another sock in her mouth and wrapped rusted chains around her neck and stomach, securing her body against a pole. Then he shoved a motorcycle helmet on her head.

"Let me see if I can give you an image," Knight tells me, lowering herself onto the floor. We're now sitting in a conference room at her lawyer's office, and she pulls a chair up against the left side of her body and tells me to pretend it's a speaker. There is a pole behind her, she says, then tilts her head backward and to the left into a position I can't imagine holding for more than a few minutes. "This is how my body was. I kept passing in and out because being like that and having a chain and motorcycle helmet on your head, you couldn't breathe, and if you did breathe, you had to breathe shallow."

Castro gave Knight a bucket to use as a toilet and tossed paper napkins at her when she had her period. Once a day, he brought her food from McDonald's. Eventually, he moved her to a bedroom on the second floor, where he took away her clothes and left her to freeze on a soiled mattress for months. He did not permit her to shower until after eight months of captivity. He brought her a puppy, but a few months later, he broke its neck in front of her. And he raped her again and again, sometimes six or seven times a day. Knight got pregnant five times during her 11 years in the house; Castro punched and starved her until she miscarried each one.

"I couldn't emphasize enough how much pain it was. And how every day was pure torture: what he did, how he did it or where he did it," Knight says. "It was hard to control my fear 'cause every day I thought I was gonna die. And if I didn't die, I was gonna be in pain."

The smallest luxuries became Knight's lifeline—green Dawn dishwashing liquid, which she used to brush her teeth, and the notebooks and pencils Castro brought her, which she used as a diary and sketch pad. When he put a radio and small TV in her bedroom, she finally caught up on the world: Michael Jackson suspended his baby over a balcony! Kelly Clarkson became the first winner on American Idol! Elizabeth Smart was found alive!

In April 2003, Knight was watching TV when she saw a report about a local Cleveland girl named Amanda Berry. She was 16 years old, and she'd gone missing. Soon after, Knight heard Castro blasting loud music from the basement. She had a dreaded hunch: He had someone else trapped down there, and it was probably Berry.

The first time she saw Berry was when Castro brought her into the pink bedroom and declared, "This is my brother's girlfriend." Knight remembers locking eyes with Berry and trading silent, terrified looks. For months after that, the two young women rarely saw each other. But Knight sensed that Castro preferred Berry—he let her sleep in the bigger room, gave her the color TV and permitted her to wear clothes while Knight went naked.

A year later, 14-year-old Gina DeJesus arrived. Castro chained her and Knight together in a second-floor bedroom. Sometimes he'd rape one of them on one side of the bed while the other one lay there, helpless. "Just to see it happen right in front of you, it's like, Damn, what am I gonna do?" Knight says. "The only thing in my head is, I grab her hand to say, 'Everything's gonna be all right.'" Knight sometimes begged Castro to rape her instead of DeJesus.

Year after year, Castro's hideous abuse continued. He let Berry and DeJesus watch news coverage of the vigils their families held, and told Knight no one was looking for her. He forced Knight to eat a hot dog smothered in mustard, fully aware that she was fiercely allergic to the condiment and pregnant for the fifth time. All the while, he played bass in a local band and entertained friends at his house. Early on in her captivity, when Knight was still chained up in the basement with that helmet over her head, she heard a handful of men talking in Spanish upstairs. Then there was music and singing. "Even if I could have let out a scream from under that helmet, there was no way any of those guys could hear me. The music was way too loud, and I was too far away from them," she wrote in her memoir. "As best as I could tell, those guys came over just about every Saturday." Yet no one—not neighbors, police or even Castro's own family—had a clue about the evil universe he'd painstakingly built inside.

Knight did anything she could to make it to the next day. She wrote poetry and drew pictures, dreamed of Arby's fries with hot sauce and constantly thought about her Joey. DeJesus, too, became a reason to live. "We used to sit there and, when he leaves [the house], just blast the music and try to make the best of it by singing, dancing, trying to do something halfway.... Something we know everybody else is doing," Knight says of the years she spent trapped in a room with DeJesus. "Adele's 'Skyfall'—me and Gina used to sing it when we were down and out, how we were gonna stick together and see through it all."

On Christmas Day in 2006, Castro took a fourth captive: his daughter. Berry gave birth to a baby girl in a plastic kiddie pool Castro placed on a mattress. He forced Knight to help with the delivery, telling her, "If this baby doesn't come out alive, I'm going to kill you." When the newborn turned blue, Knight performed mouth-to-mouth resuscitation until she started breathing again. Then Castro forced her to help dispose of the blood.

Berry's daughter, Jocelyn, became the darling of the house—a reason for the three captives to survive. Castro gradually loosened his rules. He nicknamed Jocelyn "Pretty," let her roam around the house and occasionally took her to local parks and even to church. As the years went by, he brought home children's books, Barney flash cards and toys. When Jocelyn got old enough to question the "bracelets" her mother wore, he stopped locking up Berry with chains. Eventually, he did the same for Knight and DeJesus.

'Daddy's Gone!'

On May 6, 2013, Knight woke up hungry and bored, fearing, as always, whatever Castro had in store for her that day. She and DeJesus were sitting in their room. Knight started sketching roses in her notebook. At some point, they turned on the radio, and she remembers hearing Nickelback's "Someday":

How the hell'd we wind up like this?

Why weren't we able

To see the signs that we missed

Try and turn the tables?

(In the memoir DeJesus wrote with Berry, DeJesus recalls that she and Knight were watching a Hilary Duff movie on TV. But Knight told me that she remembered their TV was broken at the time. This contradiction is not at all surprising; experts say trauma survivors will remember some parts of their ordeal in extraordinary detail yet have no recollection of other aspects of what happened to them. For the purposes of this article, I have followed Knight's account.)

Suddenly, they heard Jocelyn's little feet pitter-patter upstairs and into Berry's room. "Daddy's gone! Daddy's gone!" she shouted.

"In my head I'm saying, 'Yeah right, another test,'" Knight says, referring to the countless times Castro left the women unchained or unlocked their doors, only to be lurking in another room, waiting to pounce if they tried to escape.

Next, Knight heard Berry's bedroom door swing open and feet shuffling downstairs. About 15 minutes later, there were pounding and kicking noises from the first floor. "We either thought we were being broken into or [Berry and Castro] got into a fight," Knight says. "Then we hear, 'Police! Police!' I told Gina that anybody could say police. You never know. So we're just sittin' there. I tell her to go hide. I'll go check. At first I didn't know the door was unlocked at all. I turned it. I was like, 'Gina, door's unlocked, dude!' I closed it again 'cause I got scared."

Knight and DeJesus had no idea that after Jocelyn ran upstairs shouting "Daddy's gone! Daddy's gone!," Berry went down to investigate. She discovered that Castro had left the house and forgotten to bolt one of the doors. She opened it, only to find the storm door locked. She screamed until a neighbor helped her kick a hole in the bottom big enough for her and Jocelyn, then 6 years old, to squeeze out. They ran to a nearby house and called 911: "Hello, police? Help me! I'm Amanda Berry!" she said. "I've been kidnapped and I've been missing for 10 years and I'm here; I'm free now!"

But while waiting in her bedroom prison, Knight couldn't help but wonder whether the voices and noises they heard were part of yet another one of Castro's elaborate tricks. Then Knight saw a real, live police officer walking toward her. She hurled herself into his arms. "I literally felt like I was choking him, like I was hugging the life out of him," she says. "He hands me off to the other officer, and that's when, at the time, Gina was still in the bedroom. I was like, 'Gina, Gina, we're going home!'"

Knight followed the officer downstairs. When she stepped outside, the sun was so bright it burned her eyes. She looked down at what she was wearing—a grimy white T-shirt and a pair of dark pants Castro had found at a yard sale—and felt embarrassed. She was also nauseated and dizzy, and her chest hurt. "Then I felt a cold breeze coming through my nasty, dirty hair. And then I was like, This is real."

'Your Hell Is Just Beginning'

It had been 11 years since anyone had seen Knight alive, 10 for Berry and nine for DeJesus, and their improbable rescue captured the attention of the entire world. "We were in a state of shock for a long time," says McGinty, the county prosecutor. "We couldn't believe it, that they were under our noses—right there!" Berry's and DeJesus's disappearances received airtime on The Oprah Winfrey Show and The Montel Williams Show, inspired heartfelt vigils and led to police task forces. When the two women were released from the hospital, journalists and photographers flocked to their homes and recorded every balloon, stuffed animal and cheer from the crowd.

"The sad part is, no one was looking for Michelle," McGinty says. While Knight had been reported missing in 2002, the Cleveland police removed her missing person entry from an FBI database 15 months later. For the 11 years she was abducted, her case received hardly any publicity. Knight's grandmother, Deborah, told The Plain Dealer that the family assumed she'd run away after losing custody of Joey, but after Knight was rescued, her mother, Barbara, said she'd hung fliers around the city after her daughter disappeared and continued searching even after the police gave up. Barbara, who moved to Florida during Knight's captivity, also painted a very different picture of Michelle's childhood, claiming her daughter helped her grow a vegetable garden and loved doting on puppies and feeding apples to a neighbor's pony.

To all of this, Michelle says, "My mother all the time came up with fake stories." She alleges that Barbara kept her home from school, prohibited her from having friends and forced her to stay inside, all so she could collect Supplemental Security Income. "She made sure that I was dumber than a doorknob just to get the SSI money. But I'm not dumb," Knight said on the Dr. Phil show.

McGinty backs up Michelle's claims. "[Her mother] was getting Social Security money for disabilities, and all those years they forgot to tell the federal government Michelle was missing. They forgot all about her and moved to Florida and were riding her like a pension," he says. "She didn't spend much time protecting her child. The only reason I didn't prosecute her was...it would have traumatized Michelle more."

Castro pleaded guilty to 937 criminal counts, including kidnapping, rape and aggravated murder, and was sentenced to life in prison without parole, plus 1,000 years. Knight was the only survivor who chose to speak at his sentencing hearing. Wearing a gray and black dress and wire-frame glasses, she walked past Castro to the front of the courtroom, brushed back her bangs and said, "I spent 11 years in hell, and now your hell is just beginning. I will overcome all this that happened, but you will face hell for eternity." To this day, she has yet to see Joey, who was adopted by a family during Knight's captivity; his adoptive parents have sent Knight photos, but they feel he's too young to know the truth about her.

A month after his sentencing, Castro was found dead in his cell, hanging from his bedsheet with his pants and underwear around his ankles. It was ruled a suicide, and McGinty told the press, "This man couldn't take, for even a month, a small portion of what he had dished out for more than a decade."

'Nobody Was Lookin' for Me Either'

Knight cradles an iPhone in her hands as if it's a wounded bird. "Hello!" she says at the screen. "How are you?"

Smiling back at her is Elaine Cagle. She's 48 years old, lives in Wilmington, North Carolina, and her dirty blond hair falls loosely around her shoulders. For years, she has followed Knight's story from afar, not out of detached fascination but because she, too, survived more than a decade of trauma. This is their first time "meeting."

"I'm...good," Cagle says tentatively. For a moment, neither of them speaks. Then Cagle finds her words: "I actually found out about you when you first was taken," she says. "That's when my heart broke, because after going through what I went through, my mind just raced. Because I knew what I had been through, and I knew that"—she pauses—"nobody was lookin' for me either. And whenever"—she pauses again—"you were found, I was like, 'Well, thank God.' So, anyway..." Her voice tightens. "I didn't read your book, I'm really sorry, because I couldn't bring myself to do it."

"That's OK, sweetie," Knight says.

"But I did watch your movie," Cagle says, referring to Lifetime's Cleveland Abduction. "It was really hard. I really did feel the connection."

"Take a breath," Knight says, nervously giggling.

"About me, what happened to me. Is this what you wanna know?"

"Yeah," Knight says quietly.

Cagle takes a deep breath, blinks and begins: "When I was 3, I watched…a man"—she stops and looks away from the screen—"murder my father. And then I was placed in a foster home, and I was there for almost 10 years, where I was tortured mentally and physically, and sexually abused, and used as a slave. My foster parents' brother was, um, he, um, sexually abused me for almost 10 years. And at night they would lock me in a room and make me use the bucket under the bed [as a toilet]. And they would use a razor strap and beat me. And a horsewhip. And they would wake me up in the morning, and with a wire coat hanger they beat me on the feet. They told me that whenever I came of age, I was gonna marry this guy. It was crazy. It was torture every single day."

"Oh my God," Knight whispers.

"There was a whole lot more to it, but that's the reason why I could so relate to you," Cagle says. "Because then they tied me to a tree and beat me and left me there for days. They ended up putting me somewhere else where I was even more abused. So..." She lets out what sounds like a lifetime of pent-up air.

Knight stares at the screen, fighting back tears.

I first spoke with Cagle in March 2015, and in May, after a handful of hourlong telephone interviews, I asked whether she'd be interested in meeting Knight. She went silent. Through the phone, I heard a sniffle and a sigh: "That sounds great!" she said. "I would really like to talk to her." Cagle knew all about Knight's ordeal. She'd followed the news over the years, read about the rescue and watched some of her TV appearances. "Something struck me with Michelle more than the other ones [Berry and DeJesus]. I couldn't put my finger on why," Cagle says. "I think she has a lot of courage.... Probably a lot more than me."

Every minute in the U.S., 24 people are victims of rape, physical violence or stalking by an intimate partner. That's more than 12 million women and men a year—and these statistics lowball the problem, since many victims choose not to come forward. Some people, like Knight and Smart, gain a lot of public attention for surviving terrible things. But for every so-called famous survivor, there are many, many more who don't get any attention, yet they've experienced something equally awful. Cagle is one of these anonymous survivors. And like many with her background of abuse, she trusts few people with her story and has struggled to find a sisterhood of women who understand why it can be so hard operating in the real world after spending most of one's childhood surviving a nightmare.

"It can be very risky to tell your story to people around you," says Frank Ochberg, a pioneering psychiatrist and trauma expert who served as an expert witness for the prosecution in the Castro trial. "They don't believe you. Or they pity you. Or they get angry with you. When a person like Michelle or Elaine finds someone who is willing to listen and absorb it and appreciate it, it's important and it's unusual."

During our first interview, I asked Cagle about her childhood. "Have you ever seen Roots?" she asked. I nodded. "OK, well, that was it, that was me. [My foster parents] didn't want a child. They wanted slaves, and that's what we were." Cagle called her foster parents' house "the homestead," and said it didn't have running water, indoor plumbing or electricity. To get there, one had to walk a mile down a dirt road. Every day, Cagle said, she was forced to work in the tobacco fields, and every night she was either locked in her room or sent to her "uncle's" house, where he sexually abused her. She never had shoes and never saw a doctor.

"I have people say, 'Why didn't you just run away?'" Cagle tells Knight during their video chat. "I look at 'em and say, 'Run away where? We were in the custody of the state! They're just gonna take us right back to the situation where we were at. There was nowhere to run to.'"

Knight says, "I have a lot of people asking me the same question: 'Why didn't I escape from the house?' It's kinda hard when you're chained up!"

"Yeah and you've got someone cowering over you with a big whip, and you're in the middle of nowhere," Cagle says.

"Yes!" Knight says. "I can see where you come from, because even though the neighbors were so close, it was still difficult for us to get away. It's like, once we tried, we got knocked right back down."

"Yeah, that's the mind games," Cagle says. "Mmmmm. The mind games."

Knight tells her about the time Castro gave her a puppy and then killed it. "I thought it was a beginning to an end. Like, he was actually starting to be nice, but it was another one of his head games: 'I'm gonna give you something precious, and then I'm gonna rip it away from you just to watch you break.'"

Cagle replies with a story about how her foster parents locked her in an "old-timey wardrobe" for hours at a time. "They would say, 'You're a heathen! Sit in there and think about what you've done wrong. And you better pray to God. By the time we unlock this wardrobe, you better figure out what you've done wrong.'"

"And you wouldn't have a clue," Knight says.

"I was a little child!" Cagle says. "I would sit in there and just be beside myself, just wondering, What did I do wrong?" Cagle is fighting back tears. "Then I would come out. 'Well, did you figure it out?' And if it wasn't right, they would beat me and tell me how horrible I was."

"It's kinda like my mom and my dad telling me that I was worthless, that I wouldn't amount to anything, that I wasn't beautiful," Knight says.

"Oh, yeah, I heard that every day too."

"Stuff happens in life that you can't control, but at least you know now that you've got control over your own life," Knight says. "Whatever you do to make it happy now means more than anything in the world."

Cagle listens, her eyes glistening.

"So how you feeling?" Knight asks, smiling.

Cagle lets loose a big, weepy sigh. "Well...I feel like I've basically emotionally puked all over you!"

"That's good! That's good!" Knight says, laughing. "You're feeling some type of feeling, and that's really good. This is the hardest part for a person that went through what we went through: We do not want to talk about it with a person that don't know nothing about it."

Cagle says she spent eight years living with her foster parents before she was moved to a children's home, then sent back to live with her mother. Life there wasn't much better. She says her mother left her alone with a man who forced her to play Russian roulette. "My mom had such a drug habit that she pimped me out!" According to Cagle, her mother and both foster parents are dead. In her 20s, Cagle put herself through college, earning a degree in basic law enforcement training at North Carolina's Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College and pursued careers as a volunteer firefighter with the West Buncombe Fire Department, phlebotomist at Mission Hospital in Asheville and deputy sheriff in the Buncombe County Sheriff's Office. She also briefly served in the Army Reserve. "I'm really crying on the inside. It's like, Dang. Jeez! I'm disabled now. I don't do anything. I've had so many health problems it isn't even funny," she says. After suffering a panic attack during her stint as a police officer, she was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. She also suffers from agoraphobia. Through it all, her wife, Deborah Cagle, has been a loving, supportive constant. They met 14 years ago, entered into a civil union in 2004 and legally married in 2010.

Knight, too, faces serious health problems, from nerve damage in her arm to chronically cold hands caused by bad blood flow and deteriorating eyesight. She'll likely never be able to have children. And she has yet to see Joey again. "As bad as Gina and Amanda had it, and they had it bad, when Michelle came out, she couldn't even be reunited with her own child. That's awful!" McGinty says. "Lawyers told her, 'You wanna fight, we'll put up a fight, we'll get visitation.' But she realized it would be too disruptive of that child's life.... That's the ultimate sacrifice to me. So her torture went on."

Knight wants to go back to school, but not just yet. First, she's taking an almost schizophrenic approach to her future and trying a little bit of everything: gardening, cooking, nesting at home, writing music. In May, she recorded her first single, "Survivor." She's been in therapy and, over the past two years, overcome her fears of ropes, chains and helmets. "I was even able to ride a motorcycle!" she says. She dedicates much of her time to helping other survivors. This year, she spoke at the Cleveland Rape Crisis Center, the Northeast Ohio Amber Alert Committee and the Purple Project Foster Care Youth Conference. (She earns a living through her public appearances, along with financial support from the Cleveland Courage Fund, which raised over $1.2 million to support Knight, DeJesus, Berry and her daughter.) On her Facebook page, Knight shares updates from her life and offers advice to other survivors of abuse.

"I love helping people and seeing the smile on their face even when they feel down," she tells Cagle. "It lets me know that I'm worth something.... People don't understand how our lives are and how we can contribute a lot and help people. They see us as a disease. Like a drug addict. They see us and they label us, and they don't realize we are just as human as everyone else."

"Thank you," Cagle says. "Thank you."

Knight turns and looks at me, her voice getting higher as she talks. "I want people to know that I'm not just a story they threw on TV. I'm a person that has real feelings, just like her, that wants to be heard and wants their story to be out there." She takes a deep breath, sniffles and looks back at Cagle, who's crying and smiling.

"They were raised by wolves," Ochberg says of Knight and Cagle. "But when a survivor has a sense that enough people understand that this did happen and that she has dignity and deserves honor rather than pity, anger or disbelief—when she finds enough people who can give her that kind of reflection—she can heal."